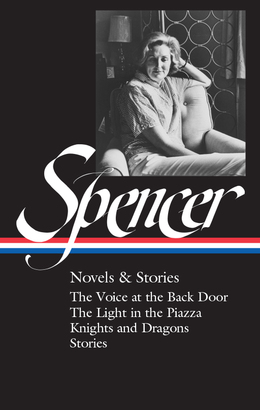

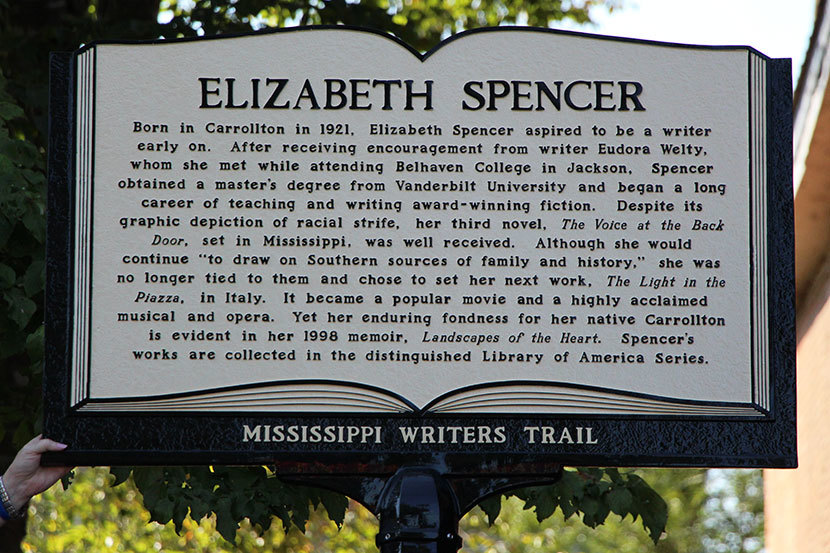

Another major twentieth-century author enters the Library of America series today with the publication of Elizabeth Spencer: Novels & Stories, which collects three novels and nineteen short stories by the Mississippi-born Spencer, who died in 2019 at the age 98. In the following guest post, the book’s editor, Michael Gorra, introduces the novel that is widely considered Spencer’s masterpiece and suggests why it may have been unfairly denied a Pulitzer Prize in Fiction at the time of its original publication.

| Read The Voice at the Back Door |

|

| in Elizabeth Spencer: Novels & Stories |

There are a lot of great first sentences in American literature. “Call me Ishmael.” That’s a good one, and so is John Cheever’s lead to Bullet Park: “Paint me a small railroad station then, ten minutes before dark.” But great first chapters are rare. No reader will soon forget the cinematic first chapter of Elizabeth Spencer’s The Voice at the Back Door (1956). She begins the book with a speeding car, one so thoroughly at home on the gullied red clay roads of mid-century Mississippi that it almost doesn’t need a driver, a car that “dodges the washouts, straddles the ruts, nicks the bumps on the easy corner, and strikes, just at the point of balance, the loose plank on the bridge.” It showers a trio of Black mill workers with dust as it passes, and a couple of white bootleggers figure that its speed must mean something.

Because they recognize the car; everybody does. It belongs to the county sheriff, and then it slides down out of the hills and on to the courthouse square of a small town called Lacey. In a few minutes the officer will drop dead of a heart attack that he’s felt coming for miles. Still, “it had seemed very important to him to reach Lacey alive,” and to anoint his successor, Duncan Harper, a young grocer who was once a football star, and a man who believes a whole lot of things that that Jim Crow sheriff would be shocked to learn.

I didn’t know what to expect when I first pulled The Voice at the Back Door off the library shelves. I didn’t know much more than that Elizabeth Spencer was a Southerner whose best-known book was rather incongruously set in Florence, a short and perfect novel called The Light in the Piazza (1960). That one I’d already read, stumbling on it in a Cambridge bookstore not long after my own first trip to Italy. It’s about a desperate mother who makes a terrible wager on her daughter’s future, and somehow manages to win: a book that captures America’s mid-century moment of confidence, the confidence of a people who thought, however briefly, that they could do anything. But I hadn’t read anything else by her, even though I knew that her short stories were sometimes spoken of in the same breath as those of her friend Eudora Welty. Then a stray reference made me curious. The Voice at the Back Door was supposed to have won the Pulitzer, only somehow it didn’t. Where did I read that, hear that? The details are lost, but it was enough to send me into the stacks.

The novel is set in Mississippi at some indeterminate point in the early 1950s, a rural county that Spencer explores from top to bottom: rich and poor, Black and white, and the old stories that bind them. The soldiers are back from the war, and the Black veterans are impatient. Something’s got to change, and a foreman at the local mill, Beck Dozier, stands as the voice of the title, a man who one night appears all bloody at Duncan’s back door, having just suffered a beating. Then there’s the local bootlegger, Jimmy Tallant. He’s a war hero, and he’s in love with Duncan’s wife. Always has been; this is a town where everybody has known each other for too long, known each other’s business too.

Though some things are never spoken of, and Jimmy is linked to Beck in a way that they can only acknowledge when they meet during the war in an unsegregated English bar. A generation back Jimmy’s father had led a mob that killed Beck’s father and many of Lacey’s other Black men with him. It’s the thing nobody talks about, the history that haunts them all, and haunted Spencer as well. In 1886 there was a similar massacre in her hometown, Carrollton, Mississippi, when over twenty Black citizens were shot at the local courthouse. The bullet holes remained visible until the 1990s, and as a child she always wondered about them, puzzled that she couldn’t get the grown-ups to tell her what had happened.

Spencer wrote most of The Voice at the Back Door in Rome, after using a 1953 Guggenheim to get herself abroad. She was thirty-two and had already published two novels, but Italy changed her world: Italy itself, and the other Americans she found there. Rome was a glitter of excitement, a place full of other writers and artists, and she soon realized that many of the things “I had accepted all my life” now looked “outrageous.” Yet the South had also changed, and in ways that she only discovered when she took her manuscript home in the fall of 1955.

The year before, Brown v. Board of Education had roiled white sentiment throughout the region, spawning what were called the Citizens’ Councils, aka the “uptown Klan,” an organization of clergymen and business leaders who were determined to resist the Supreme Court’s order to end the system of separate but hypothetically equal education. There was, however, an even more pressing issue, and only one county over. Just a few weeks before Spencer’s return, a Chicago teenager named Emmett Till had been abducted and murdered while on a visit to his relatives in Mississippi, killed for having supposedly whistled at a white woman. Spencer immediately got into an argument with her father about the case, one that pushed her toward the realization that she could no longer live in the South, not there, not then. She stayed in Mississippi for just a few days, finished The Voice at the Back Door in New York, and the next year returned to Rome.

The novel depicts the everyday racism of white society, ventriloquizing the spitting vehemence of her characters’ speech. And then Spencer does something more: she describes her own rising generation as one that in private might almost seem progressive, but that in public preached segregation. She names the conscious hypocrisy of the world to which she belonged, in which political expediency could excuse anything. Some white readers branded her a traitor, and her Vanderbilt teacher Donald Davidson, a Confederate apologist, refused ever to speak to her again. The next year the judges for the Pulitzer Prize recommended The Voice at the Back Door for the award in fiction, while noting that they considered the year as a whole undistinguished. It wasn’t, not when the other books published in 1956 included Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, novels that have their own proud place in the Library of America. But the Pulitzer board decided to make no award, and that decision that has never been adequately explained.

Spencer knew the book had been in the running, but she didn’t know how close she had come to that career-making prize until she was in her seventies, when the letter carrying the judges’ recommendation came to light. Her published comments about the matter are gracious, but it’s hard not to see the board’s decision as a political one. I suppose it’s possible that the board believed she hadn’t gone far enough—but it seems more likely that they feared she had gone too far. She later wrote that in her time abroad “a precipitate moment had come and gone” in the history of her home state. The cautious, ever-violent, and yet somehow stable Mississippi that she had created in Italy already looked outdated, as though her work had been outstripped by the headlines. Jim Crow might still appear unshakeable, but Brown had changed things. So had Emmett Till’s murder, and the Montgomery bus boycott that began in December 1955. Those events threatened white hegemony, and in consequence the white South became more twitchy and savage and threatening than ever, a place even worse than she had shown it.

That’s how it might look to us now. But for that particular troubled moment Spencer had indeed gone too far. I think the Pulitzer board was afraid, and without any written record of their deliberations I’ll stick to that. They blinked. They were afraid the prize might spark off an already explosive situation, with white supremacist violence on the rise throughout the region; a region that would no longer tolerate dissent. William Faulkner spoke for many white Southern moderates when he said that the Civil Rights movement should “go slow” lest it provoke a reaction, and I can’t help but wonder if the Southerners on the Pulitzer board—moderates themselves, who with time would move left—might have offered a similar counsel.

Gimlet-eyed and entirely absorbing, The Voice at the Back Door stands as the finest novel by a white writer of its era to deal with the world of Jim Crow. And by that I mean it’s better than either Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1948) or Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). Both Faulkner and Lee used children as narrators, and it would be worth asking why, why they needed that position of relative innocence. Spencer doesn’t, and the advantage is all on her side. The Voice at the Back Door is a book for and about grown-ups, in which every character is compromised, Duncan and Beck included. It is a larger and more knowing novel than its more famous peers, more politically savvy and shrewder about the full complexity of its society. More exciting too, with a swiftly moving plot that’s as limber around the curves as that old sheriff’s car; and a whole lot sexier besides. It should long ago have been recognized as an American classic, and if the Pulitzer board had done the right thing it probably would have been. I hope this Library of America edition will give it the stature it’s deserved all along.

Michael Gorra is the Mary Augusta Jordan Professor of English at Smith College, where he has taught since 1985. He is the author of The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War and Portrait of a Novel: Henry James and the Making of an American Masterpiece, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the Biography. In addition to the Library of America edition of the novels and stories of Elizabeth Spencer, he is also the editor of Norton Critical Editions of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury.