John A. Williams in 1962 (Carl van Vechten / Library of Congress) and illustration from early edition of Moby-Dick by Augustus Burnham Shute (Public Domain)

Hailed by Chester Himes as “a blockbuster, a hydrogen bomb” when it was published in 1967, John A. Williams’s The Man Who Cried I Am is at once a panoramic novel about systemic racism and a deeply personal transmission from the heart of the Parisian Black literary expat scene. Centering on Max Reddick, novelist, journalist, presidential speechwriter, and authorial alter ego, the book weaves the global history of Black American experience in the decades after World War II—complete with characters based on Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X—with a propulsive, high-stakes plot that freely mixes elements of thriller, satire, and roman à clef.

Merve Emre (merveemre.com)

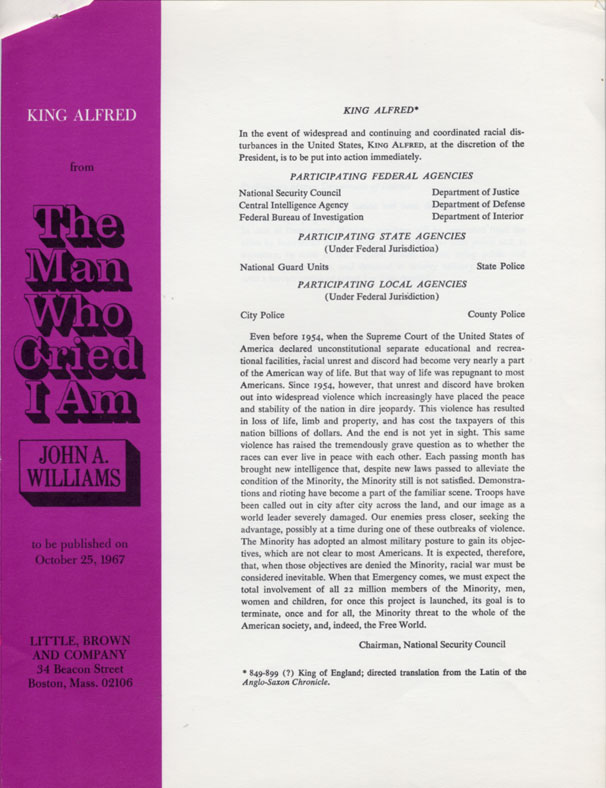

At the heart of the book lies the King Alfred plan, a top-secret government document outlining preparations “to terminate, once and for all, the Minority threat to the whole of the American society” in the event of widespread racial unrest. Part fiction-within-fiction, part viral conspiracy theory, part gonzo marketing stunt, this dangerous memo is but one point of contact between reality and invention in a novel replete with such transgressions—guerilla raids—against the prevailing myths of white supremacy in the era of the civil rights movement and the Cold War.

In a conversation with LOA, Merve Emre, who wrote the introduction to our recently published paperback edition of Williams’s masterpiece, discussed the novel’s astonishing scope, its nuanced examinations of race and gender, and why she’d teach it alongside Moby-Dick.

LOA: Who was John A. Williams? What biographical experiences informed the creation of The Man Who Cried I Am?

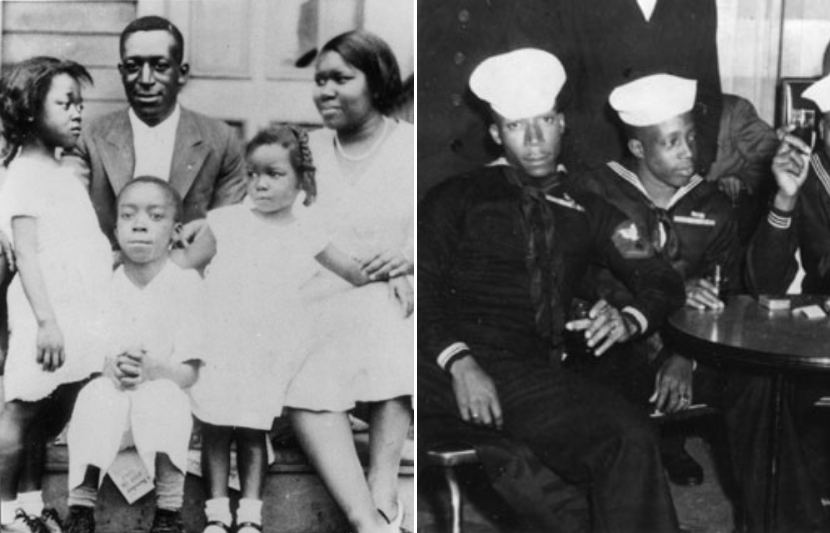

Merve Emre: John A. Williams was born in 1925 and grew up in Syracuse, New York. He had a fairly happy childhood until, at seventeen, he enlisted in the still-segregated Navy and was deployed to the South Pacific. It was there, during World War II, that he first confronted the possibility of his own death. It was not presented to him by the fighting, but rather by his encounters with white naval officers, who at one point pulled him aside and, as a joke, they said, put a gun to his head and threatened to pull the trigger.

