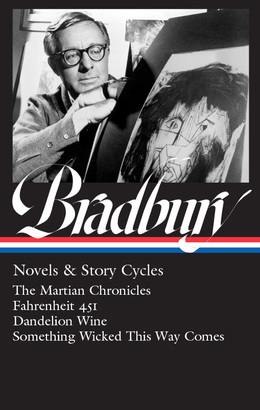

Library of America welcomes a visionary storyteller into its roster with the arrival of Ray Bradbury: Novels & Story Cycles, which collects four of its author’s most beloved books: The Martian Chronicles (1950), Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Dandelion Wine (1957), and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962).

With these four works Bradbury helped elevate speculative fiction from the newsstand pulp magazines to the vital center of American literary culture, and their influence only continues to grow in the twenty-first century. Neil Gaiman may have put it best when he stated, “I can imagine all kinds of worlds and places, but I cannot imagine a world without Bradbury.”

Novels & Story Cycles is edited by Jonathan R. Eller, who brings impeccable credentials to the task. He is the author of the definitive, three-volume Ray Bradbury biography and served as general editor of the Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury and The New Bradbury Review. Eller is also emeritus Chancellor’s Professor of English at Indiana University and co-founder of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies, which he directed for a decade until his retirement in 2021. Via email, Eller discussed distinctive features of LOA’s Bradbury edition, and how Bradbury’s characteristic themes are thrown into greater relief by having these particular titles brought together in one volume.

Library of America: The new LOA Bradbury volume includes what became his settled intention for the text of The Martian Chronicles. Can you explain why this is noteworthy, and how this version of the book differs from other editions that have been circulating for decades?

Jonathan R. Eller: Bradbury’s full crafting of The Martian Chronicles resulted in the addition of two stories that did not appear in the 1950 Doubleday first edition. Just prior to the setting of Doubleday’s proofs, he removed “The Fire Balloons,” a story of priests who must reconcile their faith with the existence of intelligent life on Mars, but Bradbury soon came to regret this decision. In some later editions he restored “The Fire Balloons” and added “The Wilderness,” which together with the first edition contents came to represent his settled intention for this bridged cycle of Martian stories. As the Chronicles became an enduring science fiction classic, the publishing history on both sides of the Atlantic complicated the stability of the book for decades to come.

He quickly restored “The Fire Balloons” for the British first edition of the Chronicles (published as The Silver Locusts, 1951), but that presented a new problem for his British publisher, Rupert Hart-Davis: in America, “The Fire Balloons” had already been shifted to The Illustrated Man, Bradbury’s next Doubleday collection of science fiction tales. Hart-Davis managed the situation by moving “Usher II” from The Silver Locusts to the British edition of The Illustrated Man to replace “The Fire Balloons.” For the 1953 British Science Fiction Book Club edition (published under the restored title of The Martian Chronicles), Bradbury added “The Wilderness,” a newer story that offered a pioneer-style account of the independent women who come to Mars for a new life among the first settlers. This edition included “The Fire Balloons,” but not “Usher II.” Over time, British publishers would sometimes re-issue The Silver Locusts contents (lacking both “Usher II” and “The Wilderness”) under The Martian Chronicles title, and The Martian Chronicles contents of the book club edition (lacking “The Fire Balloons”) under The Silver Locusts title. No British edition included all three of these shifting stories.

Back in America, the publishing progression was only slightly less confusing. The wide popularity of the Doubleday first edition persuaded Bradbury’s editors to advise against tampering with the original mix (fifteen stories, eleven bridges). The various Bantam (later Simon & Schuster) paperback editions that kept the Chronicles in print continuously into the twenty-first century made this original mix (still without “The Fire Balloons” or “The Wilderness”) the only version that most readers encountered in the widely read mass-market paperback form.

Meanwhile, a 1963 special Time, Inc., edition gave Bradbury the chance to bring his settled intentions (seventeen stories, eleven bridges) together in a single volume for the first time. In 1973, Doubleday finally brought the two additional stories into a new issue of the first edition typesetting, but this edition was soon out of print. Several limited-printing special editions briefly extended the life of Bradbury’s complete Chronicles, but a major market trade edition reflecting Bradbury’s settled intention has not been available for more than four decades, an absence now remedied by the new Library of America volume.

[Note: Eller’s “Note on the Texts” at the back of Ray Bradbury: Novels & Story Cycles covers the content history of The Martian Chronicles in more detail.]

LOA: Reading Bradbury’s work in chronological order as it’s presented here, it’s startling to see the themes of 1953’s Fahrenheit 451 appear in vivid, miniature form in “Usher II,” a story from a few years earlier that’s part of The Martian Chronicles. Can you discuss why censorship and threats to imaginative freedom had such clear personal significance for Bradbury?

Eller: Ray Bradbury always believed that authors live through their books, long past the end of their lives on Earth. In his view, to burn the book is to burn the author, and thereby destroy the essence of our humanity.

Following World War II, Bradbury sensed a growing intolerance of supernatural tales and other kinds of nonconformist literature in American culture, and he began to write cautionary tales that addressed these concerns head-on. “Usher II,” first published as “Carnival of Madness” in the April 1950 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories, includes one of the best passages he would ever write about the insidious nature of the climate of fear he saw emerging in mid-century America:

They began by controlling books of cartoons and then detective books and, of course, films, one way or another, one group or another . . . there was always a minority afraid of something, and a great majority afraid of the dark, afraid of the future, afraid of the past, afraid of the present, afraid of themselves and shadows of themselves.

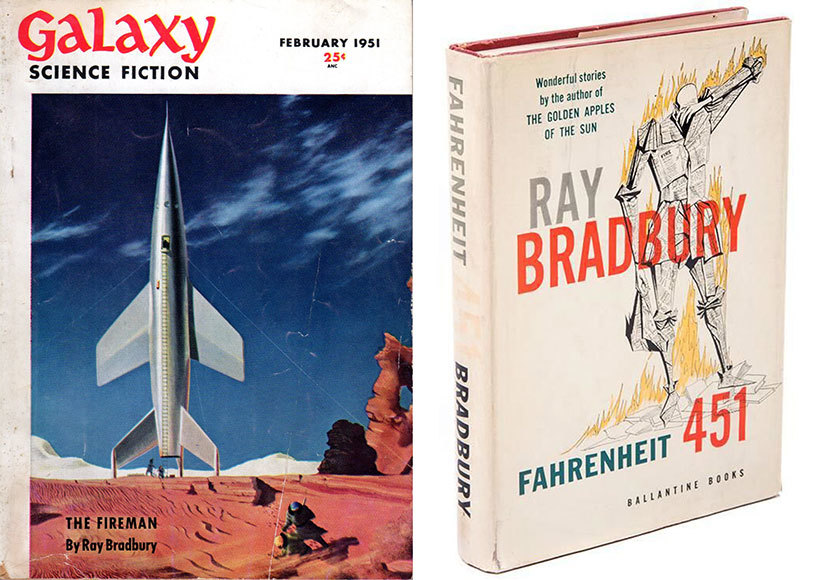

Bradbury wrote perhaps a dozen more stories of this kind during the late 1940s and early 1950s, culminating in “The Pedestrian,” imagining a world where the intoxicating lure of night-time television and other controlling media made it abnormal to step outside and take an evening walk. Bradbury felt that the pedestrian would be an early casualty of a totalitarian society—his pedestrian is intercepted by a robotic police vehicle and quietly eliminated; no one will even notice that he is gone. Even before “The Pedestrian” reached print, Bradbury created “The Fireman” and its young pedestrian Clarisse, who will awaken Fireman Montag to the world of books. She remained a pivotal figure when Bradbury extended “The Fireman” into novel form as Fahrenheit 451.

LOA: The citizens in Fahrenheit 451 anesthetize themselves with wall-size TV screens that can be seen as anticipating the rise of streaming services by several decades, and they also shut themselves off with “ear thimbles” that sound remarkably like the ear buds that are ubiquitous today. Do you care to comment on Bradbury as cultural prophet?

