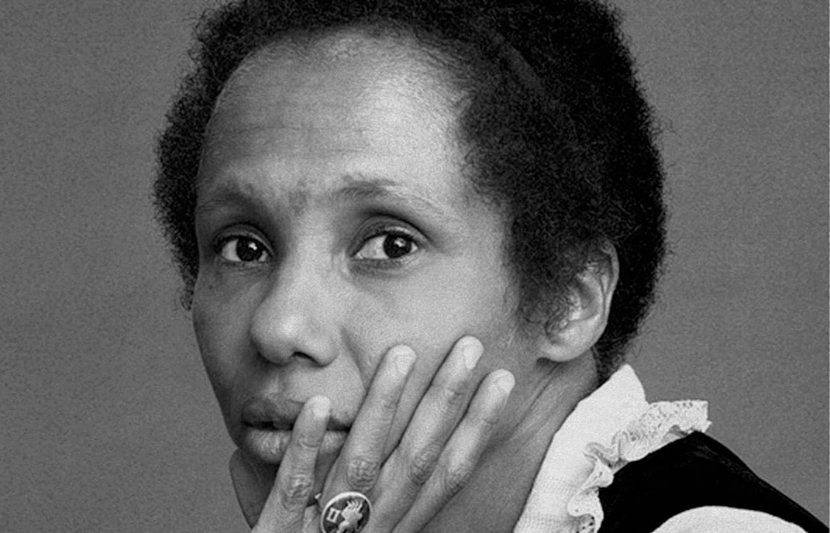

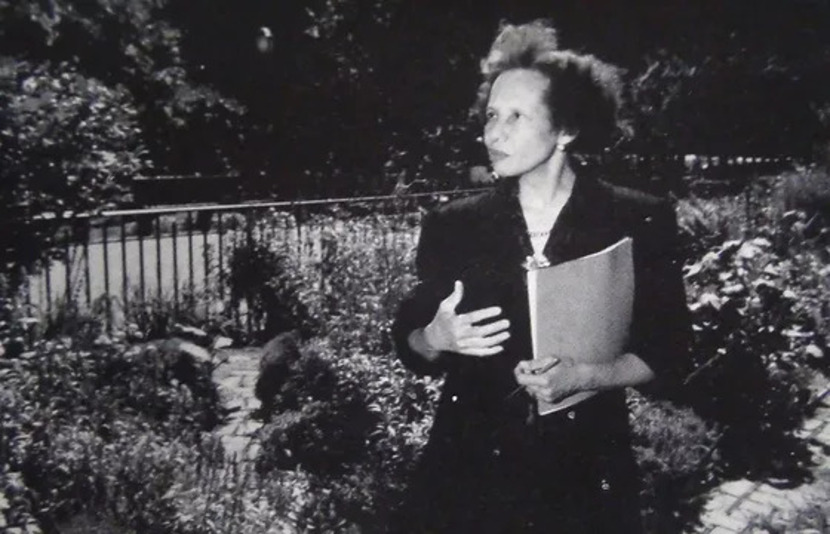

Radical in her artistic vision, fearless in her excavations of interior life, Adrienne Kennedy has for more than sixty years been one of America’s most daring and prodigious writers for the stage. In groundbreaking plays including her 1964 Obie Award–winning Funnyhouse of a Negro and 1991’s Ohio State Murders (belatedly staged on Broadway in 2022), Kennedy conjures a theatrical world that is by turns phantasmagoric, poetic, and achingly real, at once immersed in history—personal, political, cultural—and committed to the past’s ongoing reinterpretation and reinvention.

