By Michael Sragow

In this breakthrough film noir, John Huston renders Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled prose in brooding images that perfectly capture Hammett’s frank, disillusioned sensibility.

Few movies capture men and women living by their wits as keenly as John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon. Seventy-five years after Huston leapt from screenwriter to writer-director with this swift, charismatic adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, the interplay of hard-bitten private eye Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) with a trio of elegant con artists—breathless prevaricator Brigid O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), exotic connoisseur Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), and obese, diabolically articulate Kasper Gutman (Sidney Greenstreet)—flashes like sheet lightning. As they spar for possession of the golden, jewel-encrusted falcon created by the Knights Templar of Malta during the Crusades to pay homage to the King of Spain, they keep each other and the audience guessing about their tactics, motives, and morality.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Dashiell Hammett: Complete Novels |

In this game of existential charades, played for blood and money, you must constantly guess who these characters really are. O’Shaughnessy sometimes goes by “Wonderly” and “LeBlanc,” Gutman is referred to as “G” or “The Fat Man,” and the falcon itself is “the black bird,” camouflaged in ebony enamel. Huston anchors the story (as did Hammett) in Spade’s tough-minded professionalism, which makes no concessions to legality, politesse, passion, or compassion. To Brigid he’s “wild and unpredictable,” to Kasper he’s “an amazing character.” And to them, why wouldn’t he be? Honor among these thieves is strictly negotiable, and the cops on their tail are no savvier or more competent than a hotel house detective, maybe less so. When the competitors and sometime conspirators finally have the falcon in their grasp (or so they think), and their play-acting and flimflam fall away, what’s left is a remarkable group portrait of greed.

Yet the movie is no screed against avarice, but a dense, vivid tapestry of men and women zigging and zagging through an urban dream world. Its vision of San Francisco, created on the Warners lot and with stock footage, helped to define the ambiance of film noir, our great iconoclastic urban crime genre—Hollywood’s image-smashing alternative to mom-and-apple-pie Americana. Civic pride, romantic ideals, marriage and other sentimental partnerships—all get upended in film noir. So does the time of day. Cops crowd in on Spade at his apartment in the wee small hours of the morning. The climactic scene is a long night’s journey into day. A film noir like The Maltese Falcon can affect you in an overpoweringly sensual way; it makes you react viscerally to artificial light. Huston and his ace cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, streak interior scenes with ominous shadows, like those of an elevator gate closing on a felon who banked on getting away with murder.

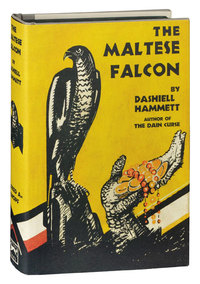

The reviews for Hammett’s novel, his third, were the best of his career. Gilbert Seldes, the trailblazing explorer of America’s popular arts, pooh-poohed the book’s mystery elements, but went on to declare that “everything else, character, plot, and the general attitude of the author, are fresh and novel and brilliant.” The reviews for Huston’s movie, the third screen version of the novel, were sensational. Near the end of his tenure, The New Republic’s Otis Ferguson, the most perceptive American film critic of the 1930s, hailed it as “the first crime melodrama with finish, speed, and bang to come along in what seems like ages.” Even The New York Times’s Bosley Crowther got it: he dubbed it “one of the most compelling nervous-laughter provokers yet.” Released without fanfare in New York, it became a smash there and across the country, as well a triple Academy Award nominee (for best picture, screenplay, and supporting actor—Greenstreet). A young moviegoer who said she had “enjoyed” Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane a few months earlier testified a few decades later, “I found more excitement in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon.” Her name is Pauline Kael.

Despite legions of imitators, the movie has retained its capacity to enthrall and startle audiences thanks to the peculiar meshing of Huston’s talent and personality with Hammett’s. The characters don’t always match Hammett’s descriptions—unlike the dark, compact Bogart, the book’s Spade is a tall fellow with an “almost conical” physique, who looks “rather pleasantly like a blonde Satan.” The movie, though, is strikingly faithful to Hammett’s dialogue, and to its rhythms. Bogart mastered Spade’s vocal defaults, “the steady, matter-of-fact voice that was devoid of emphasis or pauses.” And Huston hewed to Hammett’s structure and ignited his situations with pitch-perfect humor and intensity. Screenwriter turned writer-director Walter Hill (48 HRS., The Warriors), one of Huston’s later collaborators, told me, “No director had more reverence for the written word,” adding, “sometimes to his detriment”—a reference to their forgettable 1973 adaptation of Desmond Bagley’s The Mackintosh Man, but emphatically not to Huston’s Hammett. In Hill’s view, “In The Maltese Falcon and The Asphalt Jungle and most of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, he brought the terseness and toughness of the American hard-boiled style to the screen as well as anyone.” That’s partly because Huston understood this style as the expression of a frank, disillusioned sensibility.

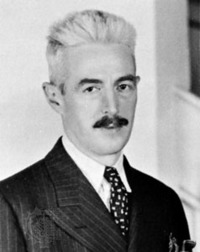

Few writers ever matriculated from a harsher school of hard knocks than Hammett. A high-school dropout, Hammett worked odd jobs to support his family and became an operative for the Pinkerton Agency when he was twenty-one. Serving stateside in a U.S. Army motor ambulance company during World War I, he contracted Spanish flu and then tuberculosis. The TB repeatedly stymied his return to detective work. He married a staff nurse (she was already pregnant with the first of their two daughters), struggled to make ends meet as a writer (drawing on his Pinkerton experience), then found fleeting security as a copywriter for a jeweler. High living and hard drinking caught up with him; a recurrence of TB and a bout of hepatitis kept him from steady work. He began writing fiction with new urgency, establishing himself as the biggest name in the roster of crime writers for Black Mask magazine, and then the star of Alfred A. Knopf’s Borzoi Mysteries line. “While Hammett’s reputation soared, his personal life deteriorated,” Richard Layman summarized when introducing Hammett’s Selected Letters. Hammett wrote his string of tough-guy suspense masterworks while in a constant state of turmoil.

You’d think there would be little overlap between Hammett, the son of a nurse and a failed clerk/salesman/foreman/bus conductor, and Huston, the son of a journalist, Rhea Gore, and the great actor Walter Huston (who does an uncredited cameo as poor doomed Captain Jacoby). But when John was born, Walter was a power-station manager, not a film and stage star, and the younger Huston confronted mortality at a younger age than Hammett did. When he was ten, doctors convinced his mother (after she and Walter had divorced) that John had both an enlarged heart and chronic nephritis. He revolted against being treated as an invalid. Huston would sneak out of bed at night and jump into the waters of a nearby canal. One evening the canal gates opened and sucked him through the locks. He felt as if he were shooting down rapids and a waterfall. Huston later told his co-scenarist on The African Queen, James Agee, “The first few times it scared the living hell out of me, but I realized—instinctively anyhow—it was exactly fear I had to get over.”

Huston, too, dropped out of high school. He boxed in California, acted in New York, and rode with the Mexican cavalry. His career came into focus when he wrote a puppet play based on “Frankie and Johnny” and two stories about fighters that he sold to H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury. (Mencken had also co-founded Black Mask.) Huston began screenwriting in Hollywood, sought in vain to break into the British film industry, suffered through an ill-fated first marriage (of five), attempted to paint in Paris, bummed around London, and eventually became a trusted scriptwriter at Warner Bros. in Burbank.

Huston got his shot at directing after penning a string of successful scripts, notably Gary Cooper’s Oscar-winner Sergeant York (directed by Howard Hawks) and an adaptation of W. R. Burnett’s High Sierra (directed by Raoul Walsh) that gave Bogart his best pre-Spade role as a Dillinger-like outlaw. An avid Hammett fan, Huston believed that two previous Maltese Falcon films had trashed the writer’s material. As a first step, he ordered his secretary to break down the novel in script form. When this preliminary exercise wound up on Jack Warner’s desk, the mogul gave it the green light. (Hammett himself thought his book could easily become a stage play.) In his final draft, Huston eliminated two minor characters (Gutman’s daughter and Spade’s attorney) and excised a digression that Hammett scholars consider crucial to the novel’s meaning. Spade tells O’Shaughnessy the story of a realtor named Flitcraft, who abruptly leaves his wife, children, and job after being grazed by a falling beam on a city sidewalk. Five years later he turns up in a different city in the same state, with an eerily similar family and comparable employment at an auto dealership, leading the same kind of level-headed middle-class life he did before. One of Hammett’s key appreciators, Steven Marcus, takes a singular moral from the story: even after men are shocked into recognizing the randomness of life and death, “they will persist in behaving and trying to behave sanely, rationally, sensibly, and responsibly.” But here’s what Spade actually says about Flitcraft: “He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.” Spade isn’t even sure that Flitcraft “knew he had settled back naturally into the same groove he dropped out of.” The story can be read as a parable about the persistence of personality, not the dominance of rationalism per se. And if Huston didn’t include it in the script, perhaps it’s because every other piece of the action demonstrates this concept. O’Shaughnessy will always hope that her feminine wiles will spring her from a jam, Gutman and Cairo will never give up on the falcon as their object of desire, and the most enigmatic of them all, Spade himself, will not relinquish his independence or “play the sap” for anyone, no matter how attached he gets to O’Shaughnessy or how enticed he is by Gutman’s quest.

