The 1970s marked a turning point in science fiction written by women: the decade’s resurgence of feminist politics and receptiveness to literary experimentation inspired paradigm-shifting works that still retain their revolutionary power. From the separatist female utopias envisioned by Joanna Russ, to the critiques of patriarchal technocentrism found in Lisa Tuttle and C. J. Cherryh, to the diversity of women’s experiences explored by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro and Ursula K. Le Guin, the era’s adventurous and daring visions dismantled forever the false notion that sci-fi was conceived by and for men.

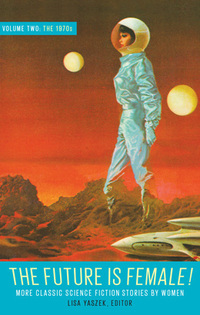

In the recently published The Future Is Female! Volume 2: The 1970s, the companion volume to The Future Is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women, editor Lisa Yaszek punches in the coordinates for an interplanetary, multidimensional tour through this out-of-this-world oeuvre.

Via email, she answered questions about the decade’s outpouring of feminist SF and its myriad intersections with our present moment.

LOA: Why focus on the 1970s for this volume? What currents in culture, politics, and history fed into that era’s science fiction written by women?

Lisa Yaszek: I wanted to focus on women’s science fiction from the 1970s because that is the moment when feminist science fiction is born! Women have always written speculative fiction: Margaret Cavendish’s 1666 protonovel The Blazing World casts its author as a human adventurer turned dimension-traveling philosopher/warrior queen who saves her homeland with an alien army of biomechanical animals. Mary Shelley’s wildly popular 1818 Frankenstein gave us both the first modern image of the mad scientist and the first feminist critique of scientific inquiry unhinged from morality and ethics. Pauline Hopkins’s 1902–3 serialized novel Of One Blood imagines an ancient African civilization powered by advanced blue and green technologies and guarded by a female military elite (yes, a century before the Black Panther films).

Indeed, we specifically chose many of the stories in FIF2 because they are both artistically innovative and politically passionate.

Furthermore, as I explain in the introduction to The Future is Female: Volume 1 (FIF1), women may have been a distinct minority in the early and midcentury American magazine community where science fiction coalesced as a popular genre, but they certainly made their voices heard. Speculative pioneers including Leslie F. Stone, Judith Merril, and Rosel George Brown wrote all the same kinds of stories as their male counterparts while expanding the fledgling genre’s roster of female characters to include alien queens, lady scientists, and (un)happy housewife heroines—and showing readers that laundries and living rooms could be just as exciting sites of techno-scientific action as laboratories and launchpads. And yet, despite these similarities, the first generations of women writing SF never really saw themselves as a coherent political or aesthetic group.

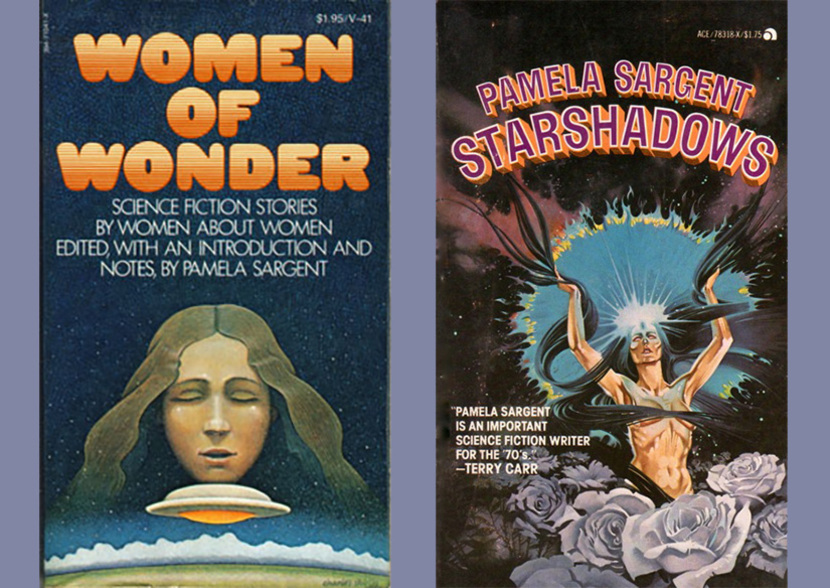

That’s what’s so exciting about the 1970s: that decade was truly a watershed moment for women in SF. Women had always comprised about 15 percent of the SF creative community, and author-agent Virginia Kidd has noted that those numbers did not really change in this era. What did change is that suddenly women were much more visible because they were winning major awards, taking over key professional organizations, and creating exciting new anthologies, fanzines, and artwork. Perhaps more importantly, they were also beginning to think about themselves in collective terms, recovering older traditions of speculative writing by women while creating new ones of their own.

LOA: To what extent were the authors in this volume aligned with or inspired by feminist politics? Did they consider their work political or activist?

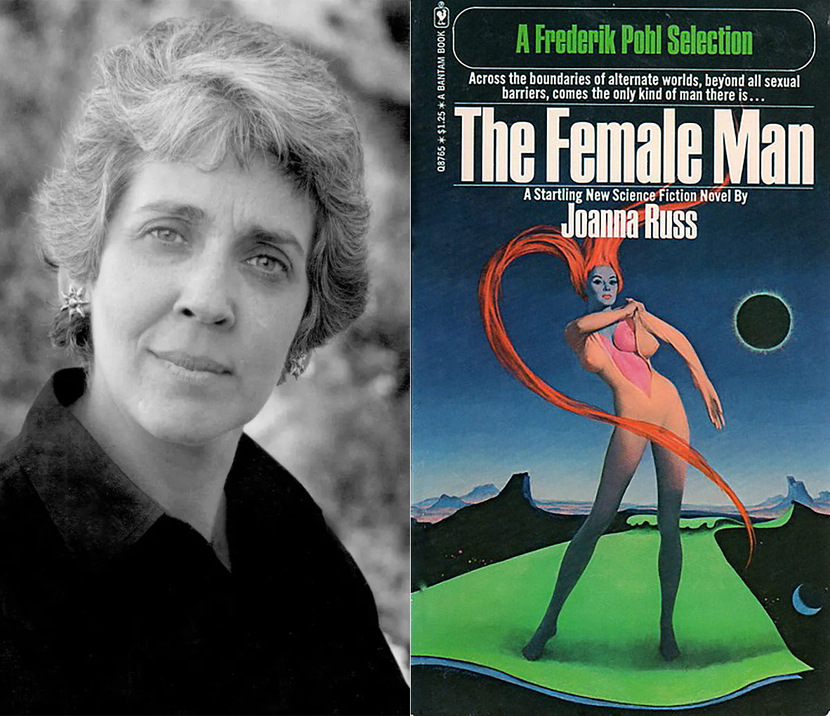

Yaszek: Many of authors in this volume were directly inspired by feminism. The most famous example is probably Joanna Russ, who took seminars with Betty Friedan (author of The Feminine Mystique and founding member of The National Organization for Women) and Kate Millett (one of the first feminist literary critics). Lisa Tuttle and Joan Vinge have both spoken passionately about how they and many other young women of their generation were drawn to SF because it celebrated change and presented options not yet available to women in our world, and Vonda McIntyre remembers being directly inspired by pioneering feminist SF writers including Russ, Andre Norton, Kate Wilhelm, Anne McCaffrey.

Other women who incorporated feminist themes in their fiction were also real-life activists: Miriam Allen deFord was a suffragist and birth control advocate in her teens; Eleanor Arnason (whose aunt was the eighth president of NOW) has been politically involved in coal miner strikes, writers unions, and Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party politics in Minnesota; and Gayle N. Netzer, who attended the 1977 National Women’s Conference, contributed feminist commentary to her local newspaper.

[W]omen challenged science fiction’s historically limited representations of women as nubile alien monsters and hapless love interests with stories of women actively building new futures at every stage of life.

Indeed, we specifically chose many of the stories in FIF2 because they are both artistically innovative and politically passionate. I think readers will see that by harnessing the political energies of the era, women writing SF in the 1970s expanded the genre in three ways. First, authors paid homage to the feminist utopias of their suffragist predecessors with tales of all-female societies where women can develop as fully realized people, as in Russ’s “When It Changed,” Sonya Dorman Hesse’s “Bitchin’ It,” and Netzer’s “Hey, Lillith!” They also warned about the dystopian futures that might result from the destruction of such communities, as in Tuttle’s “Wives” and Wilhelm’s “The Funeral.”