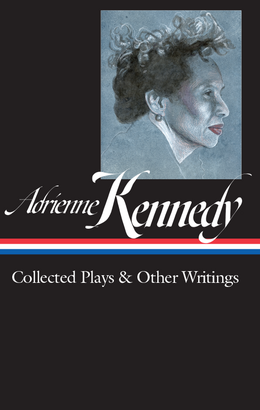

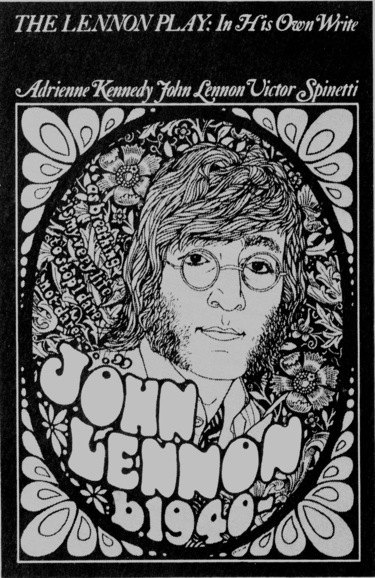

Coinciding with Kennedy’s ninety-second birthday this September, LOA’s publication of Adrienne Kennedy: Collected Plays & Other Writings, edited by Marc Robinson, serves as a fitting tribute to this nonpareil dramaturg and author. From her reality-warping one-acts The Owl Answers and A Lesson in Dead Language to her hair-raising examination of race and cinema in A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White and her searing indictment of police violence in Sleep Deprivation Chamber, Kennedy has resisted and remixed the conventions and formal constraints of the theater to the awe of actors, directors, and audiences alike.

Over e-mail, Robinson spoke to LOA about Kennedy’s emergence as a major writer in the 1960s and ’70s, the complex elision of movie star celebrity and personal autobiography that recurs throughout her work, and which pieces newcomers should seek out to get their first taste of the playwright that Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has said will still be winning fans “for centuries to come.”

LOA: Despite early encouragement from family members and mentors, Kennedy wrote for more than a decade—through marriage, the birth of two children, and a stint living abroad—before her first play was produced. How would you trace the genesis and development of her artistic vision, and what obstacles did she face in achieving it?

Marc Robinson: Kennedy was writing from an early age—she unsuccessfully submitted a story to Seventeen magazine as a teenager—but like many of her female peers in the 1950s, she was expected to become a schoolteacher, following in the footsteps of her mother. As an undergraduate at Ohio State University, after she had been discouraged from majoring in English (an injustice she recounts in Ohio State Murders), she majored in education. Right after graduating and getting married, she was living at her parents’ home in Cleveland, awaiting the birth of her first son while her husband was in Korea, and it was then that she wrote her first play, a lost work inspired by Elmer Rice’s Street Scene.

Tennessee Williams was an even greater influence: when Kennedy was sixteen, she saw a production of The Glass Menagerie in Cleveland, with the original Laura, Julie Haydon, in the cast. “That planted a big seed,” she once said. She has also traced her characters to the “hot little segregated town” of Montezuma, Georgia, where her grandparents lived.

Only after she moved to New York did she dedicate herself more fully to writing. Even then she had to negotiate the demands of parenthood and marriage—a struggle the playwright-character Clara describes in A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White. Kennedy took fiction-writing classes at Columbia and playwriting classes at the New School, among other places, and though she was encouraged by her teachers, none of these early efforts bore fruit.

All the while, Kennedy was reading voraciously and plunging into other forms of culture in the New York of the 1950s—immersing herself in novels, poetry, jazz concerts, movies, and art exhibitions. This had a far greater impact on her artistic development, I think, than any of her classes. Her prose works People Who Led to My Plays, “Theater Journal” (in Deadly Triplets), and “Paragraphs, Passages, and Pages That Changed My Life” are remarkable partly as records of this self-education.

Kennedy also lived abroad at the start and end of the 1960s, and has written that “the bride vanished” and the mature artist appeared only when she traveled to Ghana for her husband’s work (they lived there for several months in 1960 and 1961).

Funnyhouse of a Negro, her first produced play, owes much (she has said) to Accra’s light, heat, nearby savannas, and “sweet-smelling frangipani shrubs.” Travel also dislodged from her imagination other crucial early works. The Owl Answers—finished along with Funnyhouse in Rome (a setting she revisits in A Lesson in Dead Language)—recalls her first visit to London. The imagery of A Rat’s Mass came to her as she rode a train from Paris to Rome. She finished the story “Because the King of France,” her first published work, on an ocean liner during her first Atlantic crossing.

I hope, now that many of Kennedy’s hitherto unpublished plays are available, it will be harder to categorize her, that this volume will encourage scholars to complicate their earlier conclusions about her artistry.

Already committed to her aesthetic vision when she returned to New York, she enrolled in Edward Albee’s workshop at Circle in the Square. But it would be misleading to think, as some do, that Funnyhouse emerged from the workshop. Kennedy had submitted the complete manuscript as her application, and Albee himself once said he merely “refereed” rather than taught the enrolled writers. But the experience did allow Kennedy to see her work staged for the first time—and her conversations with Albee and her director Michael Kahn gave her more courage to pursue her instincts. Albee’s support would be crucial even years later: Kennedy remembers that his advocacy played a role in the Signature Theatre’s decision to dedicate its 1995–96 season to her work.

