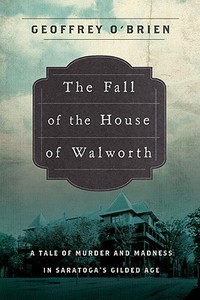

Geoffrey O’Brien, editor-in-chief of The Library of America, recently published his latest book, The Fall of the House of Walworth: A Tale of Madness and Murder in Gilded Age America (Henry Holt). As the book’s title itself makes clear, the literature available to him during his day job influenced his writing, and we asked him to list those works that were particularly on his mind while he wrote this slice of American history.

In my book The Fall of the House of Walworth, I sought to reconstruct the inner and outer worlds of a distinguished but remarkably ill-fated nineteenth-century family whose lives were caught up in various kinds of mania and one spectacular murder. Although the book is non-fiction, the literary antecedents I bore in mind as I worked tended to be fictional. These were six that helped particularly in setting my course:

Edgar Allan Poe: “The Fall of the House of the Usher.” Poe was favorite reading matter for several of the Walworths, and the neurasthenic Roderick Usher might have served them as a perverse role model. My book’s title pays unavoidable homage to Poe’s long lingering influence.

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The House of the Seven Gables. The ancestral curse of the Pyncheons, symbolized by their elaborate dwelling-place, rhymed nicely with the 55-room Walworth Mansion and its gloomy heritage.

Charles Brockden Brown: Wieland. The ancestor of American Gothic, Brown sounded themes of trance, madness, and religiously inspired murder in this dreamlike concoction.

Herman Melville: Pierre, or The Ambiguities. The early chapters of this often grotesque successor to Moby-Dick powerfully evoke the world of upstate New York that Melville knew well.

James Fenimore Cooper: The Pioneers. Cooper’s fictionalized version of Cooperstown, founded by his father, informed my sense of the earlier period in which Chancellor Reuben Hyde Walworth established his family’s power and prosperity.

Dashiell Hammett: The Dain Curse. A more modern version of Gothic from the 1920s, Hammett’s thriller, tinged with opium and cultishness, was a model of storytelling.

The New York Times has posted a copy of its June 4, 1873 article about the murder at the center of O’Brien’s book.

Laura Miller notes in Salon that “O’Brien was fortunate: The Walworths were prodigious writers—of letters, journals, poetry, monographs and, yes, novels.” But, Thomas Mallon adds in his New York Times review, “however central the novelist Mansfield Tracy Walworth (1830–73) may be to O’Brien’s crackerjack new history of one family’s mayhem, it seems safe to say that he will not soon be joining Welty, Wharton and Whitman at the right-hand reaches of The Library of America’s long, august shelf.” Or, as Geoffrey himself writes in the book, Walworth’s fiction displayed a “staggering slovenliness.” In at least one of the novels, “once Mansfield became embroiled in cataloging women’s clothing, it was difficult for him to get back to the story.”