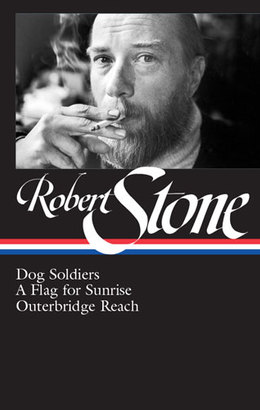

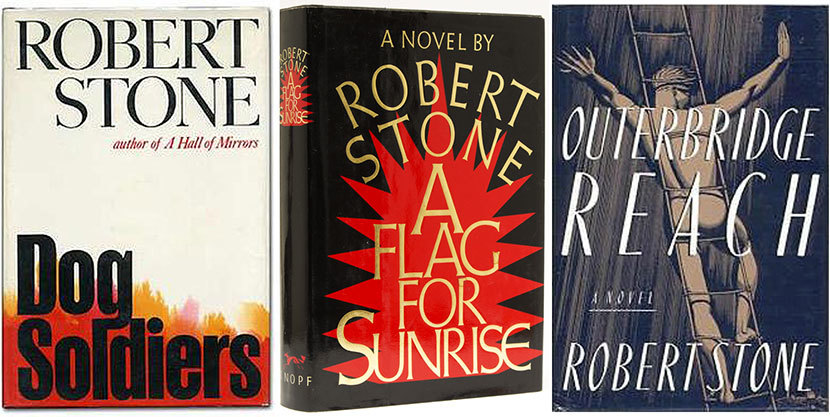

A contemporary master enters the Library of America series this spring with the publication of Robert Stone: Dog Soldiers, A Flag for Sunrise, Outerbridge Reach, which collects three major works by the novelist whom Joyce Carol Oates eulogized as “a great American writer in the tradition of Melville, Hawthorne, Dreiser, Dos Passos and Hemingway” when he died in 2015.

The new LOA volume is edited by Stone’s fellow novelist and longtime friend Madison Smartt Bell, who has also just published Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone (Doubleday) and edited The Eye You See With (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), a selection of Stone’s nonfiction writing.

Bell is a professor of English at Goucher College and the author of fifteen novels, including his acclaimed trilogy on the Haitian Revolution, three collections of short stories, and five works of nonfiction. Via email, he responded to our questions about Robert Stone and his work just as much of the country was going into coronavirus lockdown.

Library of America: “I love America, so it enrages me—if I didn’t, I wouldn’t be so angry, nor would I make America my subject,” Robert Stone once told an interviewer. What do the three novels in this volume tell us about America, and particularly about the impact of the Vietnam War on American society and culture?

Madison Smartt Bell: It took a long time for the Vietnam experience to produce a war novel equivalent to Norman Mailer’s The Naked and Dead (or for such books to get very much attention). In the mid-1970s, before works like The Things They Carried and Going After Cacciato had begun to appear, Stone’s Dog Soldiers was considered by many to be the best Vietnam novel out there, and it was considered to be curious that so little of the novel was actually set in Vietnam. There is only one brief, remembered combat scene, though it is important.

The Vietnam War became a benchmark for America’s loss of innocence, not so much because of its intrinsic character but because of the reaction at home. The Korean War might have done the same thing but did not have much effect on the American social fabric of the early 1950s, in part because American veterans of the Korean War were close-mouthed about the trauma of their experience, as World War II veterans had been. Stone did his own military service in the late 1950s, in peacetime, as the American military apprenticed itself to its expanding role as the world’s policeman.

The Vietnam War blew all that up. World War II was seen as a just war; Vietnam the opposite. The American social fabric began to unravel, thanks to controversy over the war, alongside the often–violent struggles of the Civil Rights movement, and the surge of a young leftist counterculture. Complacency was no longer possible. The omnipresence of recreational drugs in the counterculture and in Vietnam lent the whole situation an air of decadence. The genius of Dog Soldiers is to set its drug-running picaresque on the home front, among characters who can no longer get any sort of moral compass from the culture disintegrating around them.

For many of Stone’s generation, the Vietnam period was the era of lost illusion, which is very powerfully felt by the protagonists of A Flag for Sunrise and Outerbridge Reach. In the former novel, Frank Holliwell’s cynicism, along with his recurring bouts of rage and despair, derive from his Vietnam experience—which he can sense in others, like a common wound. In its political dimension, Flag is really an early critique of the pernicious machinations of international corporations in the Third World, but the expectation of corruption derives from Vietnam.

The men of Outerbridge Reach are a bit younger than Holliwell; several of them emerged from the semi-chivalric culture of the U.S. Navy, then got their naïve idealism battered in (where else?) Vietnam. Owen Browne wanders toward middle age looking for a just battle he might fight—which at first presents as a kind of strength but ends up a fatal weakness.

LOA: Stone’s novels are tales of physical and moral extremity, often set outside the United States—Vietnam, Central America, the South Atlantic—or in a troubled psychological/cultural American locale—California after the Manson murders, New York City after the late ’80s market crash. What do you think it was about Stone’s own experiences, and the writers who influenced him, that drew him to write stories of extremity?

Bell: A simplistic answer would be that it’s difficult to derive a compelling story about things going uneventfully well in ordinary life—that’s been done but not often. Writers are therefore drawn to conflict, and Stone perceived that the life of his generation was in constant conflict of one kind or another.

There’s a deep-seated human belief that people in extremis reveal who they really are. Conrad novels like Lord Jim operate on that principle, and so do Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. But Stone’s attitude toward the experience comes as much from his own experience. While in the Navy he witnessed a battle during the Suez Crisis in Egypt, and on the spot thought:

I always knew this was the way things were. I always thought that the world was filled with evil spirits, that people’s minds teemed with depravity and craziness and weirdness and murderousness, that that basically was an implicit condition, an incurable condition of mankind. I suddenly knew what was meant when Luther said, “The world is in depravity.”

A little later, he drew a further conclusion:

I thought, “This is the way it is. There is no cure for this. There is only one thing you can do with this. You can transcend it. You can take it and you make it art.”

That, I believe, is his first enunciation of the idea he followed for all his working life.

LOA: About Outerbridge Reach Stone wrote: “Reading is a serious pleasure but a pleasure all the same. With this in mind I have tried to please, to tell a good story, without which I think no amount of high-minded intentions will avail.” Each of the novels in this volume tells a “good story” very well. Dog Soldiers has been compared to the crime fiction of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, A Flag for Sunrise to the political thrillers of Graham Greene and John le Carré, Outerbridge Reach to the classic sea stories of Melville and Conrad. Yet reading Stone is not like reading anyone else. What makes Stone a unique storyteller?

Bell: Sure, we’re all supposed to be entertainers at least in part; it goes back to the Middle Ages, when narratives were understood to instruct by pleasing. I think of Marlow, Conrad’s frame narrator for Heart of Darkness: Marlow is certainly telling a story of serious import but he’s also very intent on making sure it’s a good yarn.

Stone’s tone has something in common with Chandler’s, the atmospherics defined as “noir”—though as much as I do admire Chandler, I think Stone’s tone is richer and deeper, and his stories generally more significant. Stone is a lapidary realist in reporting on the world, but he’s also, perhaps primarily, a psychological realist, and his language is always situated deep within the inner lives of his characters. There’s the great difference between Stone and Hemingway. Both knew the importance of faithfully reproducing the action that inspires feeling, but Stone goes much further in exploring felt experience than Hemingway permitted himself to do.

As for his uniqueness, I think Stone, for all his elaborate procrastination, was finally willing to work harder than most writers are. To finish a text, he would work so hard it really hurt (which helps explain the procrastination, I think), and come out with prose that has the density of diamonds, and that repays rereading much more than other contemporary writing does.

LOA: Stone excels at creating and bringing to life characters, such as Danskin in Dog Soldiers and Pablo in A Flag for Sunrise, whom most of us would probably not like to meet in real life. What is it about Stone’s background, and his view of the world, that allows him to create such frighteningly real psychopaths?

Bell: He had known a fair number of people like that, as a street kid in New York and briefly in Chicago, and also in the Navy. In Dog Soldiers, Hicks gets called a psychopath by Converse, but really isn’t one. Danskin, a minor character, might qualify, but I think it’s better to use Stone’s term for a character like Pablo: an “institutional man” equipped with a set of semi-pathological behaviors acquired in orphanages, jails, and the military. But for the grace of whatever, Stone might have become such a person himself—he had a good number of the formative experiences for it—so he has insight into a character like Pablo, and considerable sympathy as well. For a more complex example, take Strickland in Outerbridge Reach. There’s a good deal of Stone in both characters.

LOA: In A Flag for Sunrise a woman asks Frank Holliwell, “Is there a place for God in all this?” Holliwell replies: “There’s always a place for God, señora. There is some question as to whether He’s in it.” In his novels fear, and often a terrifying sense of evil, are pervasive presences, while his characters struggle to find a sense of moral order in the universe. How important is the question of moral purpose in Stone’s fiction?

Bell: Holliwell’s line is a succinct expression of Stone’s particular agnosticism: an uncertainty about whether the Divine exists independently of the conditioning of religion and the human need and desire for it. Almost all his work addresses the question in some way. He was raised Catholic, by Marist priests at Saint Ann’s school, and once said that it’s no easier to stop being Catholic than to stop being black. But he doesn’t express dogmatic Catholicism in his work the way Flannery O’Connor or Graham Greene do. (Stone detested being compared to Greene because their similarities were utterly superficial.) Instead his fiction usually engages some version of this question: If one doesn’t have God, and one may not, how does one orient one’s moral compass? I don’t think Stone ever thought he had the answer to that, but I do think he believed that there was an answer.

LOA: You’ve just published Child of Light, the first biography of Stone, and were his friend for two decades. What did you learn in writing the book that surprised you, and did writing his biography change your view of him as a novelist?

Bell: The voice of a novelist creates a personality that may have little to do with the person’s real personality. When readers fall for that personality, bad things can happen. Nothing blameworthy there—writers are not obligated to reveal the truth of themselves in their work. Some do, some don’t. There are excellent writers (I think of Hemingway and Richard Ford) who tend to express a single personality similar to their own. Stone’s range of characterization is much more various than that. Yet I do come away from this project thinking that the man is more completely expressed in his work than in most cases—the thorns, the roses, the whole nine.

As for surprises, if I told you I’d have to . . . never mind.