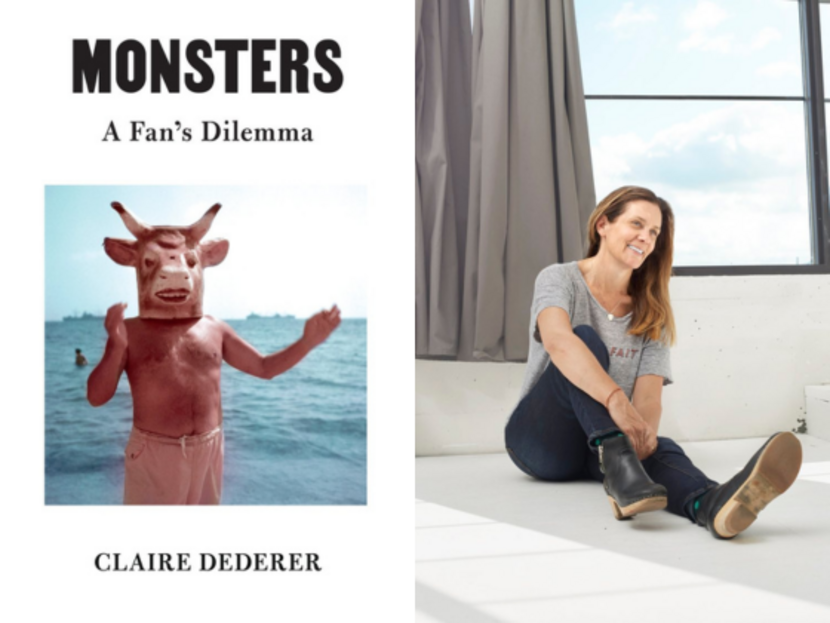

When Claire Dederer published her viral essay “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” in The Paris Review in 2017, it opened up a vital conversation about how to take the moral and creative measure of writers, painters, musicians, and filmmakers who, in her words, “did or said something awful, and made something great.” On April 25, she’ll publish Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma (Knopf), expanding on that influential piece to probe pressing questions about genius and transgression, gender and deplorability. Can we appreciate the works of Hemingway, Mailer, and Pound despite their authors’ unforgiveable behavior—and under what terms, with what caveats and compromises in place?

“Slyly funny, emotionally honest, and full of raw passion, Claire Dederer’s important book about what to do when artists you love do things you hate breaks new ground, making a complex cultural conversation feel brand new,” writes Ada Calhoun. “Monsters elegantly takes on far more than ‘cancel culture’—it offers new insights into love, ambition, and what it means to be an artist, a citizen, and a human being.”

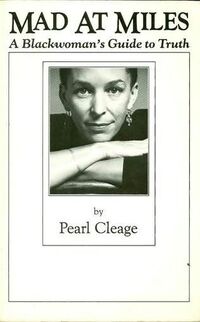

Below, Dederer discusses her search for precedents for her project and finding inspiration in author and critic Pearl Cleage’s 1990 book about her relationship with the work of Miles Davis, Mad at Miles: A Blackwoman’s Guide to Truth.

When I started to explore the whole “what do we do with the art of monstrous men” question, I immediately found myself frustrated. I wanted an answer, and the main quality I was looking for in that answer was that it would have already been arrived at by someone else—preferably someone a lot smarter than myself. I didn’t plan to write a book about the question; I didn’t want to be the person charged with exploring it. Instead, I desperately searched for a writer or thinker who would tell me what to do or what to think. That person was, alas, nowhere to be found.

The twentieth-century New Critics like Cleanth Brooks seemed to sever the artist from his (oh, his) work with fearsome neatness, as if artist and art were two distinct entities that could be split as fatally and finally as the atom. This was not what I was looking for; I sensed the essential untruth of the solution: the intention to separate the art from the artist was not the same as actually being able to do so.

I cast about for years, simultaneously writing the book that would become Monsters and looking for this person who would help me think about the problem. And then I stumbled onto the work of Pearl Cleage. A novelist, critic, and playwright, Cleage published Mad at Miles: A Blackwoman’s Guide to Truth in 1990. The title essay explored her relationship with the work of a beloved and monstrous artist: Miles Davis. Davis was an acknowledged genius and an acknowledged abuser, and Cleage loved him.

After years of writing about the sins of the artists and the anguish of the audience, Cleage brought me around to the very heart of the matter, the hot core: love.

Davis wasn’t just background music for Cleage. His music shaped her days—in some ways seemed to shape her very identity. She writes about how Davis saw her through the phases of her life: “The Bohemian Woman Phase. The single again after a decade of married phase. . . . The cool me out quick cause I’m hanging by a thread phase. For this frantic phase, Miles was perfect.”

The essay was a revelation to me—especially the way Cleage was consumed with the problem, at war with it. In the essay, she loves Davis and she rails at him. Her writing possessed what I had been missing: not just a deep intellectual and emotional comprehension of what was at stake when we consume the work of the monster artist, but a kind of brilliant, fierce urgency. Just as Cleage was besotted with Davis, I became besotted with Cleage. After years of writing about the sins of the artists and the anguish of the audience, Cleage brought me around to the very heart of the matter, the hot core: love.

Cleage’s writing had an enormous generosity—she told the story of her own personal love of Davis, and her own personal betrayal. And that opened a door for me; once I’d read Mad at Miles, I was able to trust myself more.

What we do with the art of the monster artist, in the end, is a very personal question. Consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist that might disrupt the consuming of the art; the biography of the audience member that might shape the viewing of the art. This seems like a simple thought, but was very hard-won and took years to grasp; longer still to find the language to describe it. I had to fall in love with the work of Pearl Cleage to learn its truth.

Claire Dederer is the author of Love and Trouble, and the New York Times best-selling memoir Poser: My Life in Twenty-Three Yoga Poses, which has been translated into twelve languages. A book critic, essayist, and reporter, Dederer is a longtime contributor to The New York Times and has also written for The Atlantic, Vogue, Slate, The Nation, and New York magazine.