The following remarks were given by Farah Jasmine Griffin at LOA’s 40th anniversary gala reception on May 1, 2023. For more on the event, including videos, photos, and transcripts of featured speeches, click here.

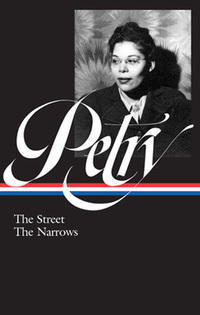

I had the pleasure of editing the Ann Petry Library of America volume, and I jumped at the opportunity because I am a Petry evangelist. She remains one of my favorite authors, and she is, I believe, one of the best writers our nation has produced and yet one who remains little known. She’s constantly discovered and rediscovered. So, the chance to introduce her to a broader readership and to secure her place and stature in our literary history continues to be of utmost importance to me.

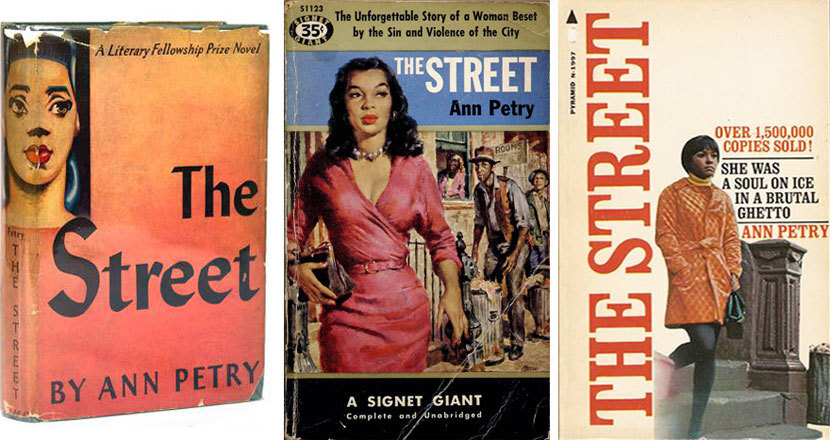

The publication of her first novel, The Street, in 1946, brought critical acclaim and a degree of literary celebrity. It’s set in wartime Harlem. It’s her most famous novel, the most famous novel of an unfamous writer. It’s the story of Lutie Johnson, a beautiful single mother who strives to leave domestic service for more lucrative employment. Her idea of success is inspired by Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, by an Italian immigrant shopkeeper, and her wealthy white employers, all of whom encourage her to work hard, save money, and create a better life for herself in the quote unquote “best country in the world.”

But each of these mentors unfortunately fails to warn her of the pitfalls and the obstacles that await her as a working-class Black woman in a pre–Brown v. Board of Education America and a Jim Crow America. She is under surveillance constantly by a predatory neighbor. She is stalked by her building superintendent. She is watched, cultivated, and trapped like prey by the owner of her apartment building, who also owns the club where she hopes to work. She has nowhere to run, nowhere to hide.

The Street became the first novel by a Black woman to sell more than a million copies. It was always in print; it never went out of print. It was published in several paperback editions, translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, German. Its author appeared on magazine covers, in glossy feature articles. But just as her literary celebrity grew, the specter of the second Red Scare began to rise, and Petry and her husband returned to Petry’s hometown of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, in 1947.

They purchased a home and she avoided celebrity, avoided publicity except as it directly related to her writing. Some of this insistence on her privacy came from a desire to protect herself, but also, I think, because her New York years had been filled with leftist friends and colleagues and she despised the kind of anticommunist fervor that swept the nation in the 1950s, although she had never been a member of the Communist Party. She actually was a member of the Republican Party, as were many African Americans prior to Roosevelt, because it was the party of Lincoln.

She was openly supportive of Paul Robeson. And her third novel, 1953’s The Narrows—which I think is her most ambitious novel, set in a small Connecticut city and collected in the Library of America volume—courageously articulates her disdain for McCarthyism, which, the protagonist says, “hunts both communists and Negroes.”

The Narrows is ostensibly the story of a tragic love affair between the married Camilla Sheffield—a white socialite and heiress, daughter of the town’s wealthiest family and heir to the Treadway Munitions fortune—and Link Williams, a kind of Robeson-esque figure, a scholar-athlete who is a graduate of Dartmouth and a beloved son of the town’s Black community, known as the Narrows. When Link tries to end their relationship, Camilla falsely accuses him of rape. He is arrested, released on bail, but eventually kidnapped and murdered by Camilla’s husband and mother.

Now, the narrative is driven forward by this love affair. It’s what makes people want to read it. It’s a very cinematic story. But actually, the novel just uses the relationship as a vehicle for Petry to force a confrontation between a number of opposing elements within the narrative—yes, most obviously between Black and white, but even more importantly, between different classes of people. It offers a critique of racism, but also a stinging critique of class, and especially market-driven society’s impact on the press, on the police, and most importantly on an individual’s conception of themselves.

She refused to reveal her personal life to reporters and to scholars alike, believing that if she had to choose, she would choose to be known as a writer and not as a celebrity. She felt that these concepts were fundamentally incompatible to her.

The Narrows is an eloquent statement of both Petry’s antiracist and anti-capitalist politics. Furthermore, the interracial relationship at the novel’s center is an exploration of only one form of taboo sexuality. The Narrows also presents us with an openly gay character, a kind of explicitly homosexual relationship. There are also women who are openly sexual here, both Black women and white women. She explores a kind of multidimensional sense of sexuality.

All these elements landed the book on the list of banned books—yes, this also was a time of banned books—for the National Organization for Decent Literature, which was called the NODL. In 1956, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a statement on censorship activity by private organizations and it noted that the NODL was the most prominent, influential, and successful of a number of organizations engaged in censorship activity. Petry was one of 160 prominent writers who signed a statement against book-banning and censorship at the time.

So, all of this is the context in which her novels came out, but I think it’s also the context in which she retreated. It’s a context in which she didn’t want to be publicly known for anything other than her writing. That sort of privacy, I think, is nurtured by her own sensibilities. She refused to reveal her personal life to reporters and to scholars alike, believing that if she had to choose, she would choose to be known as a writer and not as a celebrity. She felt that these concepts were fundamentally incompatible to her. She described the hoopla that surrounded the publication of The Street as turning her into public property. And that phrase pops up again and again in her private writings.

As late as 1996, a half century after her first novel appeared, she told an interviewer—and this quotation, I think, is so meaningful:

Continuous public exposure, though it may make you a “personality,” can diminish you as a person. To be a willing accomplice to the invasion of your own privacy puts a low price on its worth. The creative processes are, or should be, essentially secret, and although naked flesh is now an open commodity, the naked spirit should have sanctuary.

This is a quotation that I return to, and it seems so foreign in our day and time, when there is such a desire to be a celebrity, especially with social media where everyone seeks the limelight. And yet I cannot help to think that there is wisdom in it—if in fact it might be one of the reasons that we know so little of Petry, requiring her to be discovered again and again.

But I think that Petry’s writing is as much a source of this kind of wisdom as it is for beauty, which is why I’m so grateful that we have this volume. It’s for this reason that I return to her again and again. If you haven’t read her, I invite you to do so.

Farah Jasmine Griffin is the William B. Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature and African American Studies at Columbia University, where she served as the inaugural Chair of African American and African Diaspora Studies. Her nine books include, most recently, Read Until You Understand: The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature and In Search of a Beautiful Freedom: New and Selected Essays. For Library of America, she has edited a volume of novels by Ann Petry.