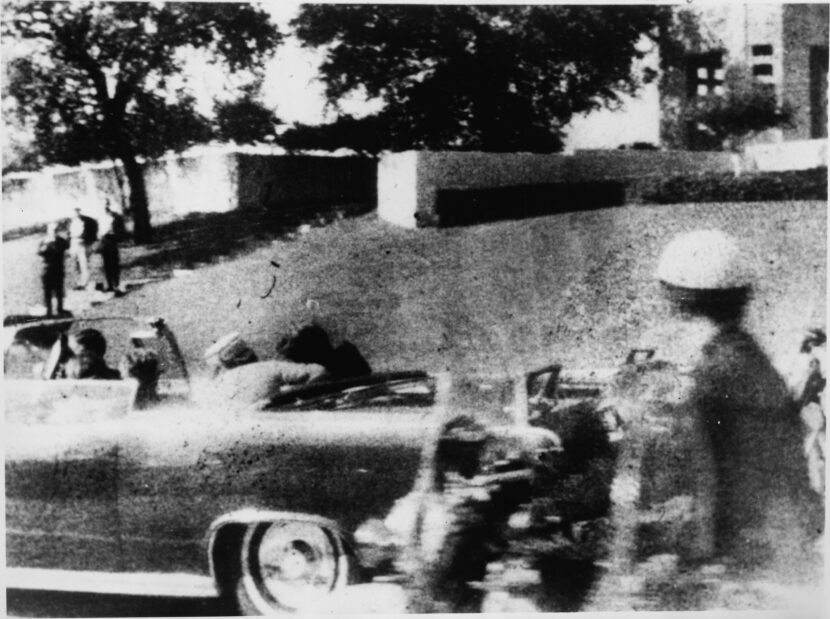

Polaroid photograph of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, taken immediately after the fatal shot (Mary Ann Moorman / Public Domain)

The assassination of John F. Kennedy, which took place sixty years ago on November 22, remains a tragic and indelible blot on our nation’s history. It’s also, judging from the nigh-uncountable books that take the event—or some version of it—as their subject, an irrepressible part of the American imagination. In the six decades since shots rang out in Dealey Plaza, JFK’s death has fueled an immense range of artistic responses, many of them by writers in the LOA series.

Among the best-known examples is Don DeLillo’s Libra (1988), which tells a probable (though not strictly factual) life story of Lee Harvey Oswald. Despite diverging substantially from the historical record, the book speaks truth to the fuzziness of a history cloaked in conspiracy, finger-pointing, and political opportunism.

In his 2022 preface to the novel (written especially for the LOA edition), DeLillo writes about the almost holy power held by the assassination’s endlessly remixed details:

Where were you when Kennedy was shot? This is what people said incessantly after the events of November 22, 1963. And for the next two decades, the opinions and theories and controversies continued. How many shots—three or four or more? How many shooters—one or two or more? And the terms became a religious litany: the Motorcade Route, the School Book Depository, Dealey Plaza, the Grassy Knoll, the Colonnade, the Stockade Fence, the Triple Underpass, Stemmons Freeway, Parkland Hospital.

Bystanders taking cover after shots were fired in Dealey Plaza (Cecil W. Stoughton / Public Domain)

An avid researcher, DeLillo notes the contents of his shelves filled with books “all generated by the same moment in Dallas.” Of special interest is the testimony of Marguerite Oswald, Lee’s mother, “speaking in her hip-hop surreal fashion, a literary marvel of its own right.”

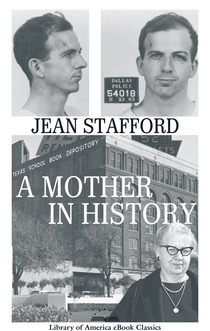

That marvel is A Mother in History (1966), Jean Stafford’s interview with the sole surviving parent of the accused assassin. Alternating between delusion, grief, anger, and hope that time will clear her son’s name, Marguerite Oswald is at once an unreliable narrator and zealous mythologizer, speaking for posterity while barely holding on to reality.

Dishing to Stafford in a living room stuffed with bric-a-brac and swimming in the writer’s cigarette smoke, she memorably declares:

Now maybe Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin. But does that make him a louse? No, no! Killing does not necessarily mean badness. You find killing in some very fine homes for one reason or another. And as we all know, President Kennedy was a dying man. So I say it is possible that my son was chosen to shoot him in a mercy killing for the security of the country. And if this is true, it was a fine thing to do and my son is a hero.

Stafford, “staggered by this cluster of fictions stated as irrefutable fact,” manages to respond, “I had not heard that President Kennedy was dying.”

