Hippies in an apartment, 1969 (Marion S. Trikosko / Library of Congress)

Amid the social and political ferment of the 1960s, an ambitious generation of American crime writers tunneled into the nation’s collective paranoias to unearth bracing tales of murder, thievery, and all-around malfeasance that spoke to the dark heart of a transformative decade. Flipping noir tropes on their head in novels that forthrightly address the era’s anxieties—structural racism, drug abuse, sexual freedom—genre titans such as Chester Himes, Patricia Highsmith, Richard Stark, and Margaret Millar tweaked the whodunnit formula with newer, thornier questions: Why do it? To whom? And what really happened, anyway?

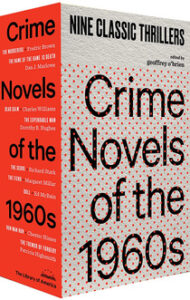

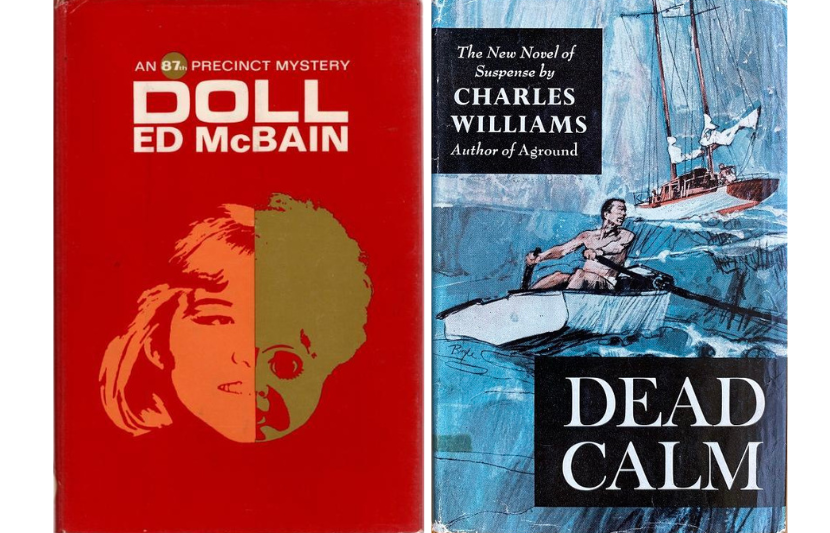

In the recently published two-volume Crime Novels of the 1960s, edited by Geoffrey O’Brien, readers encounter a midnight world of dangerous minds, wily safecrackers, straight and crooked cops, and neurotic mystery writers themselves. From Ed McBain’s breakneck police procedural Doll to Dorothy B. Hughes’s late-career bullseye The Expendable Man, the nine books gathered here complicate and expand our understanding of the tectonic shifts that rocked U.S. society in those years—and continue to shape our culture today.

Over e-mail, O’Brien spoke to LOA about crime writing’s intersection with high literature, why Highsmith’s The Tremor of Forgery reminds him of Camus, and which work in the collection he’s reread more than any other.

LOA: In your introduction to the volume, you write that 1960s American crime fiction channels many of the era’s political and cultural preoccupations: “urban chaos, racist hatreds, proliferating drug use, the suspicions and jangled nerves of suburban enclaves, the nihilistic rejection of established moral codes, the dissolution of personality itself.” How does this stand in contrast to the noir of the 1940s and ’50s? What changes in the nation’s self-conception across these decades?

Geoffrey O’Brien: None of those ills and issues were new in the ’60s, but they had become harder to ignore. Rampant heroin use, police racism, and pedophilia, for instance, figure prominently in several of these books, and not as lurid aberrations.

First-edition covers of The Expendable Man by Dorothy B. Hughes (Random House, 1963) and Run Man Run by Chester Himes (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966)

In Run Man Run, Chester Himes writes: “White cops were always shooting some Negro in Harlem. This was a violent city, these were violent people.” In Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man, the imperiled narrator reassures himself that Arizona “wasn’t the Deep South,” but encounters some contrary realities.

