Born on August 27, 1871, Theodore Dreiser is most remembered for his debut book, Sister Carrie (1900), and his breakthrough best seller, An American Tragedy (1925). Readers and critics think of him primarily as a novelist, although there are only six novels among the two dozen books he published during his life. (Two additional novels, one of which was unfinished, were published after his death in 1945.) His other books include journalism, short stories, poetry, plays, travel writing, memoirs, essays, and social criticism.

“One of Dreiser’s most enduring books,” according to biographer Richard Lingeman, is Twelve Men (1919), a collection of biographical narratives that exemplify “Dreiser’s idea that goodness comes in unconventional guises. Most of the twelve men are the opposite of churchgoing do-gooders; their virtue is natural, uncontaminated by society.” Fictionalized to varying degrees, the twelve sketches depict both good Samaritans and individualists — and a few men who can be seen as both. The first six pieces portray acquaintances whom Dreiser regarded as successful; the final six men became failures in spite of their virtues.

Below we present four past Story of the Week selections from Twelve Men — two from each half dozen. “The Country Doctor” blends anecdotes about two rural physicians in a composite panegyric and “A True Patriarch” is a semi-fictional account of Dreiser’s father-in-law. “The Village Feudists” features a curmudgeonly shopkeeper in the fishing village of Noank, Connecticut, and “W. L. S.” is Dreiser’s tribute to his friend, the illustrator and painter William Louis Sonntag Jr., who died at the age of 29.

A family doctor in Indiana was beloved for his home visits, homely advice, and homespun wisdom.

. . . When the fall approached and they would begin their long flight Southward, he would sometimes stand and scan the sky and trees in vain for a final glimpse of his feathered friends, and when in the gathering darkness they were no longer to be seen would turn away toward the house, saying sadly to his daughter:

“Well, Dollie, the blackbirds are all gone. I am sorry. I like to see them, and I am always sorry to lose them, and sorry to know that winter is coming.”

“Usually about the 25th or 26th of December,” his daughter once quaintly added to me, “he would note that the days were beginning to get longer, and cheer up, as spring was certain to follow soon and bring them all back again.” . . .

Dreiser profiles his father-in-law, an elder statesman in rural Missouri known locally for his charitable nature and ornery eccentricities.

. . . Every Sunday afternoon for years, it was his custom to go the rounds of the indigent, frequently carrying a basket of his good wife’s dinner. This he distributed, along with consolation and advice. Occasionally he would return home of a winter’s day very much engrossed with the discovery of some condition of distress hitherto unseen.

“Mother,” he would say to his wife in that same oratorical manner previously noted, as he entered the house, “I’ve found such a poor family. They have moved into the old saloon below Solmson’s. You know how open that is.” This was delivered in the most dramatic style after he had indicated something important by throwing his overcoat on the bed and standing his cane in the corner. “There’s a man and several children there. The mother is dead. They were on their way to Kansas, but it got so cold they’ve had to stop here until the winter is broken. They’re without food; almost no clothing. Can’t we find something for them?” . . .

The narrator investigates how a once-admired shopkeeper alienated so many of his neighbors, especially the town’s leading citizen.

. . . Writing a letter in the Postoffice one day I ventured to take up this matter with the postmaster.

“You know Mr. Burridge, don’t you — the grocer?”

“Well, I should guess I did,” he replied with a flare.

“Anything wrong with him?”

“Oh, about everything that’s just plain cussed — the most wrangling man alive. I never saw such a man. He don’t get his mail here no more because he’s mad at me, I guess. Took it away because I had Mr. Palmer’s help in my fight, I suppose. Wrote me that I should send all his mail up to Mystic, and he goes there three or four miles out of his way every day, just to spite me . . . .”

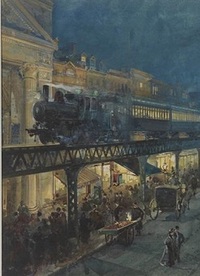

The author hires an artist to illustrate articles in a magazine and discovers a new friend with an astonishing range of interests and hobbies.

. . . He was a member of several engineering societies, and devoted some part of his carefully organized days to studying and keeping up with problems in mechanics.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” he observed, when I marveled at the size and perfection of the model. “I’ll show you something else, if you have time some day, which may amuse you.”

He then explained that he had constructed several model warships, and that it was his pleasure to take them out and fight them on a pond somewhere out on Long Island.

“We’ll go out some day,” he said when I showed appropriate interest, “and have them fight each other. You’ll see how it’s done!” . . .