By Edmund N. Santurri

Professor of Religion and Philosophy, St. Olaf College

This past November, in an exchange with Library of America publisher Max Rudin, I mentioned incidentally that I was planning to assign the LOA’s Reinhold Niebuhr volume in my spring 2016 St. Olaf College course “Obama’s Theologian.” Max asked whether I might write an LOA blog post explaining “why the course, why the book, and [my] passion for Niebuhr.” Here goes.

Why the course?

In a well-known 2007 interview conducted by New York Times columnist David Brooks, then-presidential candidate Barack Obama revealed his admiration for the twentieth-century American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Since that interview and throughout Obama’s presidency, commentary on Niebuhr as “Obama’s theologian” has become a growth industry.

Those who think the Obama-Niebuhr association spot-on argue that Niebuhr’s vision of a “fallen” political world haunted by ideals compromised in concession to political reality—but a world also leavened by reasonable hope for redemptive moments that mitigate moral tragedy and curb Machiavellian temptations—is a vision that distinctively marks Obama’s career as politician and statesman. A commonly cited case in point is Obama’s 2009 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, which acknowledged the tragic necessity of waging war to combat real evil in the world, but which denied that this was “a call to cynicism.” In preparation for the speech, Obama’s advisors compiled a set of readings that included selections from Niebuhr’s works.

Other commentators challenge the Obama-Niebuhr association as misleading, wrongheaded, superficial, or overdrawn since Obama has sometimes embraced perspectives (e.g., classical just-war theory) that Niebuhr had criticized. Whatever one’s views on that matter, the assertion that Niebuhr’s “Christian realism” significantly explains Obama’s political outlook and practice turns out to be an engaging and pedagogically fruitful point of departure for college students encountering Niebuhr’s theology, ethics, and political thought for the first time.

Besides: to study Niebuhr is to study a writer who is arguably the most significant American Christian thinker of the twentieth century, a theologian whose influence extended well beyond theological circles. Onetime ambassador to the Soviet Union and renowned “political realist” George Kennan is reported to have said that Niebuhr “is the father of us all.”

Why the book?

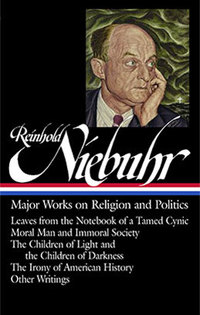

The LOA’s Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics is exceedingly useful for my course because it brings together for the first time in one volume four of Niebuhr’s most important works in their entirety: Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic (1929), Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932), The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (1944), and The Irony of American History (1952). These texts, along with another of Niebuhr’s greatest works, An Interpretation of Christian Ethics (1935), form the course’s intellectual infrastructure. But the LOA Niebuhr volume also includes a rich selection of extracts from other published works, sermons, lectures, prayers, and journalistic pieces written by Niebuhr in response to important political events from 1925 to 1967. Indeed, I think a strong case can be made that his occasional political essays show Niebuhr at his literary best, combining exquisite clarity, expressive economy, pungent rhetorical power, and profound theological substance. The political essays are also inviting and accessible, less formidable than the formal political and theological treatises—and thus especially useful for teaching purposes.

My passion for Niebuhr

For me the principal attraction of Niebuhr’s work is its anthropological vision. That vision is traditionally Pauline or Augustinian in casting the world as fallen, but it’s also one that Niebuhr imaginatively rearticulated in trenchant observations of signature twentieth-century political events. According to Niebuhr, human beings generally are confronted with two persistent temptations: (1) the temptation to overreach, to ignore human limits, to indulge in Messianic delusions—what Niebuhr calls the sin of pride, and (2) the temptation to underachieve, to surrender prematurely, to evade responsibility for action in the world—what Niebuhr calls the sin of sensuality. This condition marks international as well as personal relations:

Nations, as individuals, may be assailed by contradictory temptations. They may be tempted to flee the responsibilities of their power or refuse to develop their potentialities. But they may also refuse to recognize the limits of their possibilities and seek greater power than is given to mortals (page 561).

In different historical moments one or the other temptation may predominate. Thus, for Niebuhr, in March 1941 the principal American temptation was to avoid the “terrible ordeal” of a war against Hitler despite its moral necessity, a temptation buttressed by “delirious dreams of a health which is not in the realm of possibilities” (p. 624). In 1952, on the other hand, as it looked toward a protracted struggle with the Soviet Union, the United States faced the very real

temptation to become impatient and defiant of the slow and sometimes contradictory processes of history. We may be too secure in both our sense of power and our sense of virtue to be ready to engage in a patient chess game with the recalcitrant forces of historic destiny. We could bring calamity upon ourselves and the world by forgetting that even the most powerful nations and even the wisest planners of the future remain themselves creatures as well as creators of the historical process. (p. 561)

For Niebuhr, even when such temptations are resisted, final decisions are nonetheless filled with risk, uncertainty, moral ambiguity, and residual wrongdoing. “There is no escape from guilt in history. This is the religious fact that St. Paul understood so well and that is so frequently not understood by moralistic versions of the Christian faith” (p. 655). So Niebuhr wrote in defense of the allied bombing of German cities and civilians in World War II.

And here it is difficult not to think in association: Obama, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Syria, Russia, China, Al Qaeda, ISIS, drone warfare, non-combatant death, Guantanamo—the list goes on. About these and similar matters it’s hard not to feel as Niebuhr undoubtedly would have felt. The temptations are enormous. Even the best decisions carry the burdens of risk, uncertainty, moral ambiguity, and residual wrongdoing. And with Niebuhr it’s hard not to feel that if there is any redemption in our circumstances it is intimately tied to an attitude of profound humility fostered by a sense of reality beyond human making or control, a reality that judges yet forgives our inevitable mistakes and transgressions:

There is, in short, even in a conflict with a foe with whom we have little in common the possibility and necessity of living in a dimension of meaning in which the urgencies of the struggle are subordinated to a sense of awe before the vastness of the historical drama in which we are jointly involved; to a sense of modesty about the virtue, wisdom and power available to us for the resolution of its perplexities; to a sense of contrition about the common frailties and foibles which lie at the foundation of both the enemy’s demonry and our vanities; and to a sense of gratitude for the divine mercies which are promised to those who humble themselves. (p. 589)

Edmund N. Santurri is Professor of Religion and Philosophy at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota and member of the Advisory Committee for the college’s Institute for Freedom and Community. He also authored the Introduction to the recent Westminster John Knox Press reissue of Reinhold Niebuhr’s An Interpretation of Christian Ethics.