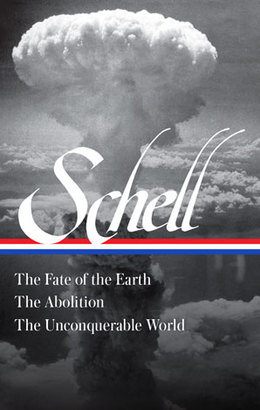

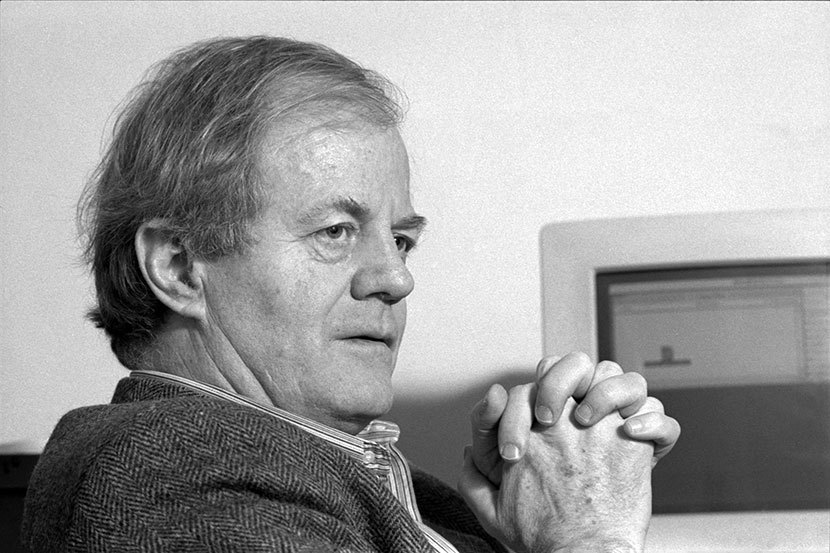

Published by Library of America this spring, Jonathan Schell: The Fate of the Earth, The Abolition, The Unconquerable World brings together three classic works that both illuminate, unforgettably, the nuclear threats our civilization continues to face and envision a way forward to peace. Brave, eloquent, and controversial, they are the essential books by the journalist and thinker whom New Yorker editor David Remnick eulogized as “an essential political writer” when Schell died in 2014.

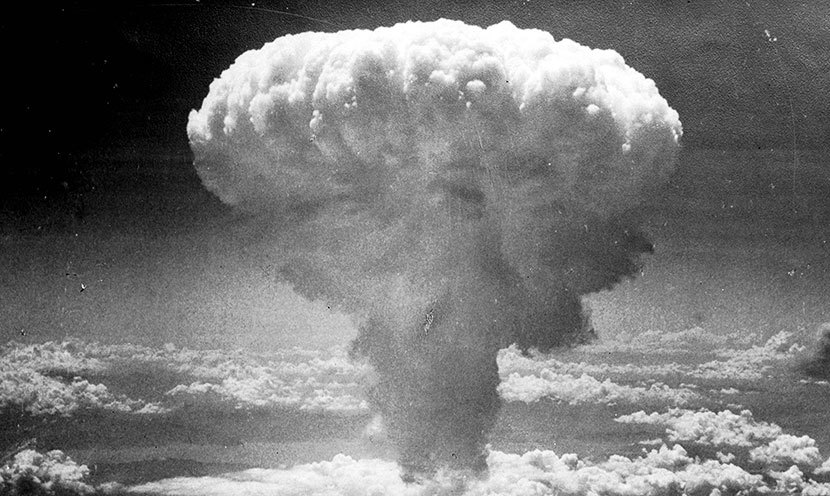

Library of America’s Schell volume arrives just prior to the seventy-fifth anniversary of three foundational events of the nuclear age. The first atomic detonation took place at the Alamogordo Test Range in New Mexico on July 16, 1945; the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6; and it dropped a second nuclear bomb on Nagasaki on August 9.

The book’s editor is Martin J. Sherwin, one of America’s leading writers on nuclear history and the author of A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and Its Legacies; the Pulitzer Prize–winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of Robert Oppenheimer, written with Kai Bird; and, most recently, Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis. A professor emeritus at Tufts University and University Professor of History at George Mason University, he divides his time between Washington, D.C., and Aspen, Colorado, and answered our questions via email.

