For the inaugural edition of Library of America’s new LOA at Home e-newsletter, LOA President and Publisher Max Rudin offered these remarks on James Thurber. The entire article is also available as a streaming, downloadable audio file (.mp3 format) at SoundCloud.

Click here to sign up to receive the LOA e-newsletter.

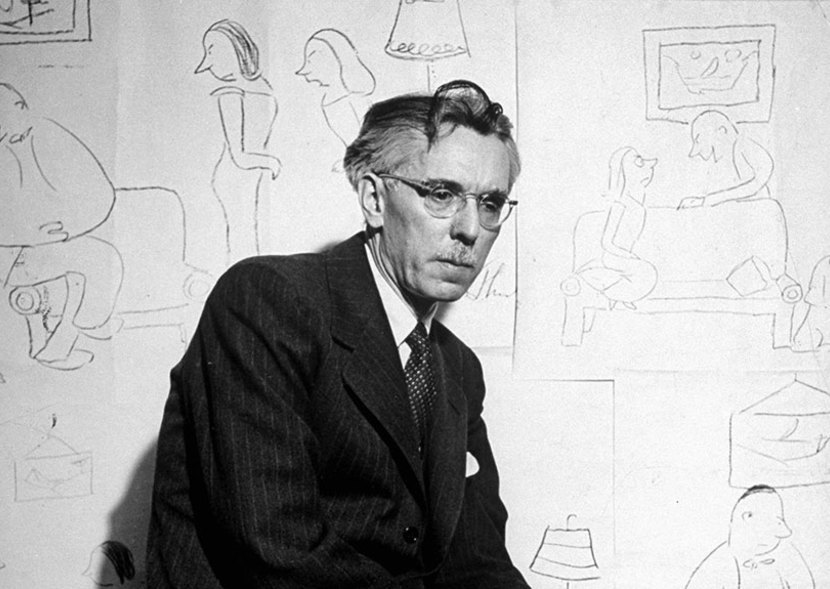

In 1926, James Thurber, still at thirty-three years old an aspiring writer, was living in a basement apartment on Horatio Street near the 9th Avenue El, and he was at the end of his rope. Broke, marriage failing, rejection slips piling up, he was marking time as a reporter before heading home, humiliated, to Columbus, Ohio and a career as a small time press agent.

Thurber had been born, raised, and educated in Columbus, and began his working life as a newspaperman there. But his ambitions had always been greater, and in the mid-Twenties he had followed Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and everyone else to France, where he quickly discovered he was not a novelist. It’s hard to imagine someone less cut out for the doomed, dissipated, self-dramatizing heroics of the Lost Generation. Tall, reedy, timid, and nervous, Thurber later said if he belonged to any generation it wasn’t so much Lost as Hiding. They celebrated tragic grace under pressure; Thurber had mastered, he said, the art of walking into himself. Fate, as a cruel joke, had handed him another reason for discouragement and self-doubt: in a childhood game of William Tell, his brother had shot a toy arrow into his left eye, which had to be removed, and infected his good eye as well. Even his tragedies had their ludicrous side.

Now, on Horatio Street, on the verge of giving up, some mysterious internal alchemy occurred. He began to write pieces that combined the ludicrous and the sad, the nervous rhythms of modern Manhattan with the matter-of-fact, casual deadpan of the midwestern editorialist. The first of these pieces, about a little man in a badly fitting overcoat who after a fight with his wife determinedly goes around and around in a department store’s revolving door, caught the attention of the editors of a sophisticated new humor magazine, founded the year before by Harold Ross. James Thurber was launched. He had not only landed himself a job at the New Yorker; he was inventing the first fully achieved style of American literary humor since Mark Twain.

Over the next fifteen years, through divorce and remarriage, worsening eye problems, bars, drunken cocktail parties, loneliness, depression, and nervous collapse, Thurber would somehow produce a series of remarkable volumes, including the classics Let Your Mind Alone, The Middle-Aged Man on the Flying Trapeze, Fables for Our Time, My World and Welcome to It, and his autobiographical masterpiece My Life and Hard Times. This, while creating the weekly Talk of the Town department with his friend and officemate E. B. White. And, incidentally, becoming a world-famous cartoonist.

| *ENTER THURBER’S WORLD* |

|

| James