Fredric Brown (Centipede Press)

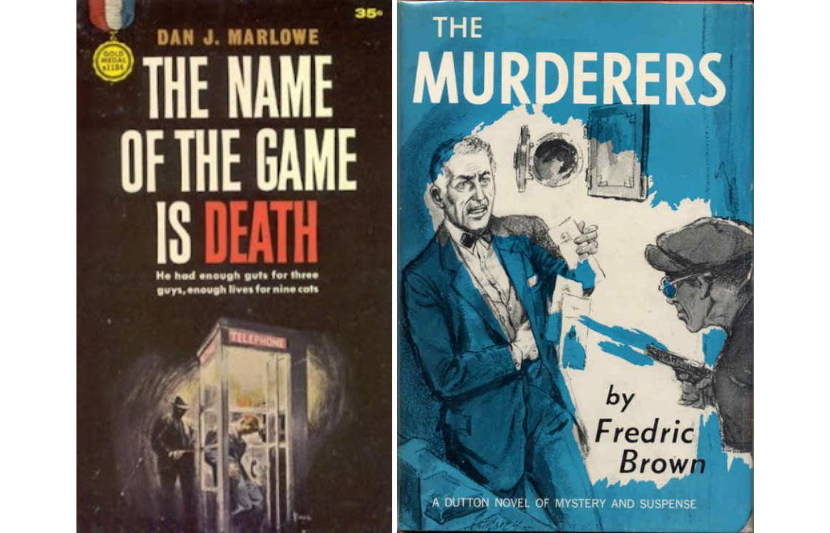

At the same time, outsider viewpoints are more in evidence than in earlier decades’ crime fiction. In Fredric Brown’s The Murderers, we see everything through the eyes of a cynical, eventually murderous narcissist, but none of the Hollywood hangers-on around him seem much better. Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death and Richard Stark’s The Score channel the viewpoints of professional criminals with their own, thoroughly antisocial codes of behavior.

Margaret Millar (womencrime.loa.org)

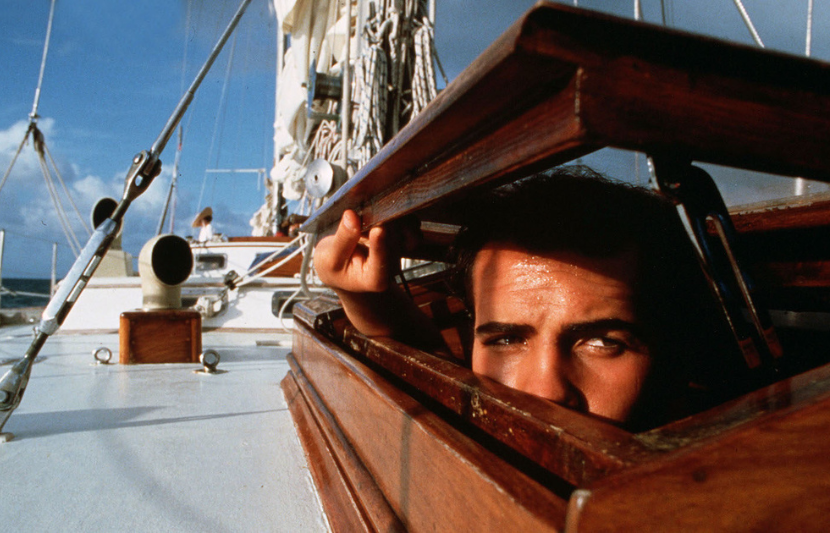

The couple at the center of Charles Williams’s Dead Calm is heroic in an old-fashioned sense, but they prefer a seagoing existence outside society altogether. By contrast, the outwardly serene suburban life in Margaret Millar’s The Fiend emerges as oppressively claustrophobic and rife with paranoid suspicions.

LOA: Formal experimentation comes to the fore in several of these books, such as the clinical abstraction of Stark’s The Score and the recursive, metafictional approach of Highsmith’s The Tremor of Forgery. What do these boundary-pushing works tell us about the development of the crime genre in the 1960s and its relationship to the “high” literature of the era, when critics such as Dwight MacDonald were intent on putting up walls to contain the spreading “ooze of Midcult?”