Eller: At least one of these innovations almost beat Fahrenheit 451 to publication. Two creative blazes fueled Bradbury’s vision of an inverted world where firemen set fires instead of extinguishing them. The first, during the summer of 1950, resulted in a 25,000-word novella subsequently published in the February 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction as “The Fireman”; the second burst, steadily burning through the early summer of 1953, transformed that novella into the enduring 50,000-word novel Fahrenheit 451. In the interval between these efforts, he discovered that one of his fictional devices—the “sea-shell” ear thimbles that replace reality with mesmerizing entertainments—had just emerged in his own time as transistor radio ear plugs. “I thought I had raced ahead of science, predicting the radio-induced semi-catatonic,” Bradbury wrote in the May 2, 1953, issue of The Nation. “In the long haul, science pulled abreast, tipped its hat, and fed me the dust.”

The ear thimbles, multiple wall TV screens, interactive streaming services, and automated bank machines found in Fahrenheit 451 were not unique to Bradbury’s fiction, but it was more culturally prominent—and hence more enduring—here than in the more technically-imagined examples found elsewhere in mid-century science fiction. He was not technically sophisticated, and his own sense of the future focused more on the human factor than the technology itself. Bradbury, like Aldous Huxley, was far more interested in the notion framed by Juvenal in first-century Rome: “Who watches the watchers?” Bradbury did not mistrust technology; rather, he mistrusted those who control these technical and scientific wonders. He saw his role not as a predictor of futures, but as a preventer of certain futures where accountability was obscured by power. Like Clarisse in Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury felt that the vital question in any human endeavor was not “how,” but “why.”

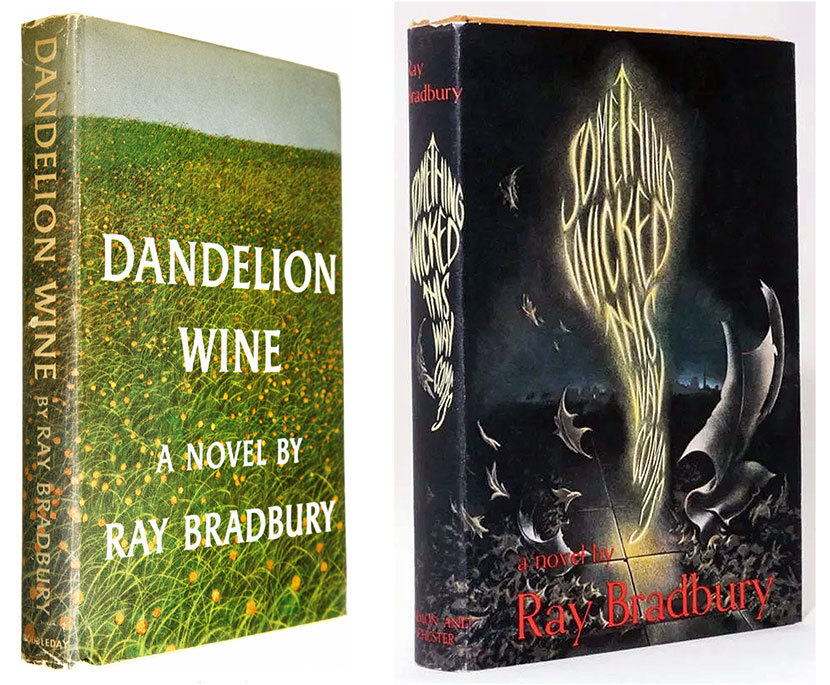

LOA: Dandelion Wine (1957) and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962) both center on youth and are set in the fictional Green Town, a stand-in for the Waukegan, Illinois, of Bradbury’s own boyhood. It’s common to read them as a kind of diptych, with Something Wicked serving as the earlier novel’s darker twin. How much validity is there to this reading, and does it enhance our appreciation of the two books?

Eller: Ray Bradbury was first and foremost a teller of tales; like Mark Twain before him, it took Bradbury many years to transition into writing sustained book-length fiction; when he did, the result was often woven from individual short-story variations on similar themes and settings. His rich legacy of “Green Town” memories produced dozens of stories published from the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s, but the novel he was forming from many of these stories remained unpublished for a half-century until a remnant of it emerged as Farewell Summer in 2006. But he was able to extract and bridge some of these stories in 1957 to form Dandelion Wine, focused on the small-town midwestern world of a young boy and his friends during the eventful summer of 1928. Terror is present, but it does not dominate; instead, we see the passing age of innocence, as the dependable world of childhood joy gradually reveals hints of the responsibilities and challenges that time and memory will bring.

Something Wicked This Way Comes grew into a novel from a single 1948 Green Town tale, “The Black Ferris,” a story that Bradbury had held out of all his other story collections as it grew from an unproduced screen play into the 1962 novel that closed out his first two ground-breaking decades as a writer. These terrifying adventures would evolve into Bradbury’s deepest meditation on life, death, and the nature of evil. It is safe to say that Something Wicked is Dandelion Wine’s darker twin, but Dandelion Wine builds on the very same potentialities of good and evil that a careful reader finds in both books. His December 1964 Show magazine interview leaves no doubt of this connection: “So in writing Dandelion Wine, I was doing more than time-traveling fueled by nostalgia. I was picking up and putting down objects which represented Noon and Midnight, good and evil, the vast cry of terror or the easeful sigh of relaxation on a summer evening early.”

LOA: Novels & Story Cycles concludes with half a dozen essays and articles, some of them quite obscure, in which Bradbury reflects on his work. What do these pieces add to our understanding of the four works that precede them in the collection?

Eller: Most of these ancillary selections convey the sheer joy and excitement of writing that underlies Ray Bradbury’s fiction. He always felt that style was based on emotional truth, and these essays touch on the truths behind his storytelling. “A Few Notes on The Martian Chronicles,” published in the West Coast fan based Rhodomagnetic Digest just after publication of the Chronicles, leaves no doubt that Bradbury’s breakthrough book reveals far more about Earth than it does about Mars. Will our unrestrained materialism destroy the resources and life of Mars in the same way that Earth itself has been diminished? Will the pioneers who go to Mars find their dreams, or only a mirror for reflection?

Bradbury’s science fiction was very different from that of his peers, and some critics and writers wondered if Bradbury ever really wrote science fiction at all. Yet he found himself in the forefront of those writers who brought science fiction into the literary mainstream, and it was inevitable that he would write a reflection on why he wrote in this tradition. “Day After Tomorrow: Why Write Science Fiction?” appeared in the May 2, 1953, issue of The Nation, and offers insight into the aspects of the modern world that led Bradbury to contemplate how we might negotiate the encroaching authoritarianism, forced conformity, and conspicuous consumption of the postwar world. This essay appeared just four months before Bradbury published Fahrenheit 451, and it could well have served as preface for that classic cautionary tale.

The very rare pamphlet No Man Is an Island, a Bradbury lecture published in 1952 to help fund the new Brandeis University library, reinforces his lifetime conviction that the “particularly quiet fortress known in our society as a library,” free and open to everyone, provides the foundation for a free and open society. For Bradbury, a library free of censorship and expurgation offers the best chance to fully comprehend where humanity has been, and where it might be going: “To put out your hand, freely, in a library, is to put out your blind hand and touch humanity.” This lecture captures Bradbury’s state of mind on the eve of beginning his transformation of “The Fireman” into Fahrenheit 451.

The final three selections reveal “the story” behind his storytelling, how he came to fashion two enduring novels from memories of his childhood in Waukegan of the 1920s and early 1930s. This was never a rational or self-conscious process, as Bradbury reveals in “Just This Side of Byzantium,” an introduction to later editions of Dandelion Wine: “I blundered into creativity as blindly as any child learning to walk and see. I learned to let my senses and my Past tell me all that was somehow true.”