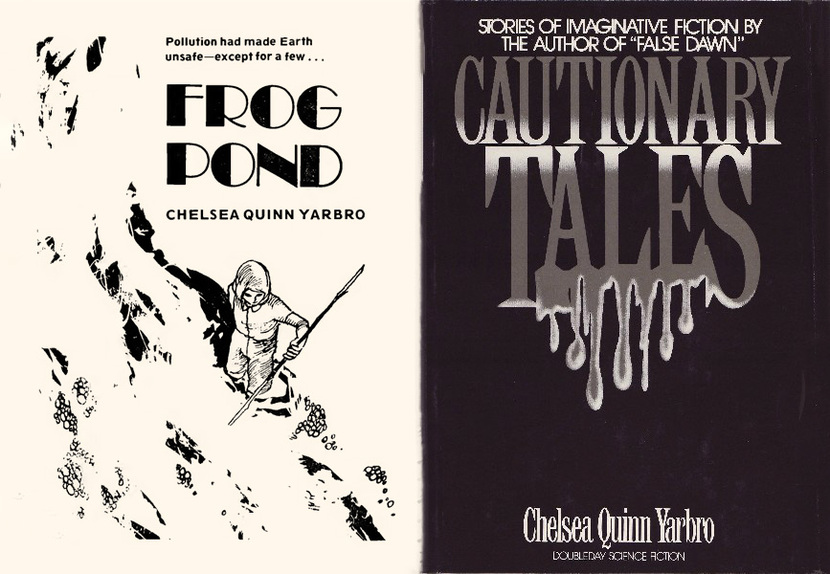

Second, women challenged science fiction’s historically limited representations of women as nubile alien monsters and hapless love interests with stories of women actively building new futures at every stage of life, whether they are mutant girls thriving in postapocalyptic landscapes (Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s “Frog Pond”), planetary presidents indulging their sexual kinks (deFord’s “A Way Out”), or elderly women leading revolutions (Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Day Before the Revolution”).

Third, women revised the core themes of their chosen genre to generate new perspectives on science, gender, and society. This is particularly evident in metafictional tales such as Arnason’s “The Warlord of Saturn’s Moons.” But it is also evident in tales that critique the belief that science will always generate better futures—see especially Alice Sheldon’s “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (published under the pseudonym James Tiptree, Jr.) and “The Screwfly Solution” (published under Raccoona Sheldon)—and that map the raced and gendered assumptions of American empire (as in Kathleen Sidney’s “The Anthropologist”).

Of course, it’s important to recognize that not all the authors included in FIF2 agreed about what constituted feminist activity or writing. Connie Willis (represented here by “Daisy, in the Sun”) recalls being chastised by other women writers for continuing to write housewife heroines in an era when women were calling for educational and professional equity with men. Le Guin described herself as coming to feminism slow and late and only after much debate with her sister authors and much reading of feminist theory and literature.

But that is part of what makes the stories in this collection so exciting! The women who wrote them were not just having aesthetic and political arguments with their male counterparts, they were arguing with each other as well—a good reminder to us all that feminism is not just some predetermined set of critiques and goals, but a living, evolving body of knowledge and practice that is as diverse and complex as the people who ascribe to it.

LOA: How diverse were women SF writers of the era? Were there many women of color, or queer or trans women, working in the genre at the time?

Yaszek: Women in 1970s science fiction were about as diverse as most American feminists—and most male science fiction writers—of that time. That is to say, they were largely white, middle-class, cisgender, and college-educated. Having said that, we need to remember that while they may not seem particularly radical to us today, the fact that any women were standing up together to represent in this period was remarkable.

Furthermore, all of those largely white, middle-class, cisgender, and college-educated writers did indeed do something remarkable to increase the diversity of SF: they told stories about women from every stage of life. For example, Wilhelm’s “The Funeral” and Willis’s “Daisy, in the Sun” revolve around the potentially universe-changing event of a teen’s first period. And in what I think is the most exciting development of the era, stories including Kathleen Sky’s “Lament of the Keeku Bird,” Le Guin’s “The Day Before the Revolution,” and M. Lucie Chin’s “The Best is Yet to Be” insist that the future really belongs to middle-aged, menopausal, and old women.

