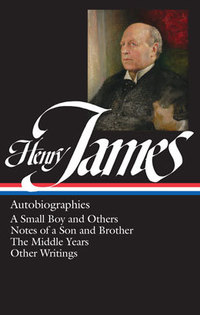

Library of America takes special pride in the release this week of Henry James: Autobiographies, a collection of three memoirs—A Small Boy and Others (1913), Notes of a Son and Brother (1914), and the unfinished The Middle Years, published posthumously in 1917—together with an assortment of his autobiographical essays and notebook entries and a fond reminiscence by Theodora Bosanquet, the secretary to whom James dictated all three works.

The sixteenth volume in LOA’s Henry James edition, Autobiographies is timed to the hundredth anniversary of his death on February 28, 1916.

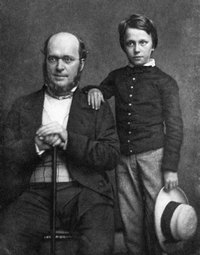

With the enormous growth of memoir as a literary genre in recent decades, it’s more than time for these lesser-known late works to find a new audience. But readers shouldn’t expect a linear recounting of a life story in these books. What James provides instead is something much less orthodox—a sensuous, almost stream-of-consciousness evocation of the sights, sounds, and smells of his childhood and adolescence, in locales that include Albany, Newport, and New York on one side of the Atlantic, and London, Paris, and Geneva on the other. (The detailed end notes by volume editor Philip Horne are a virtual Baedeker to this vanished nineteenth-century world.)

If there’s anything like a narrative through-line in the collection, it’s the growth of James’s famously developed aesthetic sense, for which any experience is fodder, from a bout with typhoid fever to a crude but vivid stage adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. (James refers to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel as “my first experiment in grown-up fiction. . . . much less a book than a state of vision, of feeling and of consciousness.”) Throughout, we encounter James at his most expansive and ingratiating, as likely to disarm with a joke about his weight as he is with the arresting phrase “New York state of mind” (casually deployed in 1913, sixty-some years before Billy Joel).

But don’t just take our word for it. Two appreciations, available online, serve as helpful introductions to these books while also making a persuasive case for why they deserve to be rediscovered in the twenty-first century.

The more recent is Adam Gopnik’s review of Autobiographies this month in