GO: I doubt that any of these writers would have been concerned with MacDonald’s strictures—they were each too busy exploring the ramifications of their particular and distinctly personal evolution.

These were all serious writers bent on surpassing themselves; I’m not aware that any of them looked on their chosen form as less than worthy.

As David Bordwell has discussed in his recent book Perplexing Plots, writers like Evan Hunter (aka Ed McBain), Donald Westlake (aka Richard Stark), Millar, and Highsmith were thorough and conscious formalists always in search of further refinements and variations. In The Fiend and The Tremor of Forgery, Millar and Highsmith push the crime novel into a zone of ambiguity where we wonder who is not a criminal or whether there has been any crime at all.

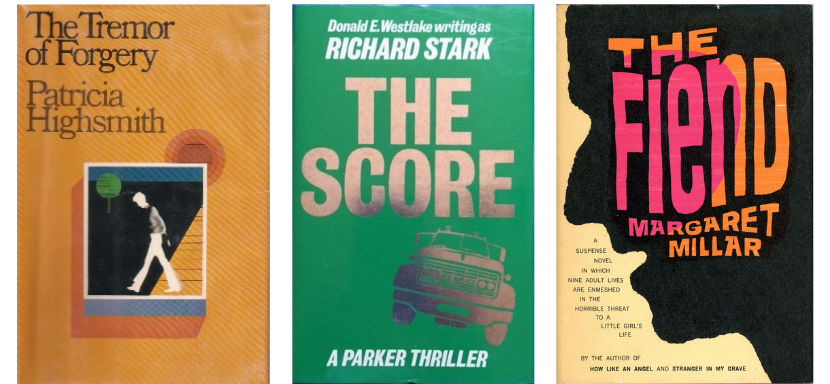

Covers of The Tremor of Forgery by Patricia Highsmith (Doubleday & Co., 1969), The Score by Richard Stark (first U.K. edition, Allison & Busby, 1985), and The Fiend by Margaret Millar (Random House, 1964)

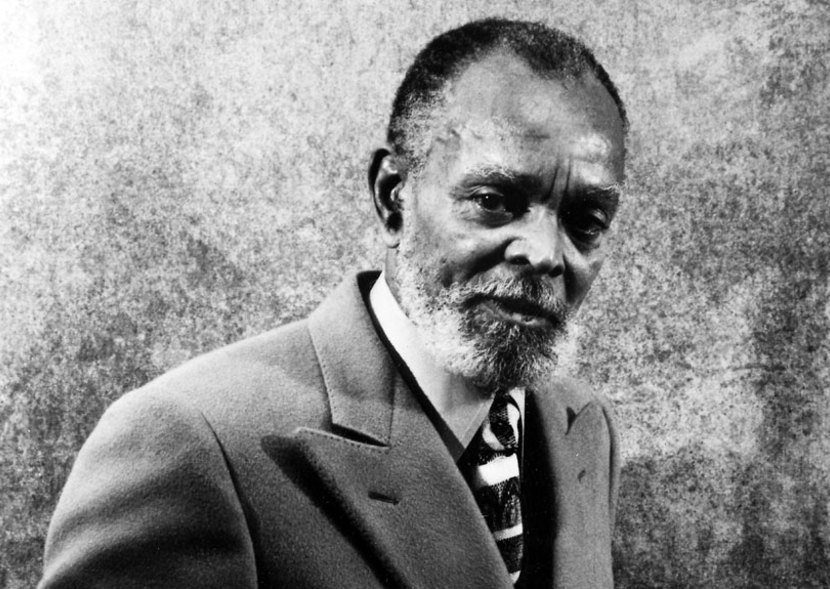

As for Himes, he commented on his freely inventive Série Noire novels, set in what he admitted was a Harlem of the imagination: “I took myself seriously as a writer of absurd stories and the Americans could go to hell.”

