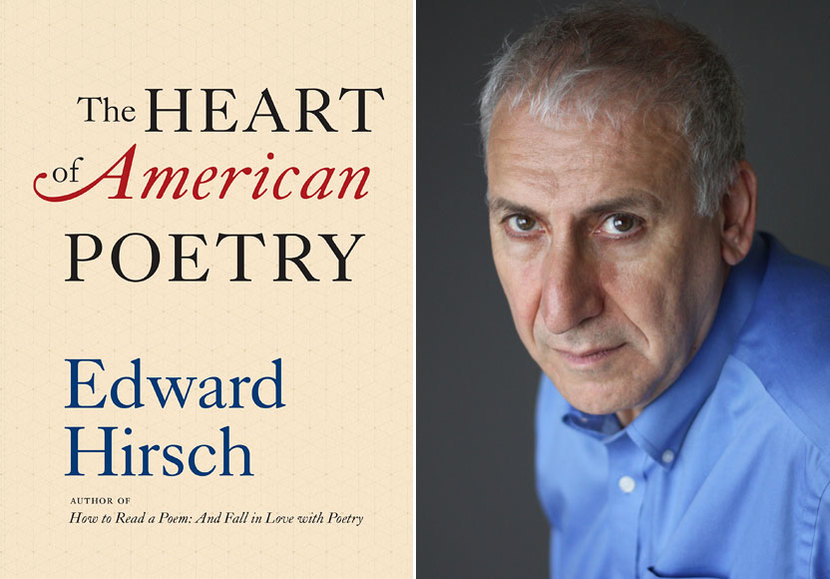

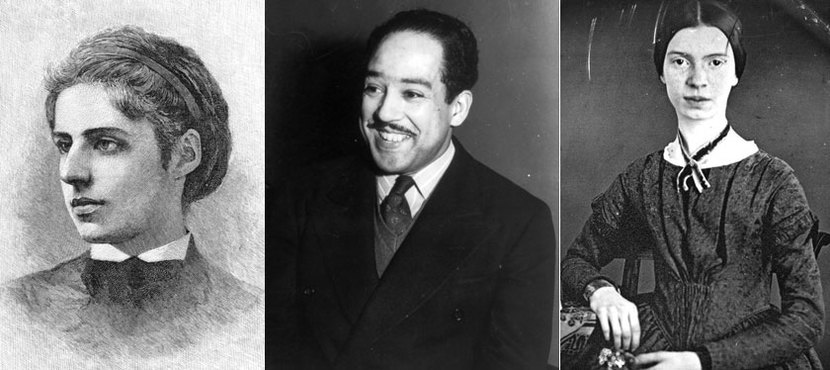

Arriving for National Poetry Month, The Heart of American Poetry by Edward Hirsch offers a major new reading of the American tradition by a poet who is also a celebrated champion for the form. Far more than an anthology, the book presents a sequence of deeply personal readings of forty essential American poems, ranging from Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley in the colonial period all the way to Joy Harjo in the twenty-first century.

Honoring what he calls “the elasticity of American poems, the complex of our registers,” Hirsch sets out to explore how these works have shaped his own life and how they might move and uplift fellow readers at an especially fraught moment in the nation’s collective life.

Hirsch is the author of ten books of poems and six books of prose and the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships. He serves as president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and lives in Brooklyn. Via email, he answered our questions about The Heart of American Poetry.

Library of America: Near the end of your introduction you write, “American poetry is one of the underutilized resources of American culture.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

Edward Hirsch: What I mean is that American poetry is one of our great underrecognized arts. Poetry has been taught so poorly in schools that most people don’t realize how seriously American poets have been thinking about issues of tremendous importance to the culture at large. From the beginning, our poets have been thinking about American life, individually and collectively. I’d like our poetry to be at the heart of the conversation about American life, who we are and what we represent.

LOA: The poems that you focus on are a mix of the canonical and the perhaps less well known. Among the former, which poem or poems surprised you the most on rereading here? Do great poems evolve or otherwise change as we revisit them later in life?

Hirsch: Great poems are endlessly surprising. You see different things in them at different times of your life. There were many trap doors that opened as I was writing about poems that I thought I knew well. I will mention two of my greatest revelations.

The first is Ezra Pound’s translation of “The River Merchant’s Wife: a Letter.” The poem is an adaptation of a ballad by a Chinese poet that he calls by his Japanese name “Rihaku.” This is the Tang Dynasty poet that I first knew as Li Po, and we can recognize as Li Bai. I have come to recognize that the poem is more mediated than I ever realized. It is part of an elaborate process of cultural transmission. It’s not a solely authored text. I came to understand that we don’t really have a name for its intercultural dependencies, its complex of collaborators, many of them unknown to each other, the work of oral and written poets from different centuries and cultures. I track them in my essay.

The other is Langston Hughes’s poem “Harlem.” I have taught this poem many times over the years. I have known Hughes as a jazz poet, but never tried to pinpoint out how jazz might be operating as a structural principle in his work. We tend to think of “Harlem” as a stand-alone anthology piece. It is important by itself, but it is also deeply embedded in his book Montage of a Dream Deferred. Hughes realized that he had hit upon something anthemic in the phrase a dream deferred. I trace how he dilates on it throughout the book. My essay shows how Hughes kept wringing out the changes, and thus turned bebop into his own written music.

LOA: As you also describe in your introduction, you began writing this book during the pandemic shutdown of 2020. How did that experience shape your thinking about American poetry?

Hirsch: I realized as I was writing that I was responding to three viruses. The first was the virus that virtually shut down the entire world—an unprecedented strangeness. Another virus also rematerialized—the virus of racism, individual and institutional, a sickness unleased. The third virus is a sustained authoritarian threat to democracy that continues to bedevil American life.

The constellation of these three intertwined viruses, three powerful threats to the republic, led me to reappraise the place of poetry in our culture, the work that it does, and how poetry contributes to the American experience, what it means to American experience and life.

LOA: One of the pleasures of this collection is how much American history it contains, from the Puritan era represented by Anne Bradstreet to the reckonings for justice we’ve witnessed in the past decade. Did you expressly intend to write a kind of history?

Hirsch: I didn’t set out to write a history of America, but I did try to pinpoint each poem in its cultural and historical context. These forty poems weren’t written in a vacuum. I discovered that by situating them in time I also came to have a deeper sense of American history, how poetry operates within that history, how poems reflect and defy their moment in time. It was exciting to see the American pageant unfolding.

LOA: You are attentive to the technical procedures of each of these poems, i.e., what each one does. Why is it important to include these kinds of explanations in your readings?

Hirsch: A poem is a work of art, a made thing. It is not just a delivery system for a message. I try to understand how each poem works as a created object. This means being alert to formal matters. I believe these technical concerns help us to understand how a poem achieves its effect, how it becomes a lived and meaningful experience.

LOA: You call this an “intensely personal book about American poetry.” In what ways is it personal for you?

Hirsch: This book has many autobiographical moments and revelations. I am not writing a disinterested series of forty essays. I am writing about poems that are deeply meaningful to me personally. I try to explain why in each piece. I had never written a book about American poetry per se, and I realized that this was my singular chance. I wanted to write about individual poems of significance, but I also wanted to define for myself the American project in poetry. What have I been participating in all these years of my life? I wanted to see if I could get to the heart of the matter.