The nascent feminist science fiction community was also home to pioneering LGBTQ+ artists Joanna Russ, Vonda McIntyre, and C.J. Cherryh, and a number of authors, both queer and straight, challenged the heterosexual binary in their fiction. The Russ vignette included in this volume, “When It Changed,” specifically revolves around a future lesbian utopia threatened by male invaders looking for reproductive partners, while the hermaphroditic aliens of Sky’s “The Anthropologist” and Tuttle’s “Wives” are forced into grotesque parodies of conventional human gender roles by well-meaning scientists and rapacious soldiers alike. And while we were not able to include essays in this volume, it’s worth noting that fan-turned-author and editor Jessica Amanda Salmonson chronicled her transition in the SF fanzines of this era as well.

We also see the first glimmers of racial diversity in the SF community of the 1970s. Of course, people of color have always told speculative stories: Indigenous American cosmologies across the North American continent include tales of other dimensions and worlds, and Black Americans have written SF since Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 poem “On Imagination” depicted enslaved Black artists becoming emancipated star children by riding the mothership of imagination to the stars.

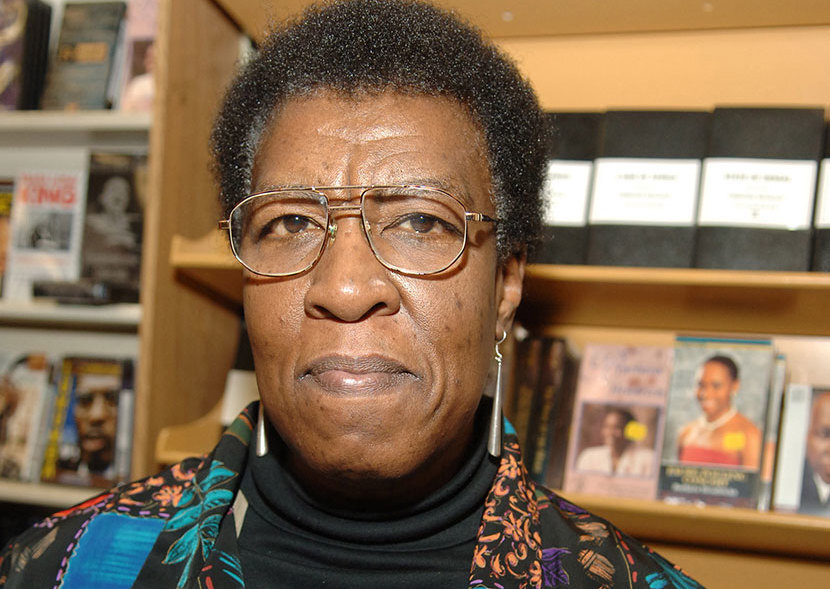

For the most part, however, authors of color published within their own literary communities until the 1960s and ’70s. Samuel R. Delany is often rightly cited as the first known African American to publish in the SF pulps, and Black women were right there with him. Luise White was the only Black woman to participate in the infamous Khatru symposium, “Women in Science Fiction,” along with Russ, Le Guin, Tiptree, Yarbro, and Wilhelm. And Octavia E. Butler attended the prestigious Clarion Writers Workshop in the early 1970s and wrote her Patternmaster series and the time-travel slave narrative Kindred during this era.

