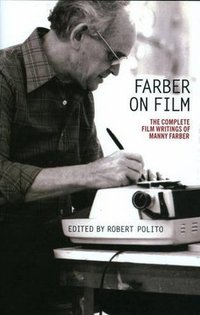

This month Library of America restores to print, via a new paperback edition, Farber on Film: The Collected Film Writings of Manny Farber, originally published in 2009. In connection with the book’s re-release, we now present the following interview with its editor, Robert Polito, which originally appeared as a downloadable PDF on loa.org in October 2009. Rich Kelley conducted the exclusive interview for Library of America’s e-Newsletter.

LOA: Manny Farber began reviewing films for The New Republic in 1942 and over the next 35 years had stints as a movie critic at The Nation, Esquire, The New Leader, Time, Artforum, Cavalier, and City. Spanning 824 pages, Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber collects all of his “film investigations” from these venues: hundreds of reviews and dozens of now famous essays. This is the third volume of film criticism published by The Library of America, after James Agee’s film criticism and American Movie Critics. What makes Manny Farber a canonical film critic?

Polito: Manny Farber is exactly right for The Library of America because he was not only a great film critic, but also ultimately a great writer comparable to the strongest poets and novelists of his generation. I can’t think of any other film critic, and few critics of any stripe, who compel as much for the originality and vitality of their prose as for their observations. Farber was the first American critic to render serious appreciations of B-movie and action directors—Howard Hawks, Samuel Fuller, William Wellman, Raoul Walsh, and Anthony Mann. But he was also among the first to focus on Rainer Werner Fassbinder, an early champion of Werner Herzog, and an exponent of such experimental directors as Michael Snow, George Kuchar, Andy Warhol, and Chantal Akerman. In a quip of J. Hoberman’s about Manny that I love, Farber “played both ends off against the middlebrow.”

LOA: In your introduction you call Farber “the most adventurous and original stylist of the midcentury El Dorado of American film criticism that spans Otis Ferguson, Robert Warshow, James Agee, Andrew Sarris, and Pauline Kael.” And later: “No other film critic has written so inventively and flexibly from inside the moment of a movie.” What is the Farber style?

Polito: Manny was one of the few critics of Modernism who himself wrote as a Modernist—his only peer in this regard, I think, is the D. H. Lawrence of Studies in Classic American Literature. Curiously, most critics of Modernist art, whether film, poetry, or painting, follow a belletristic essay tradition out of the European nineteenth and even eighteenth centuries. Farber instead employed a topographical prose—fragmentation, parody, allusions, multiple focus, and clashing dictions—to engage the formal spaces of the new films and art he admired. Puns, jokes, lists, snaky metaphors, and webs of allusions supplant arguments. Farber will wrench nouns into verbs (Hawks, he said, “landscapes action”), and sustains strings of divergent, perhaps irreconcilable adjectives such that praise can look inseparable from censure. Touch of Evil, he proposed, is “basically the best movie of Welles’s cruddy middle peak period.” For me, he arrives at a sort of startling poetry—his word and syntactical choices reminiscent perhaps of Robert Lowell, say, or Manny’s good friend Weldon Kees.

LOA: Farber on Film triples the amount of Farber’s writing in print. The only previous collection, Negative Space, was first published in 1971 and reprinted in an expanded edition in 1998. What new light does this much more comprehensive collection shed on Farber’s achievement?

Polito: When writers assemble collections of our writing, we tend to emphasize our latest work. Farber’s only prior book of criticism, Negative Space, perhaps inevitably accents his monumental performances of the late 1950s and 1960s: “The Gimp,” “Hard-Sell Cinema,” “Underground Films,” and “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art.” Negative Space collects, for instance, just a dozen full or partial film columns from The Nation (where he started reviewing in 1947, and published over 65 film pieces) and only a single film column from The New Republic (where he started reviewing in 1942, and published almost 175 film pieces). The wonder of these early reviews is how impressively his New Republic and Nation columns deliver both as traditional criticism and innovative Farber prose, as he elegantly addresses acting, plot, even entertainment value and annual best lists, aspects of movies his great essays resist. One of the pleasures of Farber on Film is tracking across three decades notions like “Termite Art” or “the gimp,” “negative space” or the “underground.” Just as notably, Farber on Film represents all the late film writing, particularly those created in collaboration with his wife, Patricia Patterson, starting with the Artforum columns in 1967 and running through the final City and Film Comment pieces of the 1970s.

