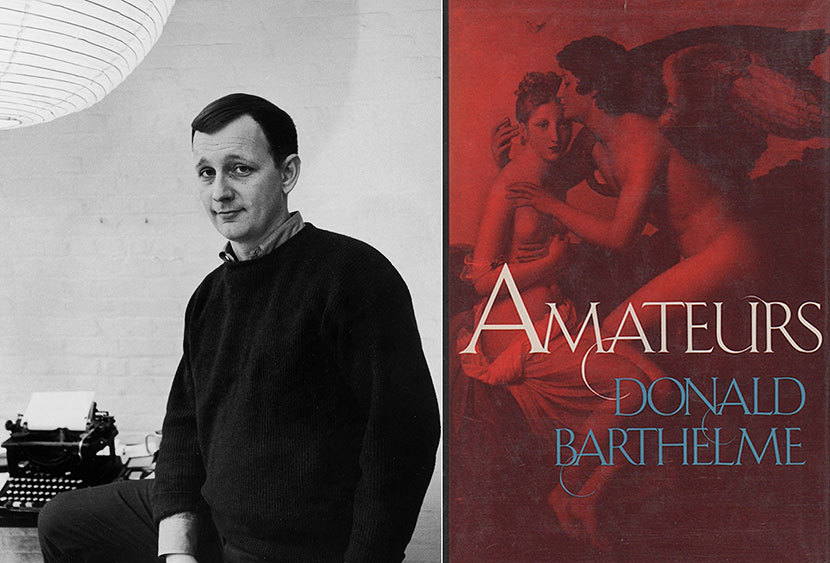

Donald Barthelme (1931–1989)

From Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories

Donald Barthelme was born 91 years ago, on April 7, 1931.

During a three-decade career cut short by his death at the age of 58, he published four novels, seven story collections, a popular children’s book, and two retrospective anthologies of his short fiction. Almost immediately after his arrival in Manhattan from Texas in the early 1960s, he became a regular contributor to The New Yorker and went on to publish 129 stories in the magazine, as well as dozens of “Notes and Comment” pieces. He even filled in briefly for Pauline Kael, writing movie reviews during her sabbatical.

Splitting his time between New York and Texas, he also became a beloved teacher at the University of Houston, where he cofounded the school’s creative writing program. Tracy Daugherty, a former student, opens the biography Hiding Man with a memory salvaged from one of Barthelme’s classes: “The assignment was simple: Find a copy of John Ashbery’s Three Poems, read it, buy a bottle of wine, go home, sit in front of the typewriter, drink the wine, don’t sleep, and produce, by dawn, twelve pages of Ashbery imitation.” Barthelme’s goal, Daugherty realized much later, was to disrupt the inclination in student writing to be “so overdetermined” and to foster the “irruption of accident.”

One of Barthelme’s most popular and most-anthologized stories is “The School,” which was included in his 1976 collection Amateurs. Like all his stories, “The School” is short—just over 1,200 words. Writers as varied as George Saunders, Joyce Carol Oates, T. Coraghessan Boyle, and Lorrie Moore have singled it out for inclusion in anthologies and have used it in their classrooms, and it is often the first exposure for students to what has become known as “postmodernism.” Saunders wrote a well-known essay called “The Perfect Gerbil” explaining why the story succeeds and why readers react to it and interpret it so differently. To begin to understand Saunders’s seemingly bizarre title, you’d really have to read the story—which you can do, for free, at our Story of the Week website.