LOA: Kennedy is sometimes considered part of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, yet her long, varied career resists neat categorization. What was her relationship to her artistic peers and wider creative communities? Did she consider herself part of a broader scene or circle?

MR: It’s hard to place Kennedy in any particular artistic school or movement, and even though each of her 31 published plays unmistakably bears her signature, she explored so many genres over sixty-plus years as to defy any attempt to generalize about her. For a reader paging through this new edition, it’s thrilling, and instructive, to observe her seeking the right form for her many aesthetic, social, and emotional commitments—and in the process challenging us to rethink what counts as a play.

She is stylistically restless—experimental in the fullest sense—not for its own sake but to do justice to both her psychic and creative selves, and to her evolving idea of what theater can be. The Kennedy of A Rat’s Mass or A Beast Story—expressionist and nonlinear plays, populated with hybrid animal-human figures, full of nightmarish imagery—is very distant from the Kennedy of, say, A Lancashire Lad, a rousing, often sunny musical based on Charlie Chaplin’s autobiography. And those three works are distinct from Boats, a two-page arrangement of poetic language, movement, and modulating colors, and the suspenseful, plot-driven Ohio State Murders. I hope, now that many of Kennedy’s hitherto unpublished plays are available, it will be harder to categorize her, that this volume will encourage scholars to complicate their earlier conclusions about her artistry.

Kennedy’s relationship to the Black Arts Movement is especially complex. She was personally close to several members of the movement—among them Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones, whose play Dutchman premiered the same year as Funnyhouse of a Negro) and Ed Bullins (who called Kennedy “the revolution”). But, as others have pointed out, her allusive, interior work was out of step with the movement’s dominant styles and strategies. “I don’t write to any special person,” she told an interviewer in 1978. There is also a simpler reason for her outlier status: “People wanted me to be part of the movement,” she said, “but, frankly, I was always at home with my children.”

Kennedy, however, is not a solitary figure, though she preserves her critical distance from established genres and well-worn styles (including experimental ones) and the surrogates in her plays often stand outside the gates of a culture they revere. In 1972, she helped found the New York Theater Strategy (a playwright-directed producing organization) and the Women’s Theater Council. She served in a leadership role at PEN. Her thirty-year teaching career inspired countless younger writers.

More specifically, we should dispense with the idea that Kennedy is so hermetic or sui generis as to be unengaged with the era’s politics. Of course, much of her work deals with racism, obliquely or directly, usually as it oppresses a central character not unlike herself. But in some pieces, she addresses herself even more directly to the public sphere’s pressing issues and political figures. She rails against racist police brutality in Sleep Deprivation Chamber, weighs the legacy of Frantz Fanon in the Alexander Plays, and tracks the wider fight against African colonialism in the prose work “The Bride Vanished.” Some of her most challenging and abstract plays take on greater clarity when you know the social context she had in mind while writing them.

LOA: Film, movie stars, and celebrity are recurrent themes in Kennedy’s work (in her memoir, she writes that she once dreamed of becoming a famous actor before scrapping that ambition to focus on writing). What does the glamorous world of Hollywood cinema signify to Kennedy? How does she transform or reimagine it in her plays?

MR: Kennedy’s knowledge of film is profound. She puts that expertise to surprising uses, going beyond mere devotion to subtle critique, even as she and her protagonists are happily enthralled by the screen and unapologetic in their loyalties. The reverence is double-edged—the fans in her plays and prose (including herself) are never unaware of their distance from the cinematic worlds that mesmerize them. They nonetheless aim to close it.

Kennedy once recalled how, in her diverse Cleveland neighborhood in the 1940s, Modern Screen magazine helped forge alliances across ethnic and racial divides: Italian, Polish, and Black children passed around each new issue and reenacted favorite movie scenes in their backyards. That memory lies behind A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White, in which Clara, the Black protagonist, recruits the white leading actors from Now, Voyager, Viva Zapata!, and A Place in the Sun to share her psychological burdens. The movie characters’ stories of shame, frustrated desire, and suffocating families mirror Clara’s own; they also free her to pursue a life in writing.

Movie theaters, too, are charged with meaning in the plays. Mysterious, troubling events unfold at the Pathé newsreel theater in Hitler’s Addendum. The fabled Thalia and New Yorker theaters, now closed, had been refuges for the ambiguously menaced protagonist of Etta and Ella on the Upper West Side.