LOA: In a 1977 Film Comment interview Richard Thompson asked Farber about the role of evaluation in his critical work. Farber dismissed it as “practically worthless. The last thing I want to know is whether you like it or not. . . . Criticism has nothing to do with hierarchies.” Sometimes it seems that Farber changes his opinion halfway through a sentence. His lengthy review of Taxi Driver is filled with lines like “Taxi Driver is a half-half movie: half of it is a skimpy story with muddled motivation about the way an undereducated misfit would act, and the other half is a clever, confusing, hypnotic sell.” Why was he so adamant about not going the “thumbs up, thumbs down” or Top Ten route?

Polito: Writing in Cavalier in 1966, Farber lamented that for most popular arts criticism, “Every review tends to be a monolithic putdown or rave.” Right from the start, his art and film columns shaped a sort of instructive anthology of the infinite ways of staging a mixed review. In his paintings, as well as in his writing, Farber would always demand multiple perspectives. Actually, in his inaugural review for The New Republic on February 2, 1942, Farber was already insisting on a multiplicity of expression and form, criticizing a Museum of Modern Art exhibition where each artist “has his one particular response to experience, and no matter what the situation, he has one means of conceiving it on canvas … Which is all in the way of making a plea for more flexibility in painting and less dogma.” As we were saying earlier, Farber was more interested in writing from inside the moment of a movie, and focusing those moments in his writing. His reviews are full of reversals and inversions—he’s always flipping over what he just said, always tracking another angle, another route.

LOA: Farber’s most influential essay is arguably “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” (1962), in which he lambasts “masterpiece art” that “blows up every situation and character like an affable inner tube with recognizable details and smarmy compassions” and hails “termite-tapewormfungus-moss art” that “goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and . . . leaving nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” Would you call this essay Farber’s critical credo?

Polito: Critical credo? Well, yes, and no. That’s obviously a beautiful and important essay, still a powerful vein of implication and resonance, endlessly re-applicable. You do see the dynamics of white elephant art in his reviews a full nine years before he wrote this essay. He connected elephantitis to films that would be dubbed noir (Laura and Double Indemnity), European films (Miracle in Milan), Japanese films (Rashomon), Oscar aspirants (Mrs. Miniver), and Disney cartoons (Bambi). And he personalized the white elephant/termite division in his introduction to Negative Space: “The primary reason for the two categories is that all directors I like . . . are in the termite range, and no one speaks about them for the qualities I like.” As termite artists he indicated a diversity of painters, writers, photographers, producers, and artists, which included Laurel and Hardy, Otis Ferguson, Walker Evans, sometimes James Agee, and film directors Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh, William Wellman, Samuel Fuller, Anthony Mann, and Preston Sturges.

Yet I believe Manny was too variegated and multiple in his approach to films to reduce him to a credo, any credo. If I had to privilege a single sentence it would be this, from the “Introduction” to Negative Space: “Most of what follows involves a struggle to remain faithful to the transitory, multisuggestive complication of a movie image and/or negative space.” Notice how nearly every word there moves in a different direction!

LOA: Farber’s essay “Underground Films” celebrated—and no doubt raised the profile of––many of the B-movie action directors of the 30s and 40s, yet in many of his reviews he questions whether the signature style we associate with a director or actor might have more to do with the cinematographer or the performance of some of the character actors. Can it be that Farber is both pre-auteur and anti-auteur?

Polito: Absolutely. So many of his most memorable pieces focus on a single director, Hawks, Sturges, Fuller, Huston, Fassbinder, Buñuel, Godard. But I recall that provocative conclusion of his 1966 essay, “The Subverters”: “One of the joys in moviegoing is worrying over the fact that what is referred to as Hawks might be Jules Furthman, that behind the Godard film is the looming shape of Raoul Coutard, and that, when people talk about Bogart’s ‘particularly American’ brand of scarred, sophisticated cynicism they are really talking about what Ida Lupino, Ward Bond, and even Stepin Fetchit provided in unmistakable scene-stealing moments.”

LOA: Susan Sontag called Farber “the liveliest, smartest, most original film critic this country ever produced. Maybe that’s because he wasn’t a film critic only but was—is––a wonderful painter. Farber’s mind and eye change the way you see.” Farber was a painter far longer than he was a critic. In fact, he stopped writing in 1977 to spend the next thirty years painting and teaching. Pauline Kael had a similar comment: “It’s his analysis of the film frame as if it were a painter’s canvas that’s a real contribution.” How did Farber’s painting inform his criticism?

