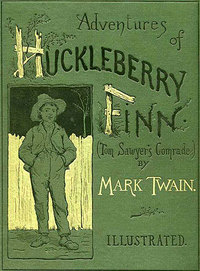

Since 1982, bookstores and libraries across the country have celebrated Banned Books Week (September 25 to October 2), commemorating the First Amendment and the freedom to read. The campaign also focuses attention on the harm caused by actual or attempted efforts to censor, suppress, and ban works of literature from schools and libraries. And 125 years ago, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn helped start all the ruckus.

When Mark Twain heard that the Concord Public Library in Massachusetts had banned Huckleberry Finn just weeks after it was published, he shrewdly saw it as a great advertising opportunity. On March 18, 1885, the New York Herald reported, perhaps a bit cheekily, that the library committee offered reasons “weighty and to the point”:

One of the Library Committee, while not prepared to hazard the opinion that the book is “absolutely immoral in its tone,” does not hesitate to declare that to him “it seems to contain but very little humor.” Another committeeman perused the volume with great care and discovered that it was “couched in the language of a rough, ignorant dialect” and that “all through its pages there is a systematic use of bad grammar and an employment of inelegant expressions.” The third member voted the book “flippant” and “trash of the veriest sort.” They all united in the verdict that “it deals with a series of experiences that are certainly not elevating,” and voted that it could not be tolerated in the public library.

On April 4, the Hartford Courant published Mark Twain’s reaction, which he wrote in the form of a letter responding to the Concord Free Trade Club’s invitation to become an honorary member:

. . . a committee of the public library of your town have condemned and excommunicated my last book and doubled its sale. This generous action of theirs must necessarily benefit me in one or two additional ways. For instance, it will deter other libraries from buying the book; and you are doubtless aware that one book in a public library prevents the sale of a sure ten and a possible hundred of its mates. And, secondly, it will cause the purchasers of the book to read it, out of curiosity, instead of merely intending to do so, after the usual way of the world and library committees; and then they will discover, to my great advantage and their own indignant disappointment, that there is nothing objectionable in the book after all.

Banned Book Week continues the spirit of Twain’s response. Although Huckleberry Finn didn’t make the top ten this year (it did in 2007), the Jacket Copy blog recently listed the most-challenged books based on the 460 challenges reported in 2009 to the American Library Association. The ALA has created a kind of honor roll: a page itemizing some of the most “frequently challenged classics,” with the reasons and the outcomes. The honorees range from Go Tell It On the Mountain by James Baldwin to As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner to Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth. A state-by-state listing of events celebrating Banned Books Weeks is available on the ACLU’s site.

Pick a banned book to read this week.