Photograph of the Williams family in Syracuse, New York, circa 1934; John A. Williams in Oakland, California, 1946 (University of Rochester: Rare Books and Special Collections)

When Williams returned to the United States after the war, he enrolled in college on the GI Bill. After he graduated in the early 1950s, he moved to New York and started to write novels while working as an ad man and publicist. His first few novels were minor successes, often marketed by his white publishers as books fixated on the anger of Black men in America.

First-edition cover of The Man Who Cried I Am (Little, Brown, 1967)

This was a form of tokenization that Williams deeply resented: the fact that if you were a Black man writing in the United States, you had to stand not just for all Black people, but also for the most violent feelings that they were believed to harbor. He wanted badly to find a way out of this bind, whereby the Black writer had to not only be representative of his race, and only his race, but also the representative of his race’s history of oppression and nothing more.

When he wrote The Man Who Cried I Am, Williams put all of that fury that he was, in a sense, trying to deny or to avoid into the narrative style of the novel—which is why, I think, we have a work that burns so hot for so long. It is a tremendously intense, tremendously outraged novel, one whose anger is at times very much about race and racial oppression, but at other times about the great difficulty of being a human in history, which one moves through in various states of muddle and mystification.

LOA: The novel is filled with discussions of race, white supremacy, the differences between Black people and white people. But at the same time, in the psychology of the book, those notions are constantly being punctured and complexified. Could you speak to the subject of race in The Man Who Cried I Am and how that compares to other writers of Williams’s era who tackled the topic of anti-Black racism in their work? How does Williams do it differently?

ME: It is impossible to read The Man without thinking of two texts by authors who appear in the novel: first, Richard Wright’s Native Son, and second, James Baldwin’s response to Native Son, “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” Williams is entering the obviously Oedipal argument between these two writers, in which Wright wrote a novel that testified to some of the historical and social determinants of a Black man’s character, which Baldwin had critiqued for how it did a disservice to the individuality of Black people by allegedly reducing them to the social and political conditions established by white supremacy.

Richard Wright in Paris in October 1957 (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Williams is wading into that two-decade-long controversy, as if to say, “Here’s how you write a novel that recognizes the centrality of race, class, and gender to the psychology of an individual character while demonstrating that that same psychology will resist any attempt to reduce it to these factors alone.” The Man Who Cried I Am is extraordinarily anxious about masculinity, about Blackness, and about Americanness. It’s mobilizing all of those identitarian categories and showing how they have shifted from 1945 to the novel’s present of the mid-1960s. But at the same time, it is insisting that any individual whom we seek to typify by means of those categories will always have a particular story. Whatever man we choose to center in that story will have his own way of crying, “I am.”

The key to the novel is how it tries to thread the needle between Wright and Baldwin. It insists that, to do so, the novel will need to be very big, very expansive. It will need to switch, as this one does, from social realism to reportage to detective story to paranoid thriller to roman á clef. It will have to do all of this heavy lifting with genre to make sure its protagonist can never feel entirely known or typed, because what it means to be a Black American man in a 1940s roman á clef will be different from what it means to be a Black American man in a 1960s paranoid thriller.

LOA: In addition to the vast geographic and temporal scope, there are also many remarkable passages that get us out of the plot and into Max Reddick’s mind as he contemplates the historiography of racism and his own place in it. There’s the constant refrain of being the man to meet the historical moment, but there’s the sense that the only way to do that is to look far back into the past.

ME: Max Reddick is by profession a journalist, but his consciousness is much more that of the philosopher of history. He is always trying to understand the relationship between the individual—and, in particular, an individual with reformist or revolutionary aspirations who believes he has a strong understanding of the historical conditions in which he’s operating—and the institutions that would seek to assimilate the individual to the status quo.