The ability to figure out a puzzle on the fly is crucial for both gumshoes and directors, certainly one as peripatetic as Huston. By the time he took on The Maltese Falcon in 1941, Huston was ready for the challenge. Under his direction, everyone in front of and behind the camera (in particular, cinematographer Arthur Edeson) performs en pointe. No word or motion is wasted—even the crawl stating that pirates “seized the galley carrying this priceless token and the fate of the Maltese Falcon remains a mystery to this day” adds a note that reverberates after the climax. Bogart sets the tone for his wary, cagy, hyper-alert, and hands-on Spade from the moment we see him rolling a cigarette as his girl Friday, Effie Perine (Lee Patrick), announces a potential client, saying “she’s a knockout.” The femme fatale is O’Shaughnessy (Astor), though initially she calls herself “Wonderly.” She spins a tale about needing help to prevent her sister from running away with a married Brit, Floyd Thursby. Before long, Spade’s partner, Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan), enters, is immediately charmed, and volunteers to be the one who tails the Englishman. The audience doesn’t yet know that Spade is sleeping with Archer’s wife, Iva (Gladys George). But even as Spade and Archer share an unspoken, shrewd appraisal of Wonderly’s readiness to shell out two hundred dollars, Bogart injects a derisive edge into Spade’s attitude toward his partner: After Miles lays down his claim, saying, “Maybe you saw her first, but I spoke first,” Spade replies with a sardonic chuckle, “You’ve got brains, yes, you have.” The camera glides to the shadows on the floor spelling out “Spade and Archer” from the signage in the window. In the very next shot, Miles, on the job, appears stunned when an unseen killer raises a gun from the right corner of the frame and fires, spilling his dying body down a hill.

That kinetic vignette is the one scene that isn’t filmed from Spade’s perspective (the private eye is asleep in his apartment when it happens): the studio instructed Huston to shoot that bit. The director thought it violated his aesthetic game plan, but it works wonders for the movie. Filming the homicide from the murderer’s point of view fixes the movie’s ultimate question in the audience’s mind—not “What is the Maltese Falcon?” but “Who killed Miles Archer?” That puzzle is the one that compels two cops (Ward Bond and Barton MacLane) to hound Spade, more so after they discover his affair with Iva Archer. Later, it will resolve Spade’s romance with O’Shaughnessy. The black bird functions not as a mystery but as what Alfred Hitchcock called a MacGuffin, the object that drives the action. Of course, it’s one of the greatest MacGuffins in cinema, thanks to the merry-go-round of crooks that spins around it.

| BUY THE BOXED SET |

|

| Dashiell Hammett: The Library of America Collection (Two volumes) |

Hammett’s peer, Raymond Chandler, in his seminal essay “The Simple Art of Murder” (1944), famously wrote that Hammett “gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse.” At first glance, the dramatis personae of The Maltese Falcon are as flamboyant as any rogues gallery in an Agatha Christie whodunit, and their quest to find a legendary antique seems impossibly esoteric. But when he introduced the Modern Library edition in 1934, Hammett identified real-life counterparts to each supporting character. Cairo’s prototype was a forger, Gutman’s a suspected German secret agent; Brigid was a composite of an artist and “a woman who came to Pinkerton’s San Francisco office to hire an operative to discharge her housekeeper.” None had more specific roots than “Wilmer, the boy gun-man,” who was “a neat small smooth-faced quiet boy of perhaps twenty-one.” In the film, Elisha Cook, Jr., exuding a callow sort of bravado, is perfect as Wilmer, the recipient of Spade’s most penetrating putdown: “The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter.” Spade calls him a “gunsel”—a word that can mean “punk” and “passive homosexual.” Referring to Wilmer, Brigid tells Cairo, “you might be able to get around him, Joel, as you did the one in Istanbul.” Gutman keeps insisting that he loves Wilmer like a son. Anyone who thinks this movie scants Hammett’s sexual undertones isn’t paying attention.