Kennedy is also interested in how her relationship to the movies, and the needs she hopes they’ll satisfy, have changed over time. In a fascinating interview with the film curator Thomas Beard, she speaks of how she moved past her childhood habit of measuring herself against movie stars. As she became an artist herself, she began to emulate movie directors instead (many of whom worked far from Hollywood).

“I wanted to create like L’Avventura,” she said, speaking of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 film. “I was now studying the images of [Fellini’s] La Strada. I felt I was studying the world. I felt I was studying a society, something impossible in Notorious, Suspicion, The Lady Vanishes; the society was there, but I saw only the stories. No more buying spectator pumps because Bette Davis wore them in Now, Voyager. No more trying to do my hair like Paula in Gaslight. I wanted to know what Visconti thought of nineteenth-century Italy, what Rossellini thought of postwar Italy. . . . I know when I see [Bergman’s] Wild Strawberries I am learning how to compose my disparate memories.”

LOA: Photographs and found imagery appear throughout Kennedy’s writing, from the play Cities in Bézique to her memoir People Who Led to My Plays. What explains this unique component of Kennedy’s work, so unusual in playwriting, and how do these pictures function in her texts?

MR: This, to me, is the most exciting aspect of Kennedy’s theater. She is as innovative a visual artist as a playwright: an artist’s sense of pattern, spatial relationship, and visual rhythm informs her theatricality. In this regard, she is fulfilling a famous demand of her beloved Tennessee Williams for “a new, plastic theater” (as he called it in a note to The Glass Menagerie). She assembles her plays rather than simply writes them, creating what the scholar Ross Posnock has called “cosmopolitan collage.”

Her materials are often textual—theatrical, literary, or sub-literary. A character reads aloud from Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles in Ohio State Murders, for instance, and several characters enact a scene from the medieval York cycle in Motherhood 2000. Sleep Deprivation Chamber draws on deposition or trial transcripts.

But Kennedy also thinks of collage visually—it’s a form that has interested her ever since she was a girl poring over her mother’s 1920s college scrapbook and pasting photographs and clippings in her own scrapbook of 1940s movie stars. “My Movie. Star. Scrapbook. My. Mother’s scrapbook,” Kennedy once wrote, using her characteristically telegraphic e-mail style to turn words into images and sentences into collages. “All these things. Are. My. Writing. . . . They. All. Go. Together.”

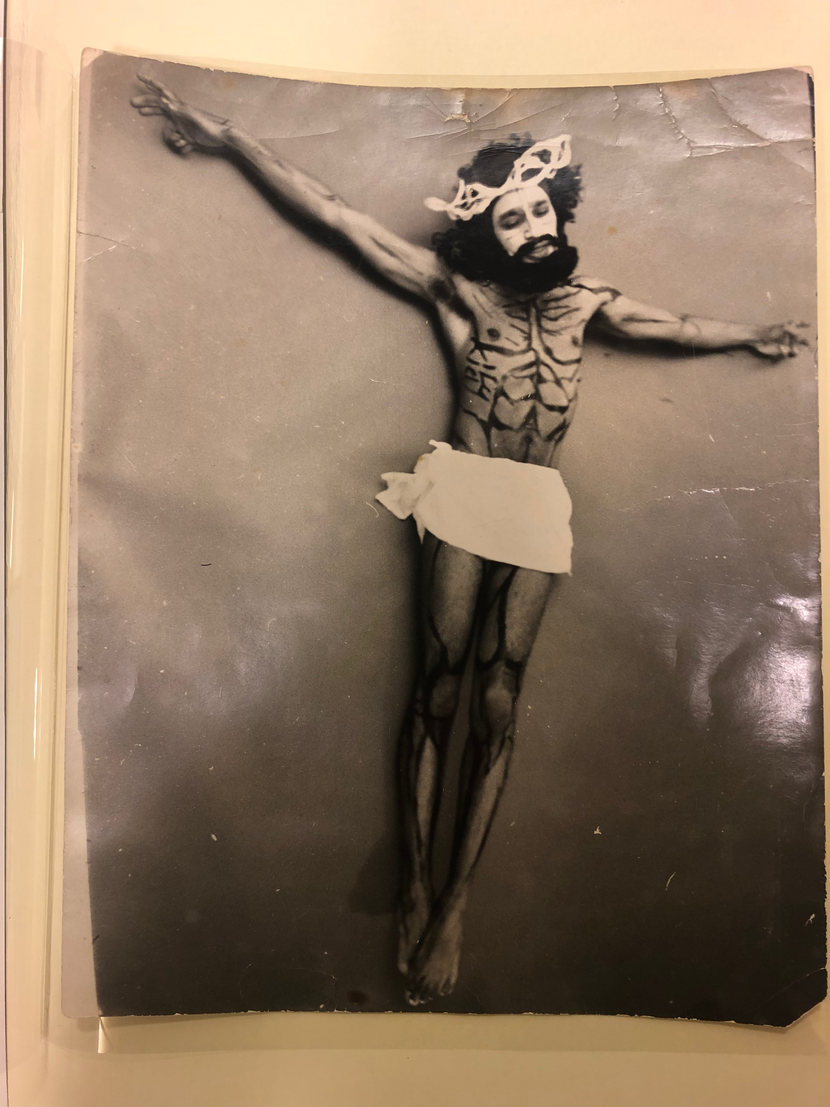

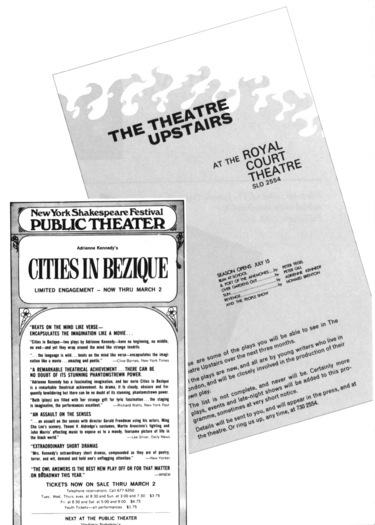

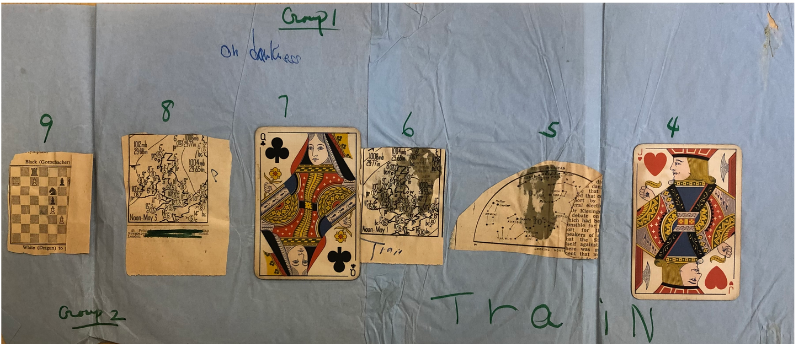

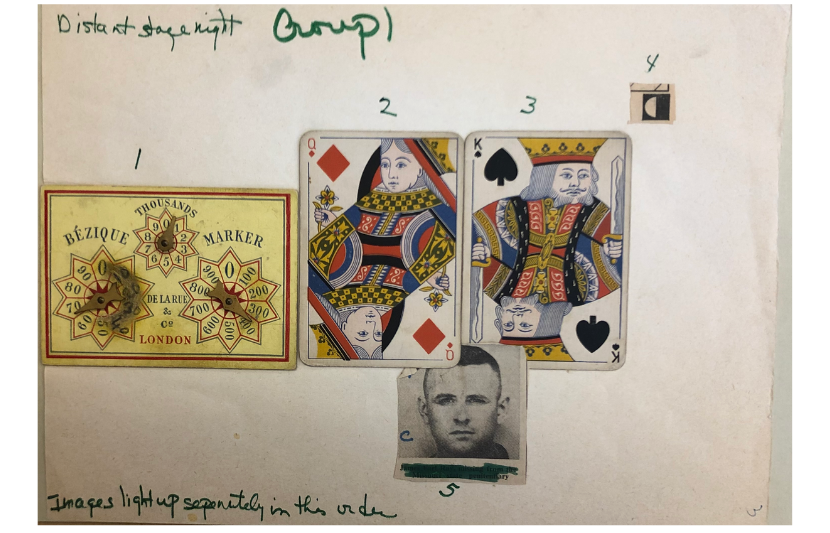

Almost from the start of her career, she incorporated mass-culture iconography, personal photographs, and found images into several plays and prose works. Cities in Bézique even includes other objects: playing cards and a Bézique scoring device, along with a film still, astronomical charts and weather maps, and newspaper photos of Coretta Scott King, Yolanda King, and others.

Even when she’s quoting texts, she is thinking of those passages as objects first—pages cut out from books to be layered on the surface of her own pages. During the first year of Covid, when many of us were locked down, she took this approach to the logical next step, collaborating with one of her grandsons to create a photographic series she called “Cherished Objects from the Past.” The composition of her handwritten captions joined to images of furnishings from her home, jewelry and clothing, and other mementos, expands the definition of writing even further.

The archived manuscript of her 1973 play, An Evening with Dead Essex, exemplifies Kennedy’s approach. The author’s credit line originally read “Material arranged by Adrienne Kennedy.” That wording makes overt her curatorial idea of playwriting. Rather than simply invent a new world, she re-sees and reforms the existing one—or, more precisely, looks critically at how others have seen it.

In many works Kennedy turns the entire stage into a surface for collage.

Dead Essex examines how journalists covered a politically charged event: the tragedy of Mark Essex, a Black ex-Navy seaman who, in January 1973, killed nine people in New Orleans before being shot by police. On many manuscript pages, Kennedy glued or taped articles from The New York Times, the New York Post, Newsweek, and other publications—reports from which her characters read aloud. Other manuscript pages include newspaper photographs of Essex as a boy and his New Orleans apartment, or widely disseminated images of the Vietnam War, or graphics of B-52 bombers and ads for Bergdorf Goodman. Per Kennedy’s wishes, they’re not published with the text, but I think it’s important for us to recover the scene of Kennedy encountering, clipping, and refashioning them—to imagine her resisting, or at least questioning and complicating, the ways the media initially shaped her understanding of the event.

In many works Kennedy turns the entire stage into a surface for collage. To look at a play’s set, in these instances, is to be reminded of her wide reading, viewing, and collecting, her sifting through private and public archives, before she drafted a manuscript.

In Funnyhouse of a Negro, the character Sarah (a Kennedy-like writer who says she is “preoccupied with the placement and geometric position of words on paper”) decorates her room with photographs of castles, Roman ruins, and English monarchs. The action of Black Children’s Day, a play set in a history museum, unfolds against a photographic exhibit of World War II aircraft; a “film of fragmented pictures” of clocks, mirrors, and bureaus; a mural in “violent abstract lines”; and five “realistic, historically accurate” painted panels depicting American Black life from the 1840s to the 1940s. She Talks to Beethoven is filled with drawings, wedding portraits, X-rays, a mural about Ghana’s independence, and a photograph of its first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Pictures of London neighborhoods and landmarks in the 1960s, and of Kennedy’s sons, are projected in Mom, How Did You Meet the Beatles? By the time Kennedy presented He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box, in 2018, she was directly emulating a scrapbook’s composition. One character’s dressing-room mirror and a storeroom wall are larger-than-life album pages, layered with pictures of Berlin, London, and Georgia, and of Roosevelt, Dylan Thomas, and the Invisible Man. The stage containing them is an opened book.

In all these works, Kennedy is interested in more than just the subjects of those pictures—the family members, movie stars, writers, politicians, or other public figures. She also considers how their representations have taken hold of our imaginations. For her, and for her characters, the widely circulated (or privately cherished) images are repositories for the emotions aroused by their subjects. They give shape to what might be amorphous and anchor what might be ephemeral.

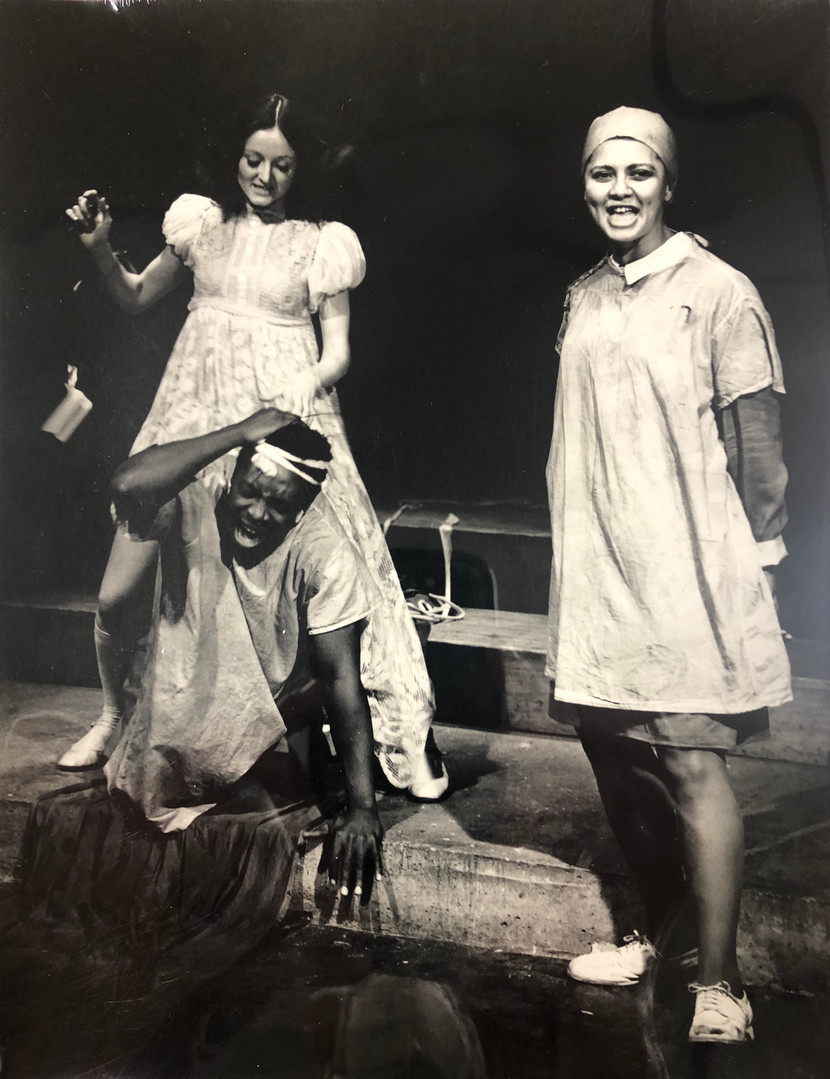

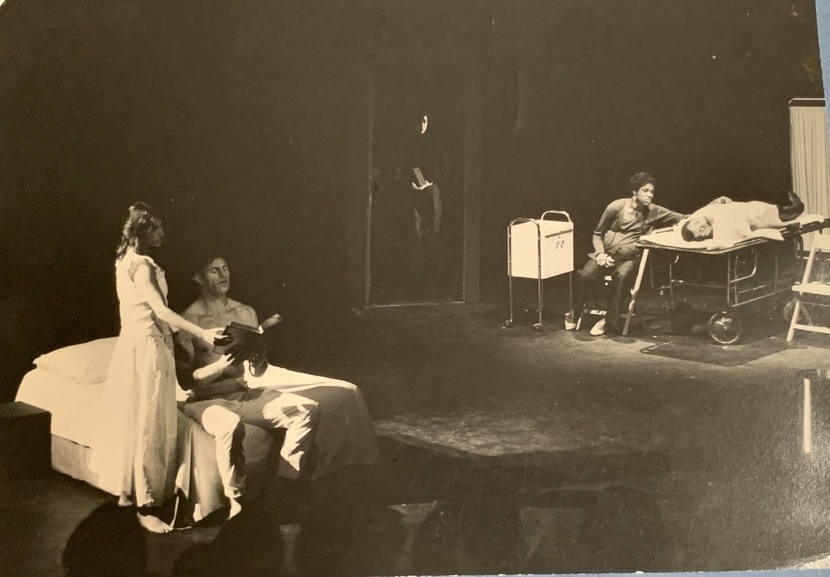

LOA: Kennedy’s writing is sometimes called difficult to perform or challenging for audiences to engage with. Which of her works would you encourage newcomers to explore first? Can you describe any memorable productions or performances of Kennedy’s plays?

MR: It’s true that Kennedy’s plays pose particular challenges for readers, even for readers used to staging scripts in their minds. Kennedy’s understanding of space and time, and of the power of juxtaposition and rhythm, is highly sophisticated. For her, stage lighting—bursts of blinding light, sudden darkness, vibrating shadows—can be as active and expressive as the actors are. She also exploits the expressive potential of silence, stillness, and repetition. Her stage directions offer essential instructions about tempo, color, syncopation. Readers shouldn’t simply attend to what characters say or do; how they speak and move is just as revealing.

Kennedy’s first-time readers might start with Ohio State Murders, the play that was produced on Broadway in 2022, more than thirty years after it was written. It combines many of her compositional innovations with a fast-moving, enthralling plot. The play’s nightmarish memories swirl around a central character who works to manage them with the structure of narrative itself: it’s a story about storytelling. It’s also, despite the complexity of its events and the motives behind them, relatively austere, in the best sense: Kennedy knows that minimalist stage pictures can distill entire psychological worlds.

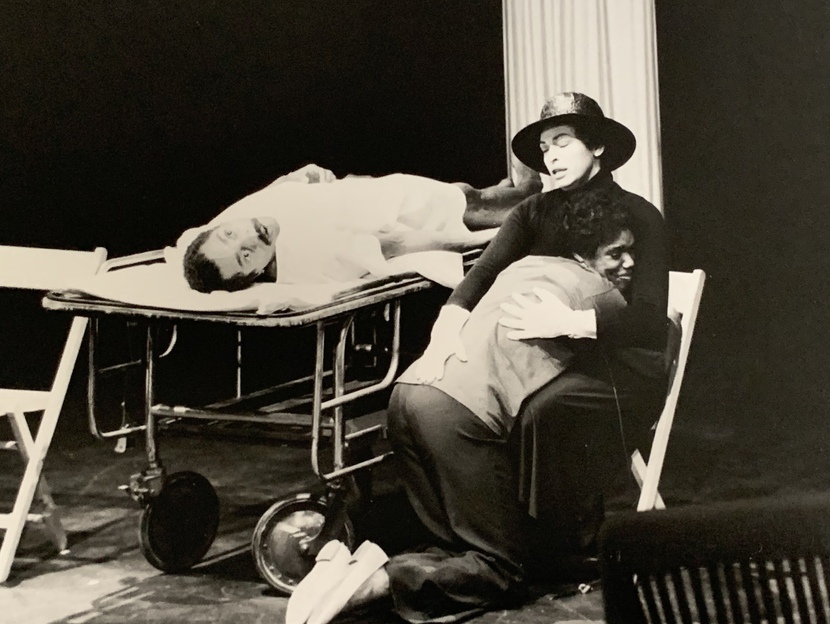

I was lucky to see a workshop of Gerald Freedman’s original production of it, in 1991, and I’ll never forget the central image: a window high up in the soaring proscenium, through which we could see snow silently falling; it dwarfed the actress standing many feet below, making her seem especially vulnerable and alone.

The premiere production of He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box, directed by Evan Yionoulis and designed by Christopher Barreca, was also anchored by a powerful scenic element: a long, steep staircase that plunged down the middle of the stage toward the audience. Whenever the actors Juliana Canfield and Tom Pecinka carefully walked up or down it, you could see how precarious their relationship and well-being were.

In 1995, Joseph Chaikin remounted his original production of A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White—another play I’d urge upon Kennedy newcomers. The clarity and control he brought to the text helped us track overlapping narrative lines. We could distinguish among the merging worlds of three Hollywood films, the protagonist’s memories, and an immediate crisis unfolding in the play’s present tense. (Speaking of the 1976 production, Kennedy admired how it “never stopped moving,” like the movies it drew upon.)

In 2016, the director Lila Neugebauer did extraordinary things with Funnyhouse of a Negro, Kennedy’s best-known play and one of the essential works of American drama. The lighting was shadowy, the soundscape was clangorous, the stage was like an open grave. This production did full justice to the psychological vortex that Kennedy envisioned.

But anyone who loves Kennedy’s work lives in a constant state of longing, for her plays are not produced often enough! There are legendary productions that came and went too quickly. I wish I could have seen the much-admired Ellen Holly in Michael Kahn’s original staging of The Owl Answers (it appeared only on two separate days in 1965), or any of the productions that starred the late Robbie McCauley, or the premiere of A Lesson in Dead Language, with a set apparently designed by the avant-garde filmmaker and theater artist Jack Smith!

The play I am most eager to see is one that has never been staged. Joseph Papp had commissioned Cities in Bézique for the Public Theater, but when Gerald Freedman expressed reservations about its viability, he decided against producing it—a pity, since it’s one of the most radical American plays I’ve read.

Freedman, despite his doubts, recognized its daring. In a 1968 letter to Papp about how it could be staged, he saw that Kennedy, as usual, was ahead of her time. “If one wanted to present this, I believe the best possible way would be for a single view[er] [looking] into a black box with an illuminated screen at one end. A more public way might be a small audience each isolated by wearing earphones and viewing slides in a darkened room.”

I’d go to that in a heartbeat!

Marc Robinson is Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of Theater & Performance Studies and English at Yale University. He is the author or editor of numerous books, including The American Play: 1787–2000.