All of these writers were also perfectly aware that their audience encompassed a much wider variety of readers than that of most literary fiction.

Chester Himes, date unknown (Afro American Newspapers / Gado / Getty Images)

LOA: Psychological distress and emotional torment bedevil many of the novels’ protagonists, from the unnamed criminal at the center of Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death to the nihilistic, self-centered Willy Griff of Brown’s The Murderers. How does a conception of the interior and the irrational assert itself in ’60s crime fiction? How do these dark corners of the human mind come to be expressed via the conventions and subversions of genre?

GO: Mad killers, often with heavily underscored Freudian motivations, were already a standard feature of crime fiction in the 1940s, and heroes as well were often carrying a heavy freight of inner anguish.

In the ’50s, Jim Thompson, in novels like The Killer Inside Me and Savage Night, pushed things to extremes by writing whole books from the vantage point of a murderer. Brown’s The Murderers follows in this tradition but to very different effect, as the narrator Willie Griff assumes almost the tone of a stand-up comic with a dark sense of humor, as if his murderous activities were merely another aspect of his show-business ambitions.

Covers of The Name of the Game is Death by Dan J. Marlowe (Gold Medal Books, 1962) and The Murderers by Fredric Brown (E. P. Dutton & Co., 1961)

By contrast, Marlowe’s criminal hero in The Name of the Game Is Death offers a lucid self-analysis of his objectively brutal behavior. At the end of Millar’s The Fiend, everybody in the book seems to hover on the brink of one derangement or another, however much they may try to adhere to the norms of their suburban world.

Evan Hunter, aka Ed McBain, circa 1953 (Greenleaf Publishing)

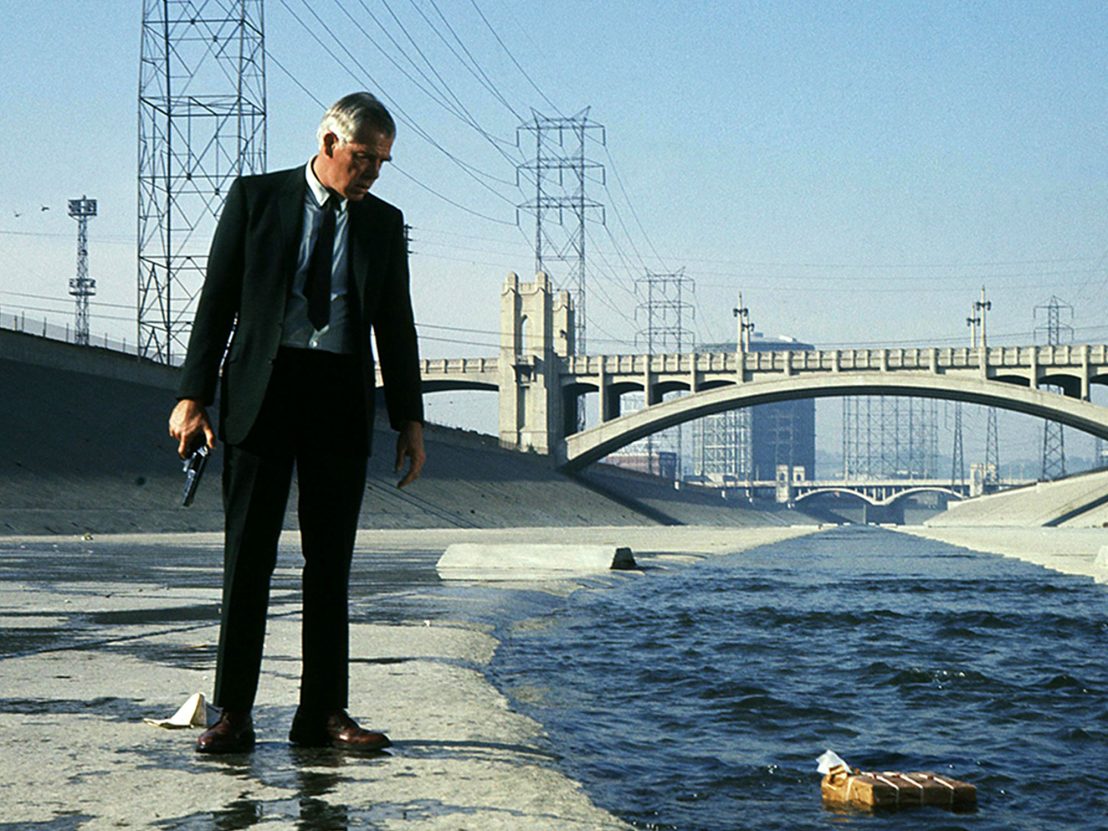

With McBain, taking the stance of big city cops exposed to every variety of madness and malevolence, and Stark, assuming the mindset of a relentlessly dedicated professional heist artist, we peer into an immense machine indifferent to the humans caught up in its workings; madness is not individual but societal.

Patricia Highsmith, 1962 (Harper & Brothers)

By the time we get to Highsmith’s The Tremor of Forgery, we’ve joined the absurdism of Camus or Beckett: “It was like becoming nothing and realizing that one was nothing anyway, ever.” The reader is led to identify with a protagonist who dissolves in the act of reading.

LOA: Though the concept of a crime thriller that’s simultaneously a work of literature doesn’t seem particularly farfetched today, writers plying the genre in the ’60s faced a transitional moment when old detective and noir conventions were growing stale and the eyes of readers were beginning to wander elsewhere, chiefly to science fiction, spy and secret agent stories, and fantasy. Did the authors in this collection consider themselves genre writers, first and foremost, even as they extended the category’s limits?

GO: These were all serious writers bent on surpassing themselves; I’m not aware that any of them looked on their chosen form as less than worthy. Himes wrote in many modes, and ultimately did not differentiate the crime novels from the rest of his oeuvre. Highsmith’s ambitions are clear from her journals, not to mention the literary allusions that abound in her novels. I do not think they thought in terms of limitations, but of artistic opportunities not otherwise available.

Certainly McBain and Stark were formal innovators who remained tirelessly and playfully experimental throughout their careers. Each case is different, of course. Marlowe was a late-blooming writer who operated on the fringe in more ways than one; he had a fairly successful career as a thriller writer, but never did anything better than The Name of the Game Is Death. Williams approached writing with the same respect for craft that he extended to his descriptions of boatbuilding and navigation in Dead Calm.

Still from the 1989 film adaptation of Dead Calm, starring Sam Neill, Nicole Kidman, and Billy Zane (Warner Bros.)

As for Hughes, who made her literary debut in the Yale Younger Poets series, it seems doubtful that she regarded the crime novels to which she devoted the rest of her writing life—books like Ride the Pink Horse, In a Lonely Place, and The Expendable Man—as any sort of betrayal.

LOA: Which novels in the collection are your favorites, and why? Did you discover any new voices or hidden gems while editing the volume?

Covers of Doll by Ed McBain (Delacorte Press, 1965) and Dead Calm by Charles Williams (Viking Press, 1963)

GO: The editing of these volumes was an extended process, and there were many discoveries along the way. I had not previously read The Fiend or Run Man Run, and each was a major surprise.

As for McBain, I went through a great many titles in the 87th Precinct series before deciding on Doll—he published thirteen of them in the 1960s and there were many other likely candidates. The whole fifty-four-volume series is an extraordinary exercise in what can be called pulp modernism.

As for The Tremor of Forgery, it has haunted me since I read it in the early ’70s. That said, I have reread The Score more than any of these books—the Donald Westlake/Richard Stark narrative machinery catches me in its gears every time.

Lee Marvin in Point Blank, a 1967 film adaptation of Richard Stark’s Parker novel The Hunter (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

Geoffrey O’Brien is a poet, a widely published critic, and the author of books on crime fiction, film, music, and cultural history, including Hardboiled America, The Phantom Empire, Sonata for Jukebox, Where Did Poetry Come From: Some Early Encounters, and Arabian Nights of 1934. He was for many years editor-in-chief of Library of America.