The following remarks were given by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., at LOA’s 40th anniversary gala reception on May 1, 2023. For more on the event, including videos, photos, and transcripts of featured speeches, click here.

Why can I say that there is an African American literary tradition? Is it because the writers are all Black? Well, that doesn’t seem to be a sufficient definition. What if there were a formal principle that connects texts into a tradition so that there is a process of reading and revision, like links in a chain—a chain of signification.

I want to give you an example of how one of them works.

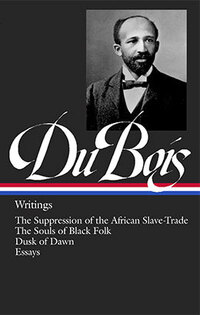

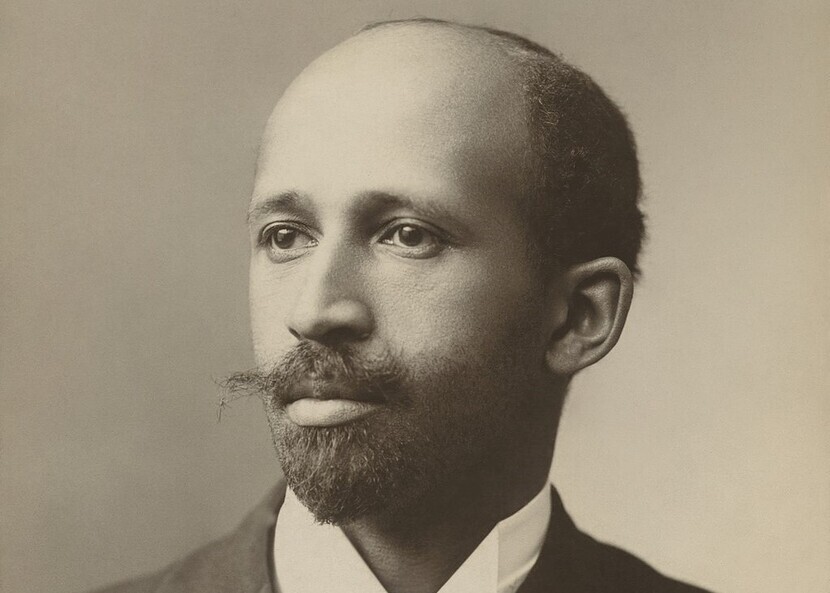

Probably the most famous paragraph in the history of African American literature was published in 1903 by the great W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black man to get a PhD from Harvard University, in 1895. In The Souls of Black Folk, the Bible for Black intellectuals, he says:

After the Egyptian and the Indian, the Greek and the Roman, the Teuton and the Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.

Now, obviously, for Du Bois, this double consciousness is a problem. And it’s a problem that’s produced by Jim Crow segregation. Remember, he publishes this in 1903. So, the cure for Du Bois—the cure for this double consciousness, this sense of alienation from oneself, if you’re Black—would be the end of segregation.

The key was to learn how to name one’s multiple identities and then to move seamlessly between one’s multiple identities.

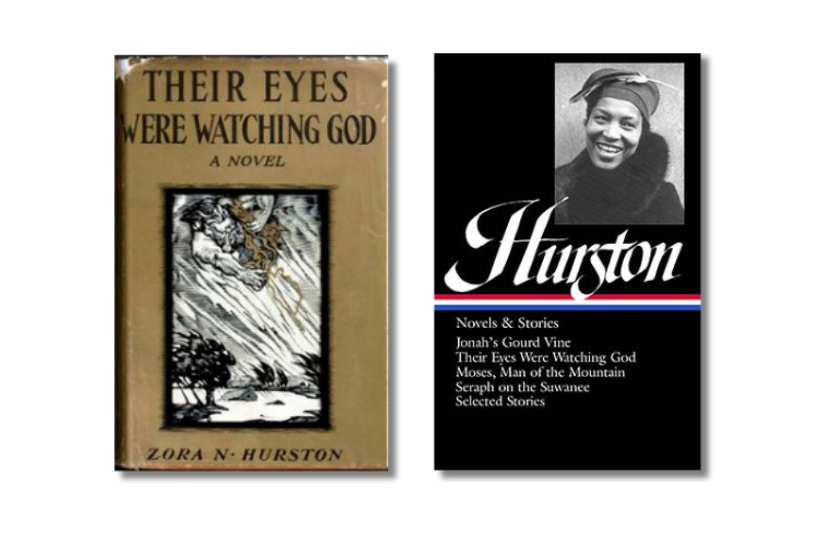

Funny thing happens in the life of a trope: it goes where it wants to go. For subsequent Black writers, particularly the one that I’m featuring tonight, Zora Neale Hurston, the trope of double consciousness is not a problem, but a solution. She realized that what Du Bois was describing was the condition of modernity itself, that we all have multiple identities. And the key was to learn how to name one’s multiple identities and then to move seamlessly between one’s multiple identities.

Hurston uses this as a structuring principle for her great novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, which is about the liberation of a woman who is being oppressed by a series of men. So, I’m going to let her explain to you how she flips Du Bois’s trope upside down, and we’re going to walk with Janie while she frees herself:

“You sho loves to tell me whut to do, but Ah can’t tell you nothin’ Ah see!”“Dat’s ’cause you need tellin’,” he rejoined hotly. “It would be pitiful if Ah didn’t. Somebody got to think for women and chillun and chickens and cows. I god, they sho don’t think none theirselves.”

“Ah knows uh few things, and womenfolks thinks sometimes too!”

“Aw naw they don’t. They just think they’s thinkin’. When Ah see one thing Ah understands ten. You see ten things and don’t understand one.”

Times and scenes like that put Janie to thinking about the inside state of her marriage. Time came when she fought back with her tongue as best she could, but it didn’t do her any good. It just made Joe do more. He wanted her submission and he’d keep on fighting until he felt he had it.

So gradually, she pressed her teeth together and learned to hush. The spirit of the marriage left the bedroom and took to living in the parlor. It was there to shake hands whenever company came to visit, but it never went back inside the bedroom again. So she put something in there to represent the spirit like a Virgin Mary image in a church. The bed was no longer a daisy-field for her and Joe to play in. It was a place where she went and laid down when she was sleepy and tired.

She wasn’t petal-open anymore with him. She was twenty-four and seven years married when she knew. She found that out one day when he slapped her face in the kitchen. It happened over one of those dinners that chasten all women sometimes. They plan and they fix and they do, and then some kitchen-dwelling fiend slips a scorchy, soggy, tasteless mess into their pots and pans. Janie was a good cook, and Joe had looked forward to his dinner as a refuge from other things. So when the bread didn’t rise, and the fish wasn’t quite done at the bone, and the rice was scorched, he slapped Janie until she had a ringing sound in her ears and told her about her brains before he stalked on back to the store.

Janie stood where he left her for unmeasured time and thought. She stood there until something fell off the shelf inside her. Then she went inside there to see what it was. It was her image of Jody tumbled down and shattered. But looking at it she saw that it never was the flesh and blood figure of her dreams. Just something she had grabbed up to drape her dreams over. In a way she turned her back upon the image where it lay and looked further. She had no more blossomy openings dusting pollen over her man, neither any glistening young fruit where the petals used to be. She found that she had a host of thoughts she had never expressed to him, and numerous emotions she had never let Jody know about. Things packed up and put away in parts of her heart where he could never find them. She was saving up feelings for some man she had never seen. She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them.

She bathed and put on a fresh dress and head kerchief and went on to the store before Jody had time to send for her. That was a bow to the outside of things.

So, now she can navigate and move seamlessly between these selves, the inside and the outside. And this is a killer. This is how she slays the man who has been oppressing her and finds her liberation:

It got to be terrible in the store. The more his back ached and his muscle dissolved into fat and the fat melted off his bones, the more fractious he became with Janie. Especially in the store. The more people in there the more ridicule he poured over her body to point attention away from his own. So one day Steve Mixon wanted some chewing tobacco and Janie cut it wrong. She hated that tobacco knife anyway. It worked very stiff. She fumbled with the thing and cut way away from the mark. Mixon didn’t mind. He held it up for a joke to tease Janie a little.“Looka heah, Brother Mayor, whut yo’ wife done took and done.” It was cut comical, so everybody laughed at it. “Uh woman and uh knife—no kind of uh knife, don’t b’long tuhgether.” There was some more good-natured laughter at the expense of women.

Jody didn’t laugh. He hurried across from the post office side and took the plug of tobacco away from Mixon and cut it again. Cut it exactly on the mark and glared at Janie.

“I god amighty! A woman stay round uh store till she get old as Methusalem and still can’t cut a little thing like a plug of tobacco! Don’t stand dere rollin’ yo’ pop eyes at me wid yo’ rump hangin’ nearly to yo’ knees!”

A big laugh started off in the store but people got to thinking and stopped. It was funny if you looked at it right quick, but it got pitiful if you thought about it awhile. It was like somebody snatched off part of a woman’s clothes while she wasn’t looking and the streets were crowded. Then too, Janie took the middle of the floor to talk right into Jody’s face, and that was something that hadn’t been done before.

“Stop mixin’ up mah doings wid mah looks, Jody. When you git through tellin’ me how tuh cut uh plug uh tobacco, then you kin tell me whether mah behind is on straight or not.”

“Wha—whut’s dat you say, Janie? You must be out yo’ head.”

“Naw, Ah ain’t outa mah head neither.”

“You must be. Talkin’ any such language as dat.”

“You de one started talkin’ under people’s clothes. Not me.”

“Whut’s de matter wid you, nohow? You ain’t no young girl to be gettin’ all insulted ’bout yo’ looks. You ain’t no young courtin’ gal. You’se uh ole woman, nearly forty.”

“Yeah, Ah’m nearly forty and you’se already fifty. How come you can’t talk about dat sometimes instead of always pointin’ at me?”

“ ’Tain’t no use in gettin’ all mad, Janie, ’cause Ah mention you ain’t no young gal no mo’. Nobody in heah ain’t lookin’ for no wife outa yuh. Old as you is.”

“Naw, Ah ain’t no young gal no mo’ but den Ah ain’t no old woman neither. Ah reckon Ah looks mah age too. But Ah’m uh woman every inch of me, and Ah know it. Dat’s uh whole lot more’n you kin say. You big-bellies round here and put out a lot of brag, but ’tain’t nothin’ to it but yo’ big voice. Humph! Talkin’ ’bout me lookin’ old! When you pull down yo’ britches, you look lak de change uh life.”

“Great God from Zion!” Sam Watson gasped. “Y’all really playin’ de dozens tuhnight.”

“Wha—whut’s dat you said?” Joe challenged, hoping his ears had fooled him.

And then, in the greatest synesthesia in the history of African American literature:

“You heard her, you ain’t blind,” Walter taunted.“Ah ruther be shot with tacks than tuh hear dat ’bout mahself,” Lige Moss commiserated.

Then Joe Starks realized all the meanings and his vanity bled like a flood. Janie had robbed him of his illusion of irresistible maleness that all men cherish, which was terrible. The thing that Saul’s daughter had done to David. But Janie had done worse, she had cast down his empty armor before men and they had laughed, would keep on laughing. When he paraded his possessions hereafter, they would not consider the two together. They’d look with envy at the things and pity the man that owned them. When he sat in judgment it would be the same. Good-for-nothing’s like Dave and Lum and Jim wouldn’t change place with him. For what can excuse a man in the eyes of other men for lack of strength? Raggedy-behind squirts of sixteen and seventeen would be giving him their merciless pity out of their eyes while their mouths said something humble. There was nothing to do in life anymore. Ambition was useless. And the cruel deceit of Janie! Making all that show of humbleness and scorning him all the time! Laughing at him, and now putting the town up to do the same. Joe Starks didn’t know the words for all this, but he knew the feeling. So he struck Janie with all his might and drove her from the store.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. reinvented the field of African American studies and then went on to reinvent the role of public intellectual for our time. A historian, memoirist, literary and cultural critic, editor, screenwriter, and producer, his work spans the university, publishing, journalism, documentary filmmaking, and a hit television series, Finding Your Roots. A Library of America Trustee since 1997, he is the editor of the definitive LOA edition of Frederick Douglass’s autobiographies and co-editor of volumes devoted to slave narratives, the writings of Albert Murray, and W.E.B. Du Bois’s seminal history, Black Reconstruction.