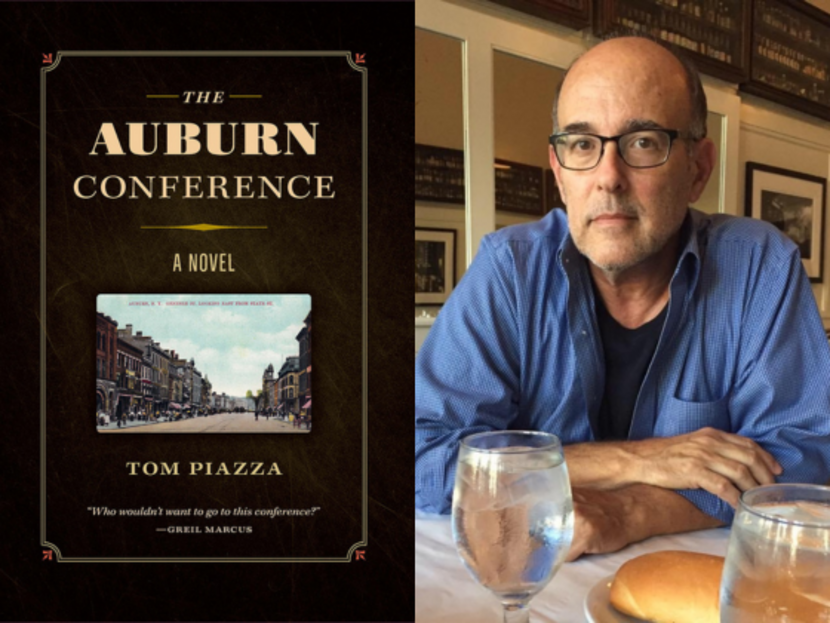

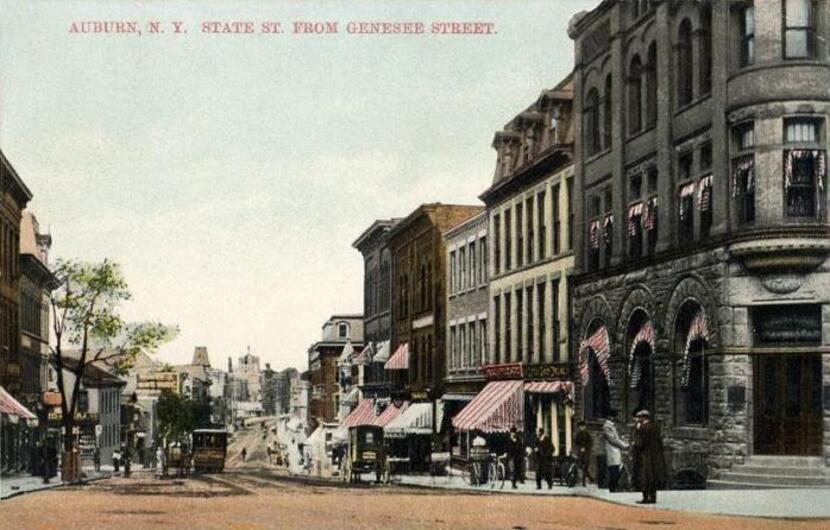

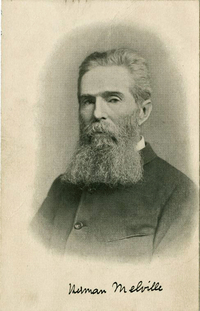

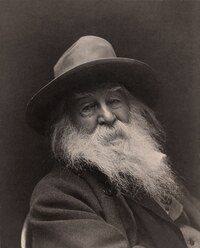

What would happen if Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, and Harriet Beecher Stowe all attended the same literary festival in upstate New York in 1883? Such is the intriguing scenario explored by author Tom Piazza in his latest novel, The Auburn Conference (Iowa, 2023), in which a who’s who of American literary eminences congregate to discuss their work and argue—sometimes vociferously—about the unsettled future of the nation some twenty years after the end of the Civil War.

“The dialogue imagined by Piazza—especially his treatment of Harriet Beecher Stowe—is dazzling,” writes historian Douglas Brinkley. “Piazza conjures a distant era that eerily translates to our own broken and troubled times. This is an epic novel by one of America’s greatest writers.”

Over email, Piazza spoke to LOA about the research underpinning his fictional gathering, how he channeled the voices of his real-life characters, and the connection between the novel’s historical setting and our own contemporary moment.

LOA: Though The Auburn Conference takes place at a fictional literary festival at a fictional college in 1883, it also maintains a fundamental plausibility, incorporating numerous historical references and weaving in abundant biographical detail. Can you describe your research process and the book’s relationship to history?