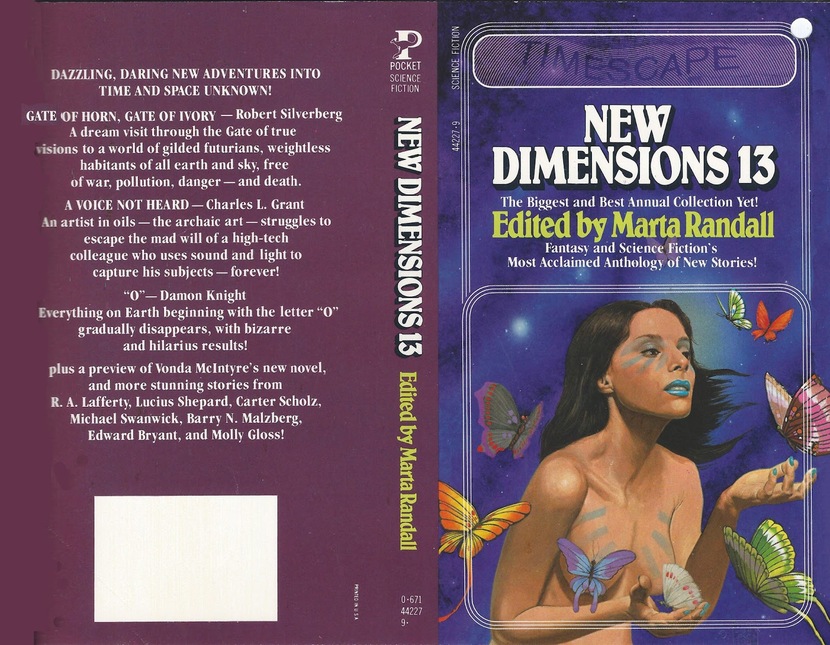

Joan Vinge and Marta Randall shared information about their respective Indigenous American and Lebanese-Mexican heritages in biographical sketches from this period but were less likely than Butler to make race a central concern in their stories. Having said that, the stories included in FIF2 from both authors do anticipate the kind of intersectional thinking that is increasingly common in SF today: the heroine of Randall’s “A Scarab in the City of Time” is an anthropologist whose work studying a domed society of white supremacists is made that much more dangerous by the fact that she is a woman of color, while Vinge’s “View from a Height” follows an isolated astronaut whose adventures invite us to rethink our assumptions about gender and (dis)ability.

LOA: What specific stories or writers in the volume would you call out to readers? Any personal favorites?

Yaszek: One of my favorite parts of editing the volumes was meeting authors who were well known in their time but who, for whatever reasons, have not always been well represented in SF history. I was personally blown away by Elinor Busby’s “A Time to Kill.” Busby was the first woman to win a Hugo award, in this case for co-editing a fanzine with her husband, F.M. Busby. Indeed, Elinor Busby is often remembered only in terms of her fanzine work and in relation to her husband, which is a shame. “A Time to Kill” is a short time-travel tale with an ending that should be completely obvious but is not—a testament to Busby’s skill with plot development.

Trying to pick my personal favorite stories is like trying to pick a favorite child—you probably can do it, but should you tell anyone? Having said that, I’ll pick two stories I always recommend to people, one of which I’ve been reading since I was a kid and one of which I encountered for the first time while editing this volume.

My old favorite is Joanna Russ’s “When It Changed,” for sure. My parents were huge fans of the New Wave and I remember reading Russ around the same time as I came to consciousness as a human in my early teens. I didn’t always fully get what she was writing about, but I got enough that I kept coming back for more: her anger was my own, and her humor was a skill to which I aspired. “When It Changed” was written on the eve of Roe v. Wade and I suspect at the time was meant to serve as a reminder that progress is not necessary teleological, and that even when women are literally winning the future, we need to be vigilant against the forces that would undermine us so they can continue, in Russ’s own words, to “hog all the good things” in life.

This is another story I teach frequently, and I can tell you that it has taken on new resonance for young people of all sexes and genders this past year with the overturn of Roe. And of course, I teach this story not just because of how its message connects with both past and current events, but because it’s so beautifully written. The reversal of the classic alien invasion narrative, the slow reveal of what Earth men really want, the drama of our narrator struggling to wrap her mind around a future that has suddenly shifted radically and without her consent—it’s a slow burn that lingers in the mind, and an utterly perfect example of both New Wave and feminist SF.

Our ideas about what constitutes acceptable violence in art and culture really are changing for the better, however slowly and however much some people fight them.

