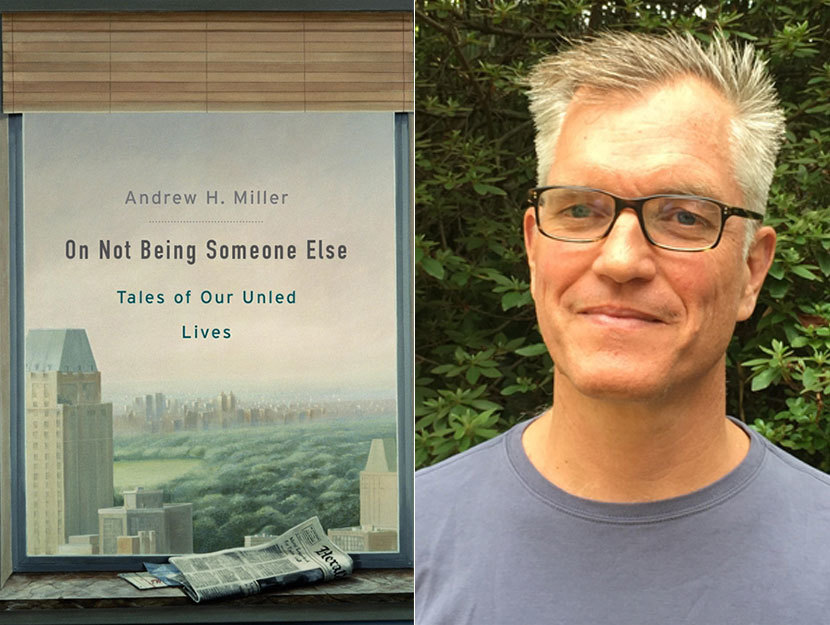

In a year when so many people are conscious of the lives they could be leading under different circumstances, Andrew H. Miller’s On Not Being Someone Else: Tales of Our Unled Lives (Harvard University Press) is an unusually apt critical study.

Starting from the premise that nearly all adult human beings at some point in their lives become conscious of paths and possibilities left unexplored, Miller traces the ways in which literature both amplifies and magnifies this near-universal sensation. As he writes in his introduction: “What, exactly, is the relationship between the lives we haven’t led and the stories we read?”

On Not Being Someone Else is particularly attentive to this theme’s prominence in American literature, with Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” and Henry James’s “The Jolly Corner” serving as essential touchstones. In the following interview with Library of America Editorial Director John Kulka, Miller ranges from those classic works to a certain equally foundational Frank Capra film to the ways in which African American writers have found a special relevance in the concept of unled lives.

Andrew H. Miller is Professor of English at Johns Hopkins University and the author of Novels Behind Glass: Commodity Culture and Victorian Narrative (2008) and The Burdens of Perfection: On Ethics and Reading in Nineteenth-Century British Literature (2010).

John Kulka, Library of America: Andrew, I have looked forward to this book as much as any other this year. At its center is a fascinating, haunting premise: that we walk alongside our unled lives, often painfully aware that but for the choices we have made in life (good or bad), circumstances, or turns of events things might have been very different. We might have been, well, someone else. These unled lives elicit a range of emotions but frequently haunt and trouble our sense of self. You argue this sense of our own unled lives is one of the great abiding themes and preoccupations of modern literature. Can you say a bit more for our readers?

Andrew H. Miller: Sure. When I first started to think about unled lives—the lives that you might have led and the person you might have become if your chances or choices had been different—I was struck by how resonant a topic it was for so many people. I talked to friends and strangers from all walks of life. They told me their own stories about the careers they hadn’t pursued, the marriages they hadn’t entered, and their experience as parents or as people without children. Sometimes they became a bit dreamy or muted while they talked to me. It’s an important theme, then, simply because it matters to people.

But as I did my research, I also came to see that writers seemed to be interested in unled lives with special intensity. Why should that be, I wondered. What’s the relation between the lives we haven’t led and the lives we read about? The answers, I discovered, are in part social and historical. As the number of paths available to people has increased over the past couple of centuries, the number of paths that they’ve not taken has of course increased as well. These paths untaken now shape the paths actually taken, and the people taking them. We have come to think, as the anthropologist Clifford Geertz puts it, that “we all begin with the natural equipment to live a thousand kinds of life but end in the end having lived only one.” We each are one person amid many roads, only one of which we’ve taken. And this situation, it turns out, offers a great deal to writers.

LOA: Let’s continue with the metaphor of roads or paths: you begin your book with a discussion of Robert Frost’s still untarnished poem “The Road Not Taken” because it so poignantly captures the experience of “what if”—what if we had taken the other road, how would our lives be different? But it is as you say in your introduction really a poem about resignation. Would you say something more about this for our readers? You call it the “classic poem” about unled lives. Why?

| Read “The Road Not Taken” |

|

| in Robert Frost: Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays |

Miller: I hadn’t really studied Frost’s poem for years, and was a bit wary of it. Its very familiarity made me worry that my topic was old news—something we already knew all about. But when I actually sat with the poem for a while I saw that, for all its well-fingered familiarity, it’s a mysterious piece of writing, spare and extreme. And, as I continued to study it, I saw that it provided the fundamental shape for all the stories I had been interested in. A traveler pauses, looks back, sees two roads behind them, and compares those roads. One person, two roads, retrospection, and comparison: all the difference. Although often varied, these are the basic elements of the stories we tell about our unled lives. It is a rudimentary story form, but one that provides a lot to a writer: a central, reflective consciousness; a forward moving plot, a dramatic, forking moment of choice or chance; and a rich range of emotions, including regret, relief, envy, sympathy, wistfulness, rue, gratitude, remorse. . .

This story form brings with it an aesthetic ideal as well. Writers fascinated by our unled lives typically see their own works as shadowed by their alternatives, that is, by the paths they didn’t take, the works they didn’t write. Poems and novels and stories and films have their own unled lives; they’re accompanied by possibilities unrealized. In this picture of art, a successful work is one which no further changes could improve, for no alternative is better. It’s an entrancing ideal; it suggests that the artwork might leave us desiring nothing. But it also suggests that successful works of art leave the debris of discarded possibilities behind them. It sees in beauty something lost, and makes of loss something beautiful.

The resonance of unled lives for people, the rich materials they offer for artists, and the aesthetic ideal they provide: these things have made unled lives a major theme in modern literature and film.

LOA: William Hazlitt said that although we might wish to possess attributes of some other, envied person—their good looks, their intelligence or creativity and so forth—no one ever wishes to be another person. We want instead to be in possession of these things but somehow still fundamentally ourselves. I think of this comment in connection to a moment in Henry James’s short story “The Jolly Corner,” when the main character finally confronts the ghostly figure who represents his unled life in America. The brutality of the figure shocks him. There are limitations, then, on what we are willing to accept as a possible unled life?

| Read “The Jolly Corner” |

|

| in Henry James: Complete Stories 1898–1910 |

Miller: Yes, absolutely. There’s been a raft of work by psychologists concerned with the limits of our imagination of alternative pasts. Some of this work is quite ingenious. For instance, one study argued that someone who finishes third in a race is likely to be more satisfied than someone who finishes second if three medals are awarded: the third-place finisher is glad she didn’t finish a medal-less fourth, while the second-place finisher is disgruntled because she didn’t get first. Philosophers from Aristotle through David Lewis have also puzzled over both the logical and psychological limits of our imagination. As Leibniz famously argued, what’s the sense in wanting to be the King of China? Wouldn’t it mean that God had at one moment created a new King of China and destroyed you?

Literature uses its own tools to test these limits. Take, for instance, the invitation fiction often offers to identify with characters. Let me use an example that isn’t from American literature. When we open Jane Austen’s Persuasion the first thing, we encounter is a man opening a book, and so we are encouraged to see ourselves in him: he is doing what we’ve just done ourselves. But we quickly learn that this man, Sir Walter Elliot, is a fatuous ass. The book he’s taken down is the Baronetage, which describes the history of aristocratic families, and he’s opened it to his favorite page, the one on which he himself appears. Austen, with her wonderfully feline wit, is both inviting us to see her characters as possible versions of ourselves and discouraging us from doing so—inviting us in and warning us off all at once.

“The Jolly Corner,” which is the classic story of unled lives as “The Road Not Taken” is the classic poem, tests these limits more or less continuously. Spencer Brydon finally does reject his unled life and does embrace the life he’s leading with the tirelessly patient, alert, intelligent woman who has been his companion, Alice Staverton. But the story ends when he does. I take this to show that James is most interested not in what it is to accept the life you’ve led, but in the process of comparing that life with lives you might have led; once that process ends, his story is done. Like other writers, he’s interested in this comparison as a way of making or finding meaning in a life. One way we figure out who we are, that’s to say, is by comparing who we are with who we might have been. And the resources of literature make it our most powerful way to make this comparison.

LOA: Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life ends with the powerful injunction to give up fantasies of unled lives. It resolves into acceptance and understanding, which it makes it a perfect holiday movie. I’m thinking of that film in relation to another—because I suppose it’s a movie I have rewatched recently—which seems so different in its depiction of unled lives: Jacques Demy’s sublime The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. There is a powerful sense of both contingency and irrevocability in that film. Guy and Genevieve, the principal characters, who have gone their separate ways, are briefly reunited in the film’s last scene. Guy seems happy, he seems to have wound up with the right woman, but why does that ending seem like such a tragedy? Perhaps “tragedy” isn’t the right word, but it’s a bewildering ending.

Miller: I’m delighted that you mention Cherbourg, which I hadn’t thought of. One of my goals in writing this book was to leave it open for readers to extend—that is, to invite readers to think up examples from writing (or their own lives) which add to and perhaps complicate the story I’ve told.

Demy’s movie incorporates several themes I found elsewhere: the choices and chances of marriage and career; the pressures of economic need; the desire to travel; and the role of parenting and children. From the moment a second woman and a second man appear on screen, we see that this movie will describe an extended fork in its narrative road: we’ll watch as Genevieve and Guy slowly do—or do not—get married to each other. But, as you say, the emotional core of the movie comes at its end: watching that final scene we can almost see the couple Genevieve and Guy would have become, had they stayed together. All this fits squarely within the genre of unled lives. To see what it adds to that genre, we’d have to think more carefully about Demy’s extraordinary use of singing and color, which make the characters seem from the beginning to exist in another world from our own.

LOA: You call It’s a Wonderful Life the “classic film” about unled lives. So, the classic poem is Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” the classic story James’s “The Jolly Corner,” and the classic film Capra’s holiday favorite. To be clear to our readers: you are not exclusively concerned with American literature and film. But is there something particular about American lives and culture that makes us so fascinated with unled lives?

Miller: Generally speaking, the isolation of individuals in America, and our insistence on narratives of individual progress, make thoughts of unled lives seem natural to us. And the more recent treatments of the topic I have found have, in fact, tended to be by Americans: Sharon Olds, Carl Dennis, Claire Messud, Jenny Offill, Jane Hirschfield, Meg Wolitzer, and others. For Philip Roth, whom I mention only in passing, unled lives have been a recurrent preoccupation.

But there are more particular ways that America has proven congenial to unled lives. To take an especially powerful instance, the literature of racial passing, spurred by American racism, has led African American writers to imagine unled lives with special intensity. The aspirations and brutal ironies of stories by James Weldon Johnson, Jesse Redmon Fauset, and Langston Hughes, among others, often speak of what is not. And, more recently, Wes Moore’s bestselling memoir, The Other Wes Moore, recalls the longstanding interest of Black American writers in their unled lives, and their continuing resonance.

LOA: Thanks, Andrew. That seems like the perfect place to end this interview.