Polito: Once you see his paintings after reading the film criticism—or alternately read his criticism after seeing the paintings—you realize they move along the same continuum. Much of Farber’s criticism precedes his important paintings, but some is contemporary with them. He could direct painterly thoughtfulness to such issues as color in Disney cartoons as far back as his first New Republic reviews, and always in his criticism references from film and art merge and blur. Still, the correspondences in Farber’s film criticism and his paintings are more radical and strategic. Just like his critical writing, his paintings are multifocused and decentered. Intense detailing arrests the eye amid chains of association, visual, cultural, or personal. They sometimes imply narratives, but without positing the entrances, exits, and arcs of any particular pre-existent story lines. Even in Farber’s earliest film criticism, as I suggest in my introductory essay, there is a prediction of the painter he would become. Along the way, certain reverenced film directors—Hawks, Wellman, Sturges, Lewton, Don Siegel, Jean-Luc Godard, Robert Bresson, Warhol, Fassbinder —will rise from the criticism almost as self-portraits of that future painter.

LOA: In 1966 Farber began collaborating in his writing with the painter and writer Patricia Patterson, who ten years later would become his wife. How did this collaboration affect his writing?

Polito: I hope someone writes a book about their collaboration, as Patricia was deeply involved in every aspect of Manny’s work, the painting as well as the writing, from the moment they met, and it’s a unique artistic situation, as far as I know. She’s of course a gifted artist on her own, so different from Manny in so many ways, and with her own retrospective coming up next year. Yet all his enduring art dates from after their meeting, and she totally enlarged the range of films he saw and they wrote about. Manny never struck me as nostalgic, and after they met he seems not to have looked back, only forward to the next work, the next writing, teaching, or painting, the next adventure. Patricia really extended Manny’s working world, and this permitted him to proceed along fresh routes while also consolidating what he had accomplished before, especially in the criticism, and the interplay between the criticism and the painting. His is a remarkable instance of self-reinvention in middle age, and I’ve marveled that Manny was so available to Patricia’s influence. He already had collaborated with another writer, W. S. Poster, on the big Sturges piece, and even his own criticism long before he started to collaborate with Patricia managed to insinuate a sense of multiple perspectives, even multiple voices into his prose—his New Republic and Nation columns often found him so thoroughly mixed as to suggest (at least) a pair of contrary authors. This is how they talked about the collaboration in a 1977 interview in Film Comment with Rick Thompson that we excerpt in the notes [p. 791]:

Manny Farber: Patricia’s got a photographic ear; she remembers conversation from a movie. She is a fierce anti-solutions person, against identifying a movie as one single thing, period. She is also an antagonist of value judgments. What does she replace it with? Relating a movie to other sources, getting the plot, the idea behind the movie—getting the abstract idea out of it. She brings that into the writing and takes the assertiveness out. In her criticism, she’s sort of undergroomed and unsophisticated in one sense, yet the way she sees any work is fulldimension—what its quality is rather than what it attains or what its excellence is; she doesn’t see things in terms of excellence. She has perfect parlance; I’ve never heard her say a clumsy or discordant thing. She talks an incredible line. She also writes it. She does a lot of writing in her artwork; she gets the sound related to the actuality in the right posture. It’s very Irish. You don’t feel there’s any padding or aestheticism going on, just the word for the thing or the sentence for the action. I’m almost the opposite of all those qualities: I’m very judgmental, I use a lot of words, I’m very aesthetic-minded, analytic.

Patricia Patterson: If it were up to me I’d never dream of publishing anything—it always seems like work in progress, rough draft. But he’ll say, “Just leave it at that.” I’m more practical than he is. Manny is willing to stay up all night long, take an hour’s nap, and then do another rewrite, retype, collage. He’s the workhorse of the pair of us; he does the typing. He will initiate many, many rewrites, come up with new tacks to explore when we’re way beyond deadline and patience.

Isn’t that fascinating? A sort of Sturges/Beckett dialogue about a mysterious process. Of course every partnership holds mysteries, but that sense of mystery is deepened here no doubt by the realization that they were specifically engaged in collaborative criticism, almost always a solo act. I’ve seen photos that show them totally absorbed at a desk, Patricia seated, Manny standing, an electric typewriter beside them, drafts everywhere, and they are the rare writer photos where the writers actually appear to be writing.

LOA: Was it Farber’s painterly sensibility or his predilection for termite-fungus-moss artists that made him the American critic most attuned and receptive to Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Snow, the New German Cinema, and Martin Scorsese when they first appeared in the 1960s and 1970s?

Polito: Over and over, one of Manny’s basic moves as a critic is to say something like, movies as we know them are finished, over…(Pause)…So let’s try to look at and describe what’s now here in front of us. He started that as far back as the early 40s—the way those films of the 40s proved so different from the silent films and pre-Code talkies he grew up on; but he kept doing it into the 60s and 70s, and even after, in his film classes at UC San Diego.

