After what he called “five years of monstrous misgivings and diabolical labors,” Vladimir Nabokov finished writing Lolita in December 1953 and began submitting it to publishers. “It is overwhelmingly nauseating, even to an enlightened Freudian. To the public, it will be revolting. It will not sell, and will do immeasurable harm to a growing reputation. . . . I recommend that it be buried under a stone for a thousand years.” So went one of the many rejection letters. Five leading publishers—Doubleday; Farrar, Straus; New Directions; Simon & Schuster; and Viking—all turned it down.

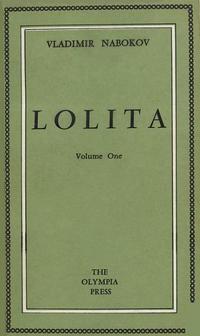

That was when Nabokov’s European agent, Doussia Ergaz, recommended Maurice Girodias of the Olympia Press in Paris, publisher of Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller, and William S. Burroughs. Nabokov was then teaching Russian Studies at Cornell and feared he would be fired unless the book was published under a pseudonym. Girodias would publish it, but only with Nabokov’s name as author. Nabokov agreed but was wary, as he expressed in a letter in July 1955: “You and I know that Lolita is a serious book with a serious purpose. I hope the public will accept it as such. A succès de scandale would distress me.”

Girodias printed 5,000 copies of Lolita in English in September 1955. It sold mostly to English tourists and did not receive any critical attention until, in an interview with the London Times, Graham Greene named it one of the three best novels of 1955. This prompted John Gordon of the Sunday Express to order a copy and to denounce it as “about the filthiest book I’ve ever read” and “sheer unrestrained pornography.” The ensuing brouhaha (Gordon pointed out that Greene had been sued by Shirley Temple “for having said the little girl made her living out of displaying her thighs for the delectation of middle-aged gentlemen”) made Lolita into an international sensation. Responding to Gordon’s attack in Esquire, Dorothy Parker wrote:

I cannot regard it as pornography, either sheer, unrestrained, or any other kind. It is the engrossing, anguished story of a man, a man of taste and culture, who can love only little girls … an anguished book, but sometimes wildly funny, as in the saga of his travels across and around the United States with her…. [Nabokov’s] command of the language is absolute, and his Lolita is a fine book, a distinguished book—alright then—a great book.

The New York Public Library “Sessions” pages, edited by Rodney Phillips and Sarah Funke, recount the dramatic story of the American publication:

Though copies of the Girodias edition were making it into the United States, Nabokov still wished for an American edition. Jason Epstein, then an editor at Doubleday, hoped to convince Doubleday’s president, Douglas Black, to take the novel, by playing upon Black’s desire to refight the court battle he had recently lost over Edmund Wilson’s The Memoirs of Hecate County. In an attempt to gain ground, Epstein arranged for an excerpt (about a third of the novel) to appear in Doubleday’s June 1957 Anchor Review, with critical praise from Partisan Review editor F. W. Dupee. The Anchor volume featured Nabokov’s specially written explanation of the genesis of the novel and his defense of it on the grounds of “aesthetic bliss”: “On a Book Entitled Lolita.”

Throughout the summer and into the fall, Nabokov endured delays and denials by Doubleday, Simon & Schuster and even Putnam’s. He settled on the small independent publisher Ivan Obolensky, but when his offer, too, fell through, Putnam’s made good on an earlier proposal, and went into production.

On publication day [August 18], Putnam’s president, Walter Minton, sent a congratulatory telegram:

EVERYBODY TALKING OF LOLITA ON PUBLICATION DAY YESTERDAYS REVIEWS MAGNIFICENT AND NEW YORK TIMES BLAST THIS MORNING PROVIDED NECESSARY FUEL TO FLAME 300 REORDERS THIS MORNING AND BOOK STORES REPORT EXCELLENT DEMAND CONGRATULATIONS ON PUBLICATION DAY.

By the end of the day, 2,600 orders had been received.

The “blast” referred to by Minton was Orville Prescott’s pan, although Elizabeth Janeway’s review that had appeared the previous day in the Sunday Times was a rave. Lolita would go on to be the first book since Gone With the Wind to sell 100,000 in its first three weeks.

In a 1964 interview for Life Magazine, Jane Howard asked Nabokov, “which of your writings has pleased you most?”

I would say that of all my books Lolita has left me with the most pleasurable afterglow—perhaps because it is the purest of all, the most abstract and carefully contrived. I am probably responsible for the odd fact that people don’t seem to name their daughters Lolita any more. I have heard of young female poodles being given that name since 1956, but of no human beings.