Transfer of John F. Kennedy’s casket to Air Force One (Cecil Stoughton / John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

Where, amid all this freewheeling conjecture and desperate longing masquerading as belief, are the facts about November 22 to be found? Stafford, hoping to reground herself in truth following her dizzying encounter with Oswald, visits the scene of the shooting:

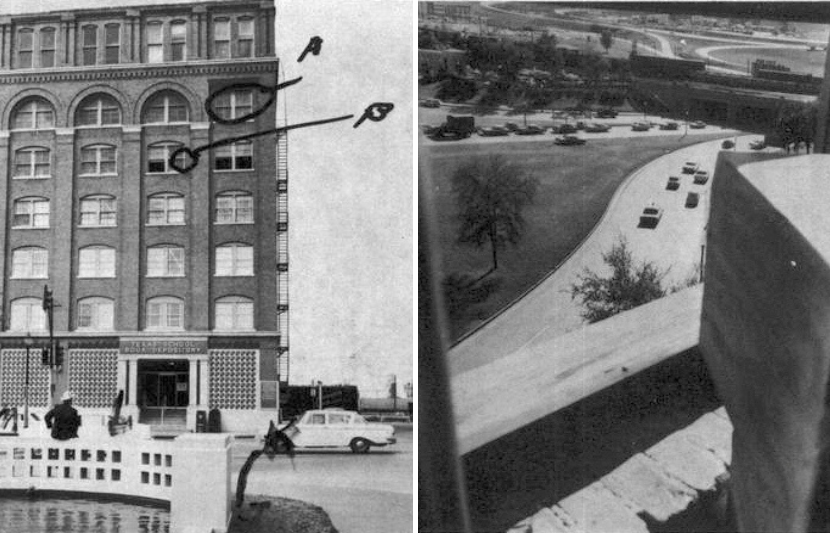

As we entered Dallas and drove along the route of the President’s caravan, I observed, as I had the other two times I had been over this same ground, that the distance between the sixth-floor window of the Texas Book Depository and the place where the car, slowing for a turn, had been, seemed to be much less than it had appeared in photographs. I was struck, moreover, by the fact that between the window and the target there was no obstruction of any kind to challenge aim or deflect the attention, no eave or overhang or tree. The drop shot, from a steadied rifle, was fired on a day of surpassing clarity; the marksmanship of the gunner did not have to be remarkable.

The Texas School Book Depository and view from the sniper’s nest (Public Domain)

Pierced by the apparent plausibility of the official version, the haze of conspiracy seems to lift, if only momentarily. To get at the unvarnished truth, we must go back to before the rumors started swirling, when recollections of the day were fresh and had not yet proliferated, to use Stafford’s memorable phrase, “like mushrooms in a pinewoods after a soaking rain.”

For a portrait of the assassination’s aftermath rooted in eyewitness accounts and acute reportorial skill, look to Jimmy Breslin’s columns included in the forthcoming LOA edition of his essential writings, which take us from the emergency room of Parkland Hospital as doctors labor in vain to save the president’s life to Arlington National Cemetery, where Kennedy was buried on November 25.

But even in these vivid depictions, shed of intrigue and insinuation, we see how hard the historical actors struggle to make sense of what they’re seeing, how they fit into the frame of American history as it unfolds. The priest who delivers Kennedy’s last rites sums up the feeling when individuals suddenly find themselves swept up in the current of momentous events:

I’ve been a priest for thirty-two years. The first time I was present at a death? A long time ago. . . . But this. This is different. Oh, it wasn’t the blood. It was the enormity of it. I’m just starting to realize it now.

The sense of being overcome by the significance of Kennedy’s death, the miniaturization of the individual in the face of such world-historical developments, runs through the testimonies Breslin captures.

And yet, it is the profile of Clifton Pollard, the man who dug JFK’s grave at Arlington, that gives us perhaps the most humane and humble picture of a person touched by the assassination. Somehow it is this figure, a forty-two-year-old laborer, who manages to put the tragedy in its proper perspective, beyond questions of who pulled the trigger and why and who was really behind it all. Life goes on, grass grows over graves, and history subsumes us all in the end. Memory and myth merge into Byzantine meta-narratives presented as puzzles for future generations to solve.

Breslin writes:

Clifton Pollard wasn’t at [Kennedy’s] funeral. He was over behind the hill, digging graves for $3.01 an hour in another section of the cemetery. He didn’t know who the graves were for. He was just digging them and then covering them with boards.

“They’ll be used,” he said. “We just don’t know when.”

“I tried to go over to see the grave,” he said. “But it was so crowded a soldier told me I couldn’t go through. So I just stayed here and worked, sir. But I’ll get over there later a little bit. Just sort of look around and see how it is, you know. Like I told you, it’s an honor.”

Jacqueline Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy walk away from John F. Kennedy’s casket at Arlington National Cemetery (Public Domain)

Interested in getting more articles on literature and history before they’re published on our website? Sign up for our e-newsletter and e-mail promotions (we’ll never spam you or share your e-mail with any other company).