To make that historical consciousness evident, Williams has to depict the extraordinary eventfulness of the ’40s, the ’50s, and the ’60s, across North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa, but he also has to depict the analysis of that eventfulness. One way the novel uses its massive frame to its great advantage is by letting us inhabit Max’s thoughts for long stretches of time; there are even sentences when it shifts from close third-person omniscient narration to an almost first-person direct address. The narrative style is saturated by Max’s vocabulary, by his judgments. When you come to know that voice well, when you become sufficiently familiar with its rhythms, you see how the narrative is trying to move us through Max’s time while also allowing him, implicitly, to interpret the time he’s moving through for us, to synthesize the different, but related, developments that are taking place across the world.

WATCH: John A. Williams and Samuel F. Yette discuss the topic of genocide on the Black Journal television show in 1971

LOA: Despite the novel’s scale, it’s still rooted in individual relationships. There’s the role of male rivalry, artistic and sexual, that runs through the book. Meanwhile the romances between men and women expose a different relation to power, political access, and sexual freedom. How do these friendships, acquaintanceships, affairs, and marriages comment on or contradict the politics of The Man Who Cried I Am?

ME: Williams’s characters, like most of us, want to imagine that their personal relationships or private lives stand apart from the social and the political in a way that is protective and restorative. We like to think that our best, or most important, relationships give us a sense of who we are, or we can be, outside the sight of the world. In the novel, the moments when the characters are negotiating the intimacy of their relationships are literally set in isolated locations. When Max and his mentor-slash-rival Harry Ames go hunting, for example, they are alone in the woods, not in Harry’s house, where they can be spied on by his wife or house guests, or in the cafés of Paris, where they can be spied on by the U.S. government. They appear to exist, for a moment, in a world apart.

Similarly, when Max and Margrit, his white Dutch wife, go on their honeymoon, they’re on a relatively unpopulated island in the Pacific. Yet then there’s a reference to B-52s flying overhead, as if to remind them—and us—that there is no world apart from the social and the political. Even to conceive of your marriage or your friendship as a place apart is already to put it into relation to society, because that’s how the relationship’s autonomy derives its value—from being a place where you can pretend that the problematics of race or gender or sexuality or nationality don’t matter. There’s always a crushing disappointment in realizing how unsustainable that fantasy is. If, in this novel, one of the primary tensions is between the individual and the institutions to which he belongs, then the secondary tension is between who the individual is in the view of the public and who the individual can be in his or her intimate relationships.

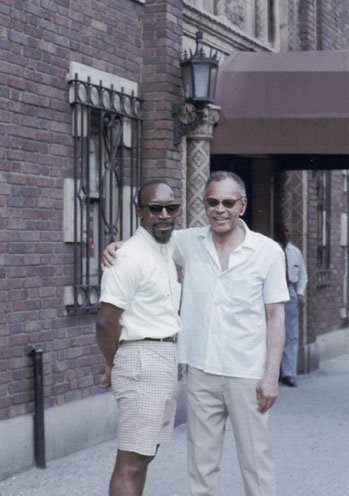

John A. Williams and Chester Himes in New York, 1968 ( Lori Williams / University of Rochester: Rare Books and Special Collections)

That tension is particularly fraught in the novel’s romances, because these are where Max hopes the most ardently to get away from Blackness as something that determines him. It’s also where the disappointment of realizing he can’t get away from it is the most acute. The first of Max’s two main romances in the novel is with a young Black woman named Lillian whose parents are members of the upwardly mobile Black bourgeoisie. They don’t understand why she wants to marry a writer; they don’t think he’ll be able to provide for her, and Max feels a great deal of anxiety about that. Max feels tremendous anger at himself for not compromising—for not wanting to give Lillian the life of bourgeois uplift—and at Lillian, for being so committed to her parents’ vision and expectations that she ends up securing the conditions of her own death.

The second romance is Max’s marriage to Margrit. She begins the novel; she ends the novel; she is the person Max goes to when he knows he is dying and needs to impart vital information Harry has left him to someone. She’s the person he trusts. When they get married, he believes their love will be able to overcome the fact that he’s Black and she’s white. But in the three years of their marriage before they end up estranged from each other, his history, his anger, gets in the way of the mutual understanding he seeks with her from the beginning. Max is keenly aware of what his marriage to a white woman represents. And he marries her at precisely the moment that Minister Q, a character based on Malcolm X, is rising to public attention by preaching not integration and peaceable coexistence, but instead for African Americans to return to Africa and to promote the creation of a pan-African union.

One of the interesting things about the novel is its thinking about how one’s racial politics can scale. What are the politics of marrying into a bourgeois family and how are they or how are they not analogous to reformist or integrationist politics? What are the politics of an interracial marriage and how are they or how are they not analogous to the politics of countries marrying one another in a global or an international alliance? A marriage and a global political consortium are two entirely different beasts, and to not recognize that—or to recognize it but not be able to live the truth of that difference—is part of what Max struggles with throughout the novel.

