Mark Twain was among the painters and writers asked in 1883 to contribute sketches and letters to be auctioned at the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund Art Loan Exhibition in New York to raise money to build the pedestal that would hold the Statue of Liberty. Twain sent a check and an alternative proposal, “Why a Statue of Liberty When We Have Adam!”

What do we care for a statue of liberty when we’ve got the thing itself in its wildest sublimity? What you want of a monument is to keep you in mind of something you haven’t got—something you’ve lost. Very well; we haven’t lost liberty; we’ve lost Adam.

Another thing: What has liberty done for us? Nothing in particular that I know of. What have we done for her? Everything. We’ve given her a home, and a good home, too. . .

But suppose your statue represented her old, bent, clothed in rags, downcast, shame-faced, with the insults and humiliation of 6,000 years, imploring a crust and an hour’s rest for God’s sake at our back door?—come, now you’re shouting! That’s the aspect of her which we need to be reminded of, lest we forget it.

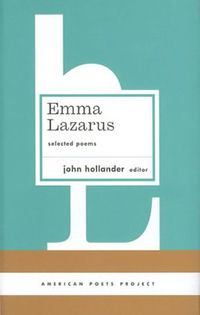

Twain’s statue of the biblical Adam didn’t get built. Writer Constance Cary Harrison also had to conjure an image of Lady Liberty to persuade Emma Lazarus to contribute. When first approached, Lazarus demurred. She didn’t write “to order” and made fun of her “portfolio fiend” friend. But Harrison had read Lazarus’s articles about the plight of Russian Jews abroad and knew of her volunteer work at the hospital on Ward’s Island:

“Think of that Goddess standing on her pedestal down yonder in the bay, and holding her torch out to those Russian refugees of yours you are so fond of visiting at Ward’s Island.” The shaft sped home—her dark eyes deepened—her cheek flushed—the time for merriment had passed—she said not a word more, then.

“The New Colossus” was the only poem read at the exhibition. It was printed in the catalogue, in Art Amateur magazine, and widely reported in the press. Another contributor, James Russell Lowell, wrote to Lazarus from London in December 1883:

I must write again to say how much I like your sonnet about the statue—much better than I like the Statue itself. But your sonnet gives its subject a raison d’être which it wanted before much as it wanted a pedestal. You have set it on a noble one, saying admirably just the right word to be said, an achievement more arduous than that of the sculptor.

Lowell grasped Lazarus’s great achievement. As Paul Auster has written, “The New Colossus” reinvented the statue’s purpose, turning Liberty into a welcoming mother, a symbol of hope to the outcasts and downtrodden of the world.” “Mother of Exiles” replaced “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

But the poem faded from memory even before the statue was erected. At the dedication on October 28, 1886 (124 years ago today), “The New Colossus” was not read. Lazarus died a year later of Hodgkin’s Disease, her poem forgotten. In 1903 Lazarus’s friend Georgina Schuyler raised enough money to engrave the poem on a bronze tablet and place it on the second floor of the Statue of Liberty. There it languished in obscurity until the fiftieth anniversary of the statue spurred the Slovenian-American journalist Louis Adamic to begin a crusade to popularize it.

It caught on. Immigrant screenwriter Billy Wilder had Victor Francen recite it at a Fourth of July celebration in the 1941 film Hold Back the Dawn. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), Priscilla Lane delivers its four most famous lines (“Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free. . .”) to an enemy agent at the top of the Statue of Liberty. In 1945 the bronze tablet was moved from the second floor to the main entrance.