Library of America: When Jonathan Schell died in 2014, Bill McKibben said of The Fate of the Earth: “In a way that’s hard to imagine in our fragmented media age, his essay mattered: it played an outsized role in catalyzing the nuclear-freeze movement, which in turn played an outsized role in making nuclear war unthinkable.” What made The Fate of the Earth such a successful piece of advocacy?

Martin J. Sherwin: Sometimes facts matter, especially when they are presented clearly and in a time of receptivity. As a writer Jonathan combined masonry with artistry. Each fact was a brick that he carefully connected with other bricks using the finest mortar, his elegant prose that compelled readers to take the facts seriously. He did this in his books on the Vietnam War, on Nixon, and most effectively in The Fate of the Earth, which made it crystal clear exactly how a nuclear war would eliminate the human species.

LOA: The Abolition appeared in the spring of 1984, just two years after The Fate of the Earth. How does that book extend or build on the argument of its predecessor?

Sherwin: The Abolition confronted complaints that The Fate of the Earth discussed the consequences of a nuclear war but did not offer a roadmap to abolition of nuclear weapons, the most difficult of political journeys. It was an attempt to deal with the reality of nuclear deterrence in a creative way. Decades later Jonathan’s thinking underpinned the calls for nuclear abolition by “the gang of four” (George Shultz, William Perry, Sam Nunn, and Henry Kissinger) who came around to Schell’s view that nuclear weapons posed unacceptable dangers. It was also one of the starting points for Global Zero, a movement that has been sustained on college campuses. Perhaps it even inspired President Barack Obama’s speech on April 5, 2009, in Prague calling for the eventual abolition of nuclear weapons.

LOA: Rebecca Solnit has praised The Unconquerable World as “a talisman and key text . . . that goes beyond the more pat versions of what nonviolence is and why it matters.” How does Schell transcend those more familiar appeals?

Sherwin: I don’t know what Rebecca Solnit means by the “more pat” versions of nonviolence, but I think I have a good understanding of Jonathan’s view. At his core, Jonathan was a philosopher. He was deeply concerned with human behavior and its unintended unhappy consequences. He did not offer a vision of a perfect world, because he understood that human thinking is fundamentally flawed. The instinct for violence being perhaps chief among those failings. In The Unconquerable World he exposed how our violence–bias has consistently worked to our disadvantage and how a nonviolence–bias would serve us far better. It was not an argument for absolute nonviolence (perhaps that’s Solnit’s “more pat” version). It was an argument for the need to develop a bias in favor of nonviolence.

LOA: An excerpt from Schell’s The Military Half, his 1968 account of American bombing in Vietnam, appears in Library of America’s Reporting Vietnam anthology. Is there a through-line from Schell’s Vietnam reportage to the three books in this volume?

Sherwin: The first part of my answer to this question is in my response to your first question above. To that I would add that Jonathan was both emotional and disciplined. As a writer he understood that he could be most effective by describing photographs of the human condition, writing like a photographer who saw what others missed. He was a keen observer and a talented relater of human behavior. What was happening in Vietnam, and how awful it was, led him to create scenes of the horrors that were as vivid as photographs. To see this most clearly, read his first book, The Village of Ben Suc (1967).

LOA: The Fate of the Earth and The Abolition emerged from, and contributed to, a historical moment in which the arms race and disarmament were major, mainstream political issues, and a matter of urgent concern for many. With at least several countries apparently having decided arms control is an anachronism, where are we now, in 2020?

Sherwin: If the Chinese calendar has a “Year of the Moron,” 2020 should carry that designation. How can anyone know “where are we now?” We could be at the edge of the abyss in every sense, nuclear destruction included. Or we could be approaching a crossroad that, if we choose correctly, will lead us back to a measure of sanity. The world that we inhabit was not imposed upon us by a mysterious force. We brought it upon ourselves by our arrogance, and our neglect and our domestic and foreign policies. In a deep sense those were the subjects Jonathan confronted. I think Jonathan would ask whether we have learned the right lessons.

LOA: In the words of a recent New Republic review of this collection, Schell “believed nuclear war was the ultimate ecological issue” and environmental concerns become increasingly prominent by The Unconquerable World—indeed, he was even planning a book on climate change at the time of his death. What inspiration can today’s climate change activists take from these books?

Sherwin: Pay attention to the facts, think deeply about them, write clearly, and understand that you have to deal rationally with your opponents if you are going to persuade a sufficient number of your compatriots that you are right.