LOA: In his review of Negative Space in The New York Review of Books Sanford Schwartz painted a curiously contrarian portrait of Manny Farber, “In a career as a movie critic that lasted over three decades, he refreshingly, humorously, weirdly, and perceptively cut against nearly all our usual expectations of movies, asking us not to take seriously directors with highly personal styles, not to connect deeply with the allure of movie stars, above all not to think of movies as ‘art.’” Donald Phelps makes a similar point in his essay “Critic Going Everywhere”: “What really, valuably alarms about his writing is not its negativism but its wildness, its seemingly utter lack of commitment to any ideological post or political stand.” Farber never wrote in the first person, but wasn’t his personality very much part of his style? How wild could he get?

Polito: I sent the book recently to the poet Frank Bidart, and he called me right back, and we read some of our favorite passages to each other over the phone. Among other moments, Frank focused on Farber’s 1952 Nation review [p. 400], which opens this way:

“Clash by Night,” a passable movie about sexual unrest on Cannery Row, is like a blues number given class by a Stokowski arrangement and a hundred-piece symphony orchestra. Barbara Stanwyck returns to her clapboard homestead near a sardine cannery after ten years of romantic misery in the city. Working around San Something, California, are Paul Douglas, a dumb fisherman whom Stanwyck decides to marry for security, and Robert Ryan, a movie projectionist who not only speaks in the hard, poetic language of Stanwyck but has the kind of left-handed charm that causes the lady to stay up nights gazing at the most costly sky-and-sea shots ever to grace a Howard Hughes-RKO production…

Later in the review, Farber adds, “Stanwyck has occasionally been thawed out—by Sturges and Wilder—but here she is up to her old trick of impersonating a mentholated icicle.” The piece is still early Farber, but who else writes about movies this way? Moving in and out of the film, from action into topography, alert to space, gesture, and life as well as movie cliché—and also just so funny: that San Something, California; or “the most costly sky-and-sea shots”; and not only “impersonating a mentholated icicle” but “her old trick of impersonating a mentholated icicle.” I actually love Barbara Stanwyck, but here is stunning observation and writing . . . totally “wild,” as you say.

LOA: There are moments when Farber seems to be writing about something much larger than the film or filmmaker at hand. In his essay on Preston Sturges, for instance, he writes “The foibles of a millionaire, the ugliness of a frump . . . exist in themselves only for a moment and function chiefly as bits in the tumultuous design of the whole. Yet this design offers a truer equivalent of American society than can be supplied by any realism or satire that cannot cope with the tongue-in-cheek self-consciousness and irreverence toward its own fluctuating institutions that is the very hallmark of American society—that befuddles foreign observers and makes American mores well-nigh impervious to any kind of satire” [p. 463]. Isn’t this more like de Tocqueville?

Polito: I really like that notion of Manny Farber as a modern de Tocqueville—but he’s only part de Tocqueville, and maybe also part the Melville of The Confidence Man, isn’t he? Landscape, character, space, and language all bound up together…

LOA: When did you first discover Manny Farber’s work, and how has it influenced you?

Polito: I first met Manny over the phone, in the spring of 1999. I was a visiting poet for a semester at Berkeley, having lunch with Tom Luddy at Chez Panisse, and he asked me if I knew Manny. He pulled out his cell phone, as he often will, and suddenly there I was talking to Manny Farber. By the next week I was on a plane to visit him and Patricia. I feel Manny and Patricia taught me how to look—really see. My wife and I went on a museum trip with them to Washington, DC, and it was so instructive and thrilling to stand beside them in front of a painting as they talked about and sometimes even sketched what they saw.

LOA: Why did you decide to include excerpts but not all of the 1977 Film Comment interview with Patterson and Farber, which appears in full in Negative Space?

Polito: That’s a truly extraordinary interview, a dazzling, far-ranging performance on many subjects, passionately and elegantly phrased, and we include substantial excerpts, particularly as Manny and Patricia describe their collaboration on the film criticism and focus their critical principles. In that interview, and other interviews, Manny reflected on his own processes as a painter and critic with acute candor, and a lot of the information and background there was absorbed into the endnotes, the biographical timeline, and even the introduction. I’m currently editing another book, a book of Manny Farber’s writings on topics other than film—I have all the pieces, I’m ordering them now, and that Film Comment interview, along with all or at least most of the other interviews Manny did, will also go into that. It’s a far shorter book—and the working title, after a sui generis essay Manny wrote about all-night radio talk-jocks for The American Mercury, is Seers for the Sleepless: Art, Music, Comics, Furniture, Dinnerware, and Other Writings.