This Black History Month, we pay special tribute to a remarkable nineteenth-century Black poet whose literary tools were not paper and ink but clay and kiln.

David Drake (c. 1800–c. 1870s) was an enslaved potter who defied convention not only by making “larger and heavier wares than anyone else” (as Drake scholar Aaron de Groft put it in a 1998 essay), but also by adorning many of his stoneware products with unique personal inscriptions—including short, original poems of rhyming couplets. Sometimes the lines simply described a particular pot’s function or owner: “When you fill this jar with pork or beef / Scot will be there to get a peace”; other times, they gestured at and subtly critiqued the oppressive institution of slavery in the United States: “Dave belongs to Mr. Miles / where the oven bakes & the pot biles.” Michael A. Chaney, Professor of English and Vice Chair of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College, has written that Drake’s “hybrid assemblages of material and literary expression complicate our understanding of slave authorship.”

Testifying to the growing acknowledgment of Drake as a literary figure, over twenty of his stoneware inscriptions appear in the new Library of America anthology African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song, edited by Kevin Young.

Although Drake is estimated to have produced tens of thousands of vessels in his lifetime, little more than a hundred survive with his engraved handwriting. His pottery has appeared on Antiques Roadshow and was the subject of an award-nominated 2013 documentary. In November 2020, one of his pots sold for $369,000—a new high for Drake’s work, beating a record figure set only six months earlier.

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of Drake’s unique literary endeavors is that his unabashed display of creativity and literacy was actually illegal—and thus incredibly daring. South Carolina’s 1740 Negro Act, still in effect during Drake’s lifetime, prohibited enslaved people from reading or writing, with punishments ranging from beatings and mutilation to outright execution. Yet Drake confidently scrawled his voice and verse into the public sphere—beginning in 1834 and continuing at least into the 1860s— combining courage and pride with craftsmanship and a rare verbal flair.

While biographical accounts sometimes differ when it comes to David Drake’s early life, we know that he was born around 1800, almost certainly into slavery, and probably near the South Carolina town of Edgefield, an important regional producer of stoneware pottery. In his formative years, Drake was forced to labor for his various white slaveholders both as a newspaper typesetter and as a potter—labor that exploited Drake’s skills to further the wealth of those slaveholders. It was his merging of these two trades that would brand Drake’s pottery as truly exceptional.

In 1834, Drake produced his first pot known to have included an inscription, which read: “put every bit all between / surely this Jar will hold 14”—a reference to the pot’s holding capacity in gallons. He would only begin signing his wares in 1840, around the time he stopped inscribing them with verse for about seventeen years—possibly a precaution following an 1841 Georgia slave rebellion that left enslaved people under heightened suspicion and scrutiny. But in 1857, he resumed the practice more boldly than ever.

One jar, dated August 22, 1857, bears the inscription: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all—and every nation.” Throughout his life, Drake had witnessed firsthand the splintering of enslaved families, possibly even his own, as slaveholders sold their servants, passed them to different family members, or left them to be divided upon their own deaths as pieces of their estates. Thus, Drake’s words stand as an enslaved person’s indictment not just of the widescale institution of slavery but of his particular slaveholders as well.

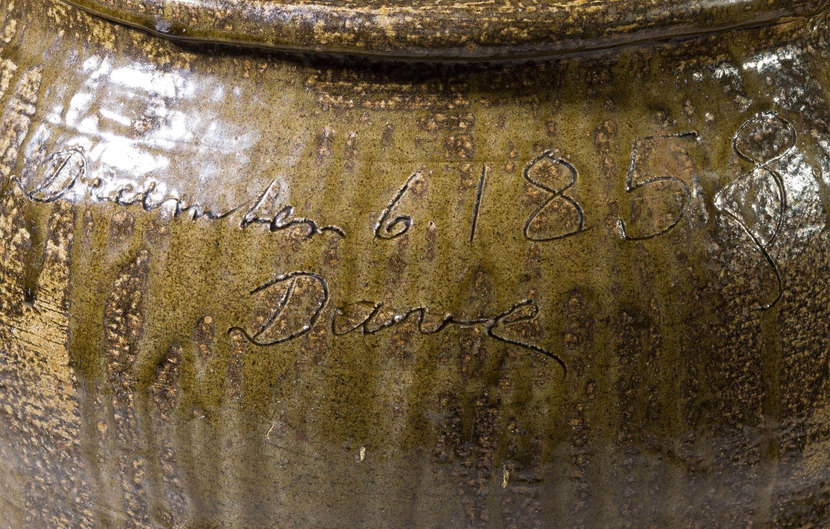

Another vessel, dated December 6, 1858, subtly remarks on slaveholders’ cruel practices of gifting or leasing enslaved people out at Christmastime or on New Year’s Day: “Nineteen days before Christmas Eve— / Lots of people after its over, how they will greave…” Like many of Drake’s poems, these lines carry a double meaning that may have protected him: to most readers, they would have characterized the sadness at the passing of the holiday season, but for Drake and his potential enslaved readers, the lines offer a painful critique of the Christian institution of slavery in the United States.

Drake himself won his freedom by the end of the Civil War. He was listed in the 1870 census as a turner, but there the record stops, suggesting his death in the 1870s. Yet today, nearly 150 years after his likely passing, “Dave the Potter” is more visible than ever—as evidenced by his appearance in African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song, and, just this week, an Instagram post from the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Library of America’s anthology African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song is the centerpiece of Lift Every Voice: Why African American Poetry Matters, a national public humanities initiative made possible with support from The National Endowment for the Humanities, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Emerson Collective. For more details, please visit the companion website, which showcases video readings and commentaries, along with a timeline of African American poetry, archival audio and video, photos and biographies of the poets, a reading group guide, and more.