Tom Piazza: The principal characters in The Auburn Conference are all writers, so the key to them as characters, for me, was the angle between their published work and their private words. My “research” consisted mainly of reading, but I had been reading all of these writers long before I had any idea of writing The Auburn Conference. Not just the canonical works but also letters, public addresses, journals, comments about them by their friends, family, and contemporaries. I read Melville’s journals and correspondence, Emily Dickinson’s letters, Twain’s speeches and letters, Frederick Douglass’ three autobiographies and his speeches. The surprising details are often as telling as the big-picture elements, things like the fact that Frederick Douglass had a violin that he liked to play in quiet times, or that Melville wrote poems about roses late in life.

The word “history” can be used to mean, or imply, either the reservoir of available facts, or the interpretations of those facts. Obviously this novel has something to do with the collision of interpretations. I find it hard to stay interested in history of a “past” time that doesn’t resonate strongly with the present moment. The generative impulse for The Auburn Conference came out of a specific contemporary moment, just before the midterm elections of 2018, the middle of the Trump presidency, when one was reasonably wondering what the nation was doing with its freedom.

Beyond reading the writers’ own works, other research included the critic Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log and The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, both especially useful for factual background: compendia of correspondence, reviews, journal entries, etc. David Blight’s monumental biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom is indispensable. Edmund Wilson’s anthology The Shock of Recognition, a collection of (mostly) American writers, from the nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, writing about other American writers, and Patriotic Gore, his collection of essays on the literature of the Civil War, contain fascinating, valuable context. F. O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance and Constance Rourke’s American Humor are also foundational texts.

But you can do all the reading and research you want and it won’t necessarily make the characters come alive. At some point you have to shift from being yoked to a preexisting set of facts and accept that you are creating a new being, a fictional character. The research is there to serve the characters, not the other way around. The Auburn Conference isn’t a historical tract. As soon as you put recognizable personages into a work of fiction, they become imagined characters. As a fiction writer you have to claim that authority for yourself.

LOA: The novel continuously shifts perspective, putting us in the heads of numerous characters, both fictional and historical. Why did you choose this polyphonic approach?

Piazza: America is nothing if not a polyphony. The writers in The Auburn Conference produced books with strongly defined individual sounds and points of view. The idea was to make a model, or a hologram, of all these representative American voices in a simultaneous present, so that something more comprehensive might be summoned by the tension among them.

There’s polyphony, too, in the tension between public presentation and interior monologue. Any character lives not only the conscious experiences of a given moment, but the less conscious experiences; they are what they say and what they don’t say, what they want and what others want of them—the tensions among their competing impulses. Character itself is polyphonic. Saul Bellow once remarked that “the best way of writing is the Shakespearean way, a mixture of first and third person.” In other words, the private thoughts in a soliloquy create a three-dimensional effect against the dramatic situations.

In The Auburn Conference there’s a polymorphous third-person element that can act as a kind of chorus, as it does at the beginning of the book’s second part, or slide in and out of each character’s thoughts, using a sound specific to that character. Technically, the only first-person character voices that address the reader directly are those of the idealistic organizer, Frederick Olmstead Matthews, and the nameless reporter, who out of his ambition and seething envy wants to control and shape the narrative for his own purposes.

LOA: You deftly craft original speeches for many of the novel’s historical characters. How did you capture their voices and perspectives? Were any of the characters particularly difficult to channel?

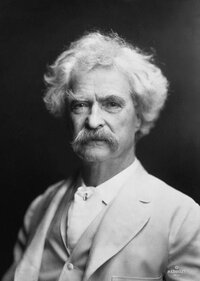

Piazza: It was a matter of listening to the characters’ voices from inside, rather than from outside, listening for what the rhythms of their speech could tell you between, or behind, the lines. Remember that, except for a very fragmentary and noisy recording attributed to Whitman, there are no sound recordings of any of these writers. They made unique voices that could reach through the page, leave a mark on you, long before the mass media homogeneity we’ve let ourselves get used to. What words they accent, where they place the emphasis, how they start a remark and where they stop, how they choose to respond to other voices in the room—it all felt natural to me. Each voice had a kind of unique frequency, which I could lock in on as the occasion arose.

By the way, that recording of Whitman, brief as it is, gave me a clue to Whitman’s speech that I might not have had otherwise. On the page, the angle between the rhetorical inflation in much of Leaves of Grass and the largely more relaxed tone of Specimen Days can tell you a lot about some of the tensions in his personality, but the sound of his spoken voice was elusive for me until I listened to the recording, in which he reads from “America.” The assertive way he speaks the words “strong. . . ample. . . fair. . .” and especially the sound of “am-ple”—a real rough scrape along that first syllable that made me hear the humble beginnings he came from, the Brooklyn in his heart.

LOA: The novel’s cast is a veritable who’s who of the era’s literary greats. How did you arrive at this particular combination of figures? And what’s behind the inclusion of two fictional characters in the conference’s lineup: the romance novelist Lucy Comstock and Confederate general Forrest Taylor?

Piazza: The principal speakers had to be able to address the larger questions that are still with us today, and I had to be happy about spending a couple of years and a couple hundred pages with them. I only included characters with strong and distinguishable voices, not just sets of ideas. All of the characters had had the experience of watching the nation finding itself, then seeing it come to the brink of dissolution, and then watching many of the possibilities for a more equitable nation begin to flower, then get dismantled. And all of them made their major statements before the Civil War, so there is an angle between their earlier perceptions and what they witnessed in the war’s aftermath. The two major voices missing are Emerson and Hawthorne, both of whom were dead by the date I chose for the conference. Emerson is a spirit that looms, to a degree, behind the event, but the nation was moving past his resolute optimism.

My feeling is that everything in The Auburn Conference could have happened last week.

I thought that a ringer or two, like Lucy Comstock and Forrest Taylor, as well as the nameless reporter, could cast a usefully cold eye on some of the onstage discourse. In the novel, Frederick Douglass meets an antagonist, the Confederate memoirist Taylor, an apologist for slavery, who represents the reaction against Reconstruction, the building of that counter-myth of the South’s “Lost Cause.” His character is based in large part on Zachary Taylor’s son Richard, himself a high-ranking Confederate officer, who published an 1879 memoir entitled Destruction and Reconstruction, which could serve as an urtext of Southern grievance. Forrest Taylor’s character owes much to the sound and posture evident in that book.

Lucy Comstock is a force of nature, utterly commercial and also very practical—immune, ironically enough for a romance novelist, to any “romantic” view of American prospects. They are irrelevant to her except as they help her to sell books. She could be seen as a feminist in her independent spirit and willingness to stand up to the male figures on the panel, but clearly the content of her books is objectionable to some of the suffragists in attendance. Harriet Beecher Stowe finds her irritating almost beyond endurance.

LOA: Though the particulars may be different, it’s hard not to hear echoes of our current national debates over race, gender, and the role of government in the book’s post–Civil War setting. To what extent were you thinking of through lines to the present when crafting the novel? Are there some less obvious parallels between then and now you uncovered?

Piazza: Those “through lines” are in some ways the point of the book. My feeling is that everything in The Auburn Conference could have happened last week. The obvious echoes or parallels are lying around in plain sight. The implications of some of the more apparently literary debates might offer a few less obvious ones. I think there’s a parallel around the implications in the argument between Whitman and Melville—Whitman’s grand embrace of the nation’s supposedly manifest destiny, his celebration of the Homeric catalogues of diverse multitudes, versus Melville’s sense of doom at the implications of that boundless entitlement, the brutality that makes it possible and the monomaniacal, antidemocratic will to domination that could spell the ruin of it all. And maybe the other parallel might be the perennial, unerasable vein of the irrational in a nation carrying a huge measure of unacknowledged, and perhaps unacknowledgable, guilt over the slaughter, subjugation, and barbarity that made all that possibility possible.

LOA: Literary conferences are ubiquitous today, though it’s rare to see a lineup of comparable variety and star power as that depicted in the novel. Assuming no constraints of funding or availability, which living writers or thinkers would you invite to speak at the Auburn Conference of 2023?

Piazza: The framing of the conference would need to have a different focus—not on the “future” of America per se, but on the recognition that we keep reviving the same issues, choking on the exhaust of the same mistakes. What does that mean, and is there any way to break that cycle? I would have liked to invite members of the generation and a half of voices whose last owners have just finished dying off: Ralph Ellison, Norman Mailer, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Allen Ginsberg, Gore Vidal, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, maybe Ken Kesey, maybe Christopher Hitchens, maybe Kurt Vonnegut—writers with powerful, distinct voices who still took the idea of the American project seriously, the idea of a collective project that could make it possible for citizens to realize their individual potentialities. You could see that as an oxymoron, or as a paradox—either a terminal cul-de-sac of contradiction, or a set of tensions that open out and generate energy.

Anyway, I think there’s a lot of resistance currently, across the entire ideological spectrum, toward the idea of the individual in the first place—a tropism toward submersion in a mass, or a team, complete with labels. That in itself might have to be the conference’s theme. Who would be invited to speak today? I’ll have to demur on that; I wouldn’t want to take the risk of leaving anyone out.

Tom Piazza is a novelist and a writer on American music. His twelve books include the novels The Auburn Conference and City of Refuge, the post-Katrina manifesto Why New Orleans Matters, and the essay collection Devil Sent the Rain. He was a principal writer for the HBO drama series Treme, and the winner of a Grammy Award for his album notes to Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues: A Musical Journey. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Bookforum, the Oxford American, Columbia Journalism Review, and many other periodicals. He lives in New Orleans.