The other story I encountered for the first time that knocked my socks off was Connie Willis’s “Daisy, in the Sun.” I don’t think I’d ever read an SF story about a girl’s first period before and suddenly I realized that was a real shame—SF is all about extrapolating from our experiences with the material world to create moving art, and this story does that in spades. I recently did some consulting for a scholar who is writing a history of menstruation in Western medicine and culture and who wanted to know how SF authors have approached this topic (short answer: they didn’t until women start writing about menarche and menopause in the 1970s). I gave her a batch of stories including “Daisy” and she was also blown away by the power and sheer beauty of Willis’s tale. And it’s not just scholars who react that way. I had the pleasure of hiring a small team of student researchers to help produce FIF2 and they told me they would quit en masse if I didn’t include “Daisy” in the volume. So, students, this one’s for you!

LOA: How do the visions in these stories read to us today—any especially prescient or provocative ideas, or things that may seem dated or anachronistic?

Yaszek: I truly believe that the authors we’ve featured in FIF2 are so talented that the emotional cores of their stories still resonate half a century later. Having said that, elements of certain stories are pegged to cultural attitudes and aesthetics that no longer resonate quite the same way with younger readers. The team of student researchers for FIF2 was particularly forthright in that respect, and we ended up dropping one story from the anthology based on their feedback: Lisa Tuttle’s “Stone Circle,” a chilling proto-cyberpunk tale about sexual exploitation of women under capitalism. My commissioning editor and I both thought it was a beautifully written story that made gut-wrenching points about how economic pressures drive people of all sexes and genders to participate in the sexual exploitation of women, and we agreed that the key moments of violence were very much in line with the aesthetics of the era.

My research team members, however, absolutely could not wrap their heads around the story. From their perspective, the violence was gratuitous, and they insisted that there were many other excellent stories—including Tuttle’s “Wives,” which ended up replacing “Stone Circle”—that made the same points about gendered violence without potentially fetishizing those same acts. I was blown away by that conversation; it simply never occurred to me that the story was too violent. And then I got really excited, because the way my students reacted means that feminists and other progressive people interested in better futures for all are making an impact. Our ideas about what constitutes acceptable violence in art and culture really are changing for the better, however slowly and however much some people fight them.

The student team also felt some emotional distance from three of the major techno-scientific themes informing SF of the 1970s: the concern about overpopulation that drives Doris Piserchia’s “With Pale Hands”; the sense of urgency about nuclear war at the center of Yarbro’s “Frog Pond” and Cherryh’s “Cassandra”; and the depiction of mental health issues in “Cassandra.” This is not to say that they disliked the stories—they actually thought the Piserchia story had a new urgency in an era where we use online technologies to both connect and disconnect from sex, and everyone wanted to be the heroine of “Frog Pond”! Initially, the women on my team had mixed feelings about “Cassandra” and what felt to them like a very dated depiction of women’s mental health treatment that sat uneasily with Cherryh’s points about nuclear war (a concern that they recognize is still with us today, but that for various reasons does not seem to be as much at the center of our collective consciousness). Eventually, however, they were won over by the authenticity of the protagonist’s emotional journey and Cherryh’s marvelously surreal writing.

For the most part, however, I think that LOA readers, like my research team, will find the stories in FIF2 to be remarkably prescient and timely. Readers interested in issues of reproductive justice might be particularly interested in Russ’s “When It Changed” and Wilhelm’s “The Funeral”—the latter of which directly anticipates the world of The Handmaid’s Tale—for their meditations on the patriarchal control of women as reproductive bodies. Readers who enjoy a good metafictional tale or who are interested in gender relations will particularly enjoy Arnason’s “Warlord” and Netzer’s “Hey, Lillith!” for their inventive depictions of women who walk away from the smoking ruins of patriarchy to create new art beyond the end of the world.

And I think readers will enjoy the many stories here that show us how women might build hopeful futures around things they want but lack in the here and now (of both the 1970s and today). And that’s exactly why we want—and need—to read old feminist SF in the present. It shows us we are not alone in our hopes and fears about (patriarchal) techno-scientific modernity; other people have grappled with challenges and opportunities similar to those we face, and they have left these amazing records of it for us, transformed powerfully into art that connects us to the past and provides templates for action in our own time to build new and better futures for all.

Lisa Yaszek is Regents Professor of Science Fiction Studies in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech and past president of the Science Fiction Research Association. She is the author of Galactic Suburbia: Recovering Women’s Science Fiction and co-editor of Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction.