By Geoffrey O’Brien

Good guys turn bad and bad guys turn strangely sympathetic with disconcerting frequency in the Cinemascope adaptation of Oakley Hall’s subversive meta-Western.

In 1959 Westerns rode high. On television, Gunsmoke, Maverick, Have Gun Will Travel, Wagon Train, and Bonanza topped the ratings, while moviegoers could choose among Hollywood releases like Rio Bravo, Ride Lonesome, The Wonderful Country, The Hanging Tree, and Day of the Outlaw—movies whose range of mood and approach showed how varied the genre had become. Only such a moment could have predisposed a major studio, 20th Century Fox, to rush into production with a large-scale film of Oakley Hall’s novel Warlock, published the year before. It had been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, but Hall’s book would not ordinarily have seemed obvious movie material. It took the generic archetypes of the genre—marshal, gunslinger, gambler, whore, pious townsfolk, reckless outlaws—but twisted them around and mixed them into the prototype of all future meta-Westerns, darkly funny, deliberately extreme, and steadily subversive. The story of the Old West became a convoluted diagram of factional struggles and cycles of reprisal with no easily digestible moral or all-resolving ride into the sunset.

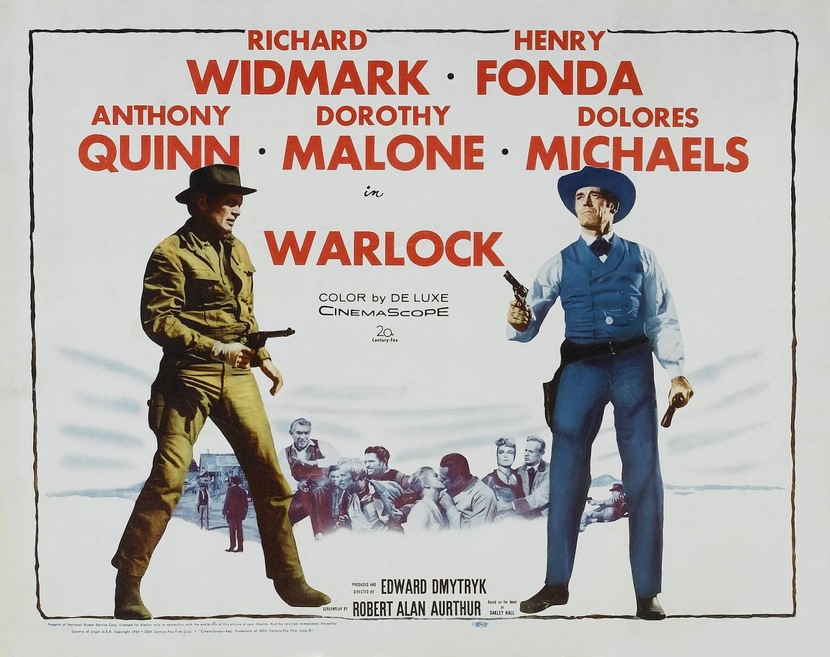

It was inevitable that a movie version would make some compromises with such a source. If nothing else, the sheer profusion of Hall’s wildly elaborated plot needed to be drastically pared, the book’s rambunctious bawdiness toned down, its underlying pessimism softened just a little. The real surprise is how deftly Robert Alan Aurthur’s screenplay manages to translate Hall’s vision into the mode of a Cinemascope epic in a classic mode, with its array of familiar faces (Henry Fonda, Richard Widmark, Anthony Quinn, Dorothy Malone), its heapings of rugged Utah landscape, its main street lined with hitching posts, saloons, and hardware shops, its reenactment of the expected stagecoach holdups and main street showdowns.

Director Edward Dmytryk’s penchant for overarching high-angle perspectives gives the action an air of ritual formality. The cinematography of Joe MacDonald—fresh from extraordinary collaborations with Samuel Fuller (House of Bamboo) and Nicholas Ray (Bigger Than Life)—brings out riches of color and texture that give the town and its arid surroundings an otherworldly iridescence. There’s a moment early on when vigilantes Clay Blaisedell (Fonda) and Tom Morgan (Quinn) are approaching the town they have been hired to bring under control. Morgan remarks: “There it is, Clay: Warlock,” and they ride forward to peer intently down at—a particularly attractive matte background painting filling most of the wide frame. The loveliness of the shot triumphs over the fakery of the optical effect, almost as if to announce that they are entering transfigured ground in keeping with the witchy implications of the town’s name.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s & 50s |

By the time we get to that point we have already had a glimpse of Warlock’s unstable realities, as a band of lawless cowboys led by the borderline psychotic Abe McQuown (Tom Drake) rides into town and calls out the hapless marshal, pelting him with dirt, cutting his saddle from under him, and singing mockingly as he rides desperately away to avoid getting shot down. A little later a barber is shot dead for having nicked one of the cowboys while shaving him. In short order the frightened shopkeepers have hired the notorious Blaisedell, with his gold-handled Colts, to stop the violence, a common enough scene in ’50s Westerns, with the expected objections: “You’re using anarchy and murder to try to prevent anarchy and murder!” The orphaned Miss Jessie, the piano-playing “angel of the miners” (Dolores Michaels), makes a plea for a nonviolent world.

We seem to be in the familiar territory of a law-and-order parable along the lines of High Noon or The Tin Star, but the precise moral dividing lines begin to blur fairly rapidly as good guys turn bad and bad guys turn strangely sympathetic with disconcerting frequency. Factions open up within factions; law-abiding citizens turn into a lynch mob; the cowboys have one obvious malcontent among their number; the pulp pamphlet in praise of Clay Blaisedell is matched with another such pamphlet painting a darker picture of his partner Tom Morgan, gambler and entrepreneur of the peripatetic establishment The French Palace.

At the center of the ambiguity is the odd couple of Blaisedell and Morgan, fearsome hired guns who cohabit in an atmosphere of hedonistic luxury, and in their early scenes seem to spend much of their time fussing over their elegant attire, sharing sips of fine whiskey, and admiring the new artwork and drapes with which Morgan has decorated their temporary quarters. As played by Fonda, Blaisedell is a philosophical sort of gunslinger with a taste for wry paradox, while Quinn’s Morgan—maybe his best role ever—is virtually his shadowy twin, cynically realistic where Blaisedell pretends to high principles in the matter of extrajudicial killing, a misogynistic sometime pimp (as one deftly placed line of dialogue makes clear) where Blaisedell is a model of gentlemanly courtesy. The clubfooted Morgan devotes himself to Blaisedell’s welfare because “he’s the only person, man or woman, who looked at me and didn’t see a cripple.” Such psychologizing dialogue has a late ’50s ring, but what Fonda and Quinn do with the characters they are given is something to see, as their mutual understandings shift and coil around from moment to moment, moving toward an inevitable cataclysm.

Mutability is Warlock’s through line. No one stays the same for long. As people dare each other to show who they really are, it turns out that none are quite clear on that score. Dorothy Malone as the vengeful Lily Dollar is animated by an understandable righteous fury, but it turns ugly as she mocks Quinn’s disability. Widmark as Johnny Gannon starts out as a member of the cowboy gang, switches sides, and is torn down the middle as he watches Fonda gun down his younger brother in an extraordinary showdown in which shooter, victim, and helpless witness are all on the verge of tears. Widmark is the closest thing the film has to an unvarnished hero, but he is also guilty of participating in a massacre of Mexicans who attempted to retrieve cattle rustled by the cowboys: “We killed ’em all. Thirty-seven of ’em . . . it was kind of like a dream. . . . Firing down into the canyon until there wasn’t nobody left to shoot.” Even the violent cowboys, however spellbound by their paranoid commander, harbor an evidently sincere attachment to the cause of liberty: “This is a free territory!” The jarring transformations of character are marked by not one climactic showdown but three of them, each enacting a distinct drama. The last of these ends in a literally fiery funeral service presided over by a nearly deranged Blaisedell, with Henry Fonda revealing a scarier dimension of his screen persona than he had shown until then.

Some get guiltier as they go along, others try to make up for the guilt they’ve already acquired, almost nobody can claim innocence. The vigilante justice dispensed by Blaisedell and Morgan runs up against the self-proclaimed Regulators declaring resistance under the aegis of the Cowboys’ Council for the Self-Protection of San Pablo. As the cowboys’ humorously inclined herald Curley (DeForest Kelley, in a cameo that almost steals the film) points out to Blaisedell, in a line that gets to the essence of Oakley Hall’s novel: “You see how it could go back and forth and forth and back for all time.” That theme must have resonated for Dmytryk, whose string of 1940s hits (Murder My Sweet, Cornered, Crossfire) was followed by the debacle in which he was sentenced to prison as a member of the Hollywood Ten, fled to England, and then eventually returned to the U.S. to serve a brief imprisonment and name names as precondition for resuming his career. In any event, Warlock (which he also produced) is the finest of his post–Black List films, and a culminating glory of the ’50s Western.

Watch: Original trailer for Warlock (2:48)

Warlock (1959). Directed by Edward Dmytryk. Written by Robert Alan Aurthur, from Oakley Hall’s novel. With Henry Fonda, Anthony Quinn, Richard Widmark, and Dorothy Malone.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video (with Starz)

Geoffrey O’Brien, former Editor in Chief of Library of America, is the author of twenty books of poetry and nonfiction, including The Phantom Empire and Sonata for Jukebox. His most recent titles are Where Did Poetry Come From: Some Early Encounters (published this spring by Marsh Hawk Press) and the poetry collection Who Goes There (forthcoming from Dos Madres Press).