EXPLORE: FBI documents studying Richard Wright, compiled by William J. Maxwell for F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature (2015)

LOA: It’s fascinating what you say about the relationships and marriages being analogous to the geopolitical movements of the novel, and one of the ways this is most explicitly expressed is in Max’s fascination with post-World War II Europe and the Holocaust. Even the King Alfred plan echoes the mechanisms of the Holocaust and the official language of genocide.

ME: It’s an interesting question for our moment as well, which is how do you compare—and for what ends and what purposes—different programs of the systemic extermination of a people? That’s another reason for the book’s large frame, because Williams wants to draw these transcontinental, transhistorical comparisons without being glib about it. It would be so easy to say that the Holocaust is exactly like the King Alfred plan. One thinks of Sinclair Lewis’s famous title It Can’t Happen Here and there’s a temptation to treat the novel, especially its end, as an it-can’t-happen-here narrative.

But for that not to be lazy or glib, Williams needs to build from the bottom up a vision of systemic racism in the United States, so that by the time you get to the King Alfred plan, it seems like the natural outcome of American history. And while it’s in certain ways comparable to the Holocaust, it is in no way equivalent to the Holocaust. It matters, for instance, that there is no Hitler figure or SS. There are only the various shadowy officers and administrators of the American government.

Williams is taking a page out of the playbook of systemic racism, which is that the way to really assert your power over people is to get in their heads and never let them prove one way or another what the full extent of your power means.

One of the interesting frustrations that is repeated in the novel is that Max believes he has found a smoking gun as a reporter, but then the person whom he needs to confirm that evidence—or the evidence itself—is not available. Every discovery in the novel is always stopping short of absolute proof, definitive evidence that a crime has been committed or an injustice has occurred. There is a whole realm of inaccessibility in the novel, of inaccessible characters, of inaccessible documents, of inaccessible places, where, we are led to believe, people are making the decisions that result in racist policy, in discrimination, in violence, and in death.

But it seems important to this novel that there is not a single person one could point to as a villain, and even the people we might want to point to as villains are often complicated figures. They are Black Americans who have been asked to spy on other Black Americans, and so they’re traitors, but they’re also brothers. They are white publishers who are vulgarly tokenizing but are also allowing Black authors’ work to be read and circulated. It’s not a moralizing novel in that sense, and its anger is in part generated by the fact that neither it nor its main character can be moralizing in the ways that we often want to be. We cannot point to good people and evil ones because everyone is in some ways a complex vector of impersonal historical or institutional forces that are bigger than an individual.

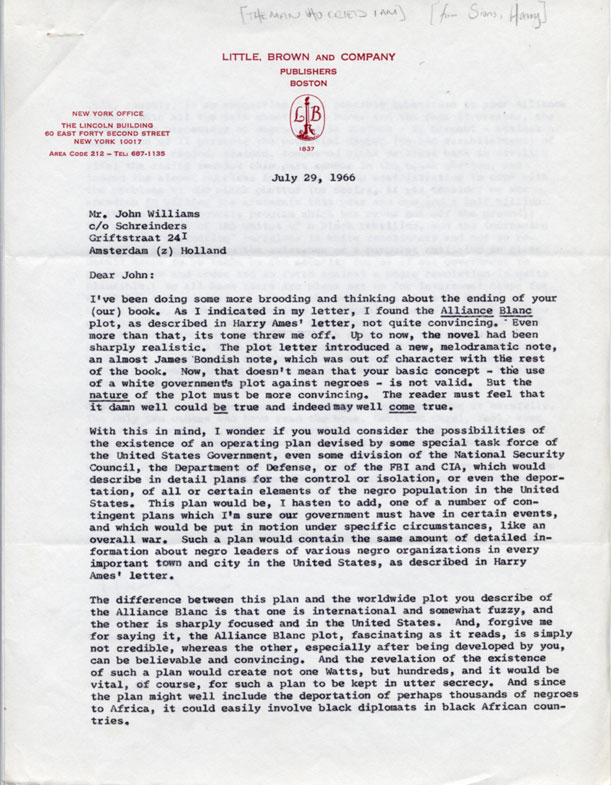

Letter from Harry Sions to John A. Williams discussing revisions to the novel’s ending (University of Rochester: Rare Books and Special Collections)

LOA: King Alfred seems to exemplify that idea, being at once a bloodless, bureaucratic document and a startling, borderline absurd piece of fiction-within-fiction. For example, there’s the line hand-waving away the plan’s proposed method of extermination, alluding to secret “vaporization techniques” that may as well be lifted from science fiction. And then there’s the hand-drawn map of America that looks like it was made by a child.

ME: The King Alfred plan, in the initial drafts of the novel, was judged by Williams’s editor, Harry Sions, to be not believable, and the maps and the faux-bureaucratic documents were generated in response to that claim. It’s interesting that putting together a couple of fake memos and a crudely drawn map would give this a kind of facticity that would fit the overall tone of the novel, with its very thinly veiled references to real people and its overt references to real events. It was part of trying to make the novel’s claim to life stronger. But still, it’s impossible to believe that the plan is real because it appears so hastily patched together, and indeed so cartoonishly nefarious that it almost seems like a child came up with it.

At the same time, we have to realize that “vaporization” was something that had happened only thirty years before in Germany. The violence of history can actually be so shocking that even believability tilts into unbelievability, and comedy might be our only way of dealing with it. We laugh because the horrors are too great for us to confront in any other way.

King Alfred had an interesting life after the novel, as well. Williams, from his experience as an ad man and a marketer, knew how effective the plan could be for selling the novel. Prior to the book’s release, he made copies of it and put them in envelopes and left them on the subway in New York, and those copies began to circulate as far as San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, even internationally. It really made the plan a kind of conspiracy theory in the popular imagination; the afterlife of the King Alfred plan has been as a document that has been read entirely straight, without a sense of its comedy or its irony. And that makes the novel an interestingly dangerous object. Or rather, it takes the anger of the novel and de-mediates it, to put it toward a dangerous purpose.

Excerpt from the King Alfred plan (Little Brown, 1967)

In some ways, Williams is taking a page out of the playbook of systemic racism, which is that the way to really assert your power over people is to get in their heads and never let them prove one way or another what the full extent of your power means. In transmitting the King Alfred plan through word of mouth, Max is mirroring what he has learned about power and its circulation, which is that you don’t want it to be traced to a source. You want it to be diffuse. You want it to be everywhere and nowhere.

LOA: Separate from the complex discussions of race in this novel, there’s also a lot about gender, not just in the relationships between men and women, but also in what the novel suggests it means to be a man or a woman. How does Max think of the women in his life, and how do they influence him? What is the novel’s perspective on gender and the power differential between men and women?

ME: When we first meet Max, he’s sitting in a café in Amsterdam staring at the women going by and sort of looking up their skirts: “Once in a while, Max would see a girl pedaling saucily, not caring if her knees blocked out the sights above or not. Max would think: Go, baby!” Of course, there’s something voyeuristic about this behavior. But on the other hand, that “go, baby!” is more like “you go, girl!” It’s not an expression of desire so much as a statement of appreciation of the freedom that these women enjoy.

That seems to be one of the questions about gender that is raised immediately in the book, where we have Max, a Black American man, asking who has more freedom in this world? Is it a Black man, a white woman, a white European woman, or the African women Max has encountered in Lagos? Instead of thinking of it necessarily as an expression of desire, that appreciative utterance for the Dutch women’s freedom frames them more as allies, although I would not want to push that point too far.

WATCH: Black Writers in Paris, the FBI, and a Lost 1960s Classic: Rediscovering The Man Who Cried I Am

But this is also a novel in which so much of a person’s sense of life, particularly the sense of life that is preserved when the whole world seems to be conspiring against it, comes from sexual vitality. The question for Max is, now that he cannot be a sexual being anymore on account of his illness, now that he is limping toward death and bleeding out of his anus, which he explicitly compares to menstruation, who is he and who can he be? I think that gaze we observe in the café, while maybe maintaining some misogynistic desire, has really moderated into something that is much less covetous, much less appropriative, and much more sympathetic.

LOA: If you were teaching this novel or introducing it to curious readers, what would you tell them to pay attention to?

ME: I would teach it as part of the tradition of what some have called “the Great American Novel”—these big, multi-genre novels that are trying to understand what America is by putting America or representatives or embodiments of America out into the world. And the Great American Novel I would pair The Man with would be Moby-Dick. I would want to give students a sense of the nineteenth-century version of what happens when you take these highly particularized American concepts of race and send them sailing around the globe, and what then happens when you do that a hundred years later in the postwar period.

The novels have similar intensely homosocial dynamics, similar romances of race and of interracial contact or communion. They are also both novels about the circulation of information, about obsessive quests. Ahab has his white whale, while Max’s quest is to find the power of whiteness, or where it is that white power comes from.

Merve Emre is the Shapiro-Silverberg Professor of Creative Writing and Criticism at Wesleyan University and a contributing writer at The New Yorker.