Hammett divulged that unlike Wilmer and Cairo and the rest of the supporting players, “Spade had no original. He is a dream man in the sense that he is what most of the private detectives I worked with would like to have been and what quite a few of them in their cockier moments thought they approached. For your private detective does not—or did not ten years ago when he was my colleague—want to be an erudite solver of riddles in the Sherlock Holmes manner; he wants to be a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody he comes in contact with, whether criminal, innocent by-stander, or client.”

It’s this heady combination of fantasy and grit that makes Huston’s movie so elating and distinctive. He stylizes the compositions and engineers the intricate camera moves to put us behind Spade’s observant eyes, which take in almost every setup with a rapidity that throws his foes off-kilter. In a creative masterstroke, Huston built sets that had ceilings, frequently angling his shots from the floor. As he said in 1978, “There was a time there, after Orson Welles—and I’m partly to blame because of The Maltese Falcon—when everything was shot looking upward at the character.” Nothing in this film is random or affected. When Gutman, even seated, looms over Spade and the audience and seems to be squeezed into the frame, it communicates the force and danger of a criminal mastermind who might otherwise have come off comically or campy. Huston saw the British-born Greenstreet, a longtime Theatre Guild performer, at the Biltmore Theater in Los Angeles, when he was touring with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. The Maltese Falcon would be Greenstreet’s first film, but “he was perfect from the word go, the Fat Man inside out,” as Huston wrote in 1980. This novice at acting for the camera dares to go large, moving with outsize grace and confidence while sounding threatening notes with his rumbling lower register. The camera sometimes peers down on Peter Lorre’s Cairo, so often caricatured as screechingly effete, yet actually full of finesse and revelatory strokes of character, whether he’s fondling his cane while taking Spade’s measure or acting like a sad-faced clown, pretending to be a victim of police brutality. The Hungarian émigré Lorre had made his mark in movie history as the child murderer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and the child kidnapper in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), but he’d recently settled into a string of amiable B pictures as the Japanese detective Mr. Moto. Cairo served as Lorre’s comeback role and the first of nine team-ups with Greenstreet. (When Lorre costarred in Huston’s Beat the Devil a dozen years later, Greenstreet had retired from movies, and Robert Morley took his place as Huston’s favorite Fat Man.)

No one offers more sophisticated fun than Mary Astor as O’Shaughnessy, notably when she drops her “schoolgirl manner” and levels with Spade, eye to eye: “I’ve been bad. Worse than you could know.” Astor’s earlier choice roles were the adulterous newlywed in Victor Fleming’s Red Dust (1932) and the sympathetic divorcee in William Wyler’s Dodsworth (1936). She lobbied to play the woman of mystery after reading Huston’s script and declaring it “a humdinger.” In her first-rate memoir, A Life on Film (1971), she describes O’Shaughnessy as a “bitches’ cauldron.” Astor confesses, “I hyper-ventilated before going into most of the scenes. It gave me a heady feeling, of thinking at cross-purposes. For there wasn’t a single scene in the picture where what I said was even close to what I was thinking.” When Spade’s presence in her apartment discomfits O’Shaughnessy, she fiddles around the fireplace and lights a cigarette. Humor doesn’t get any drier than Spade witnessing Astor’s weird ballet and asking, “You’re not gonna go around the room straightening things and poking the fire again, are you?” (Astor won the best supporting actress Oscar that year for playing an icy concert pianist in The Great Lie, but she wrote, “If I’d had my druthers, I would have preferred getting my Oscar for Brigid.”)

Bogart is sure-footed and ingenious in this story’s close quarters. He simmers with banked rage and pulls off Spade’s jolting quick changes, from bantering bonhomie to fury when he feels the cops are crowding him, and from feigned rage to self-satisfaction after he puts on a show of anger for Gutman. The star embraces Spade’s mulish determination to stay independent and “not play the sap” for anybody. His diamond-hard performance and Huston’s stringent, witty direction imbue this film with modulated fierceness.

Whether as an influential film noir or a template for detective movies, The Maltese Falcon long ago entered the DNA of smart and savvy moviemakers. In an early draft of Chinatown (1974), for example, screenwriter Robert Towne’s cocky private eye, J. J. Gittes (Jack Nicholson), says, “In my case, being respectable would be bad for business”—an inadvertent riff on Spade saying “Don’t be too sure I’m as crooked as I’m supposed to be. That sort of reputation might be good business, bringing in high-priced jobs and making it easier to deal with the enemy.”

“In regard to that ‘bad for business’ quote,” Towne recently wrote me, “it doesn’t show up in the shooting script of Chinatown so I obviously removed it. I guess it was an unconscious echo that I didn’t feel was right for Gittes.” The parallels between Gittes and Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) and Spade and O’Shaughnessy go a bit deeper. Referring to O’Shaughnessy as an archetypal femme fatale, Towne says he consciously headed in the opposite direction: “Evelyn was the heroine of Chinatown.” Presenting her “as the traditional femme-fatale black widow” was, he hoped, a clever ploy, “concealing her decency and misleading the audience for a time, like any good detective movie should.”

Spade’s canny, ruthless—or by-the-book—treatment of O’Shaughnessy has divided some of our most celebrated critics along gender lines. Pauline Kael praises The Maltese Falcon for being true to Hammett’s Spade: “a loner who uses simple people, a man who is constantly testing himself, who doesn’t want to be touched, who enjoys hitting Joel Cairo and humiliating Wilmer, a man who’s obsessively anti-homosexual.” So when Kael voices “one regret,” it’s that “Huston didn’t (or couldn’t) retain Hammett’s final scene—when Effie realizes what a bastard Spade is.” But does that overstate the point? In Hammett’s last two pages, Effie does get shaken to her core when she reads the news that Spade sent O’Shaughnessy up the river. Spade reminds her “she did kill Miles, angel . . . offhand, like that,” as he snaps his fingers. And though Effie commands him not to touch her (“not now”), she admits, “I know you’re right.” In the book’s final line, Spade tells Effie to usher Archer’s widow Iva into his office. Does that, too, make him a bastard?

Or is Dwight Macdonald correct, writing in Esquire: “Sam Spade has what is generally called a ‘continental’ attitude toward women—he likes them but they aren’t all that much. He rates his own skin first (realism about death), money second (in a capitalist society, money is part of one’s skin), and sexual love third.” Mocking the way O’Shaughnessy “looks on with horrified incredulity” when Spade calls the police, Macdonald quips, “The poor woman has obviously seen too many movies.”

It’s a tribute to the vitality of Huston’s film that it can still inspire fresh arguments. Just last month, Roger Rosenblatt told The New York Times Book Review that the moral of The Maltese Falcon, which he named his favorite adaptation, is “that love doesn’t conquer all, and that the test of morality is doing what you least want to.” But that’s only a partial reading. What Spade actually tells O’Shaughnessy is that he won’t “play the sap” for her “because all of me wants to, regardless of consequences, and because you’ve counted on that with me, the same as you counted on that with all the others.” Spade is simply staying true to a morality that is based on self-preservation.

Huston’s Maltese Falcon towers over its successors—and its predecessors. Ten years ago, Warner Home Video released a two-DVD set bringing together all three movies of Hammett’s novel. Roy Del Ruth’s 1931 version, made during the freewheeling era before the Production Code got teeth, features a slick, satyr-like Spade (Ricardo Cortez) and a bathtub scene for Miss Wonderly (Bebe Daniels). But Cortez overdoes his lothario grin, Del Ruth’s storytelling is flaccid, and the coda is a travesty: Spade joins the D.A.’s office as a chief investigator and buys Wonderly some special treatment in prison. William Dieterle’s 1936 version, Satan Met a Lady, with Warren William and Bette Davis, is a conscious travesty, from beginning to end—a blatant (and bungled) attempt to turn The Maltese Falcon into the same kind of cheery franchise that MGM had skillfully established with Hammett’s larky The Thin Man. Satan Met a Lady is the movie equivalent of a trashy novelty number, complete with a female version of the Fat Man.

Before Hammett’s Selected Letters appeared in 2001, biographers reported that the author either despised Huston’s version or grew to like it grudgingly, over time. But in a letter dated “20 October 1941,” just two and a half weeks after its premiere, Hammett asked his daughter, Josephine: “Have you seen The Maltese Falcon yet? They made a pretty good picture of it this time, for a change.” Let’s allow the author to have the last word.

Official trailer for The Maltese Falcon (2:42)

The Maltese Falcon (1941). Directed and written by John Huston, from Dashiell Hammett’s novel. With Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sidney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, and Elisha Cook Jr.

Buy the DVD • Buy the Blu-ray • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Michael Sragow is the curator of Library of America’s Moviegoer feature. He is a Contributing Editor and online movie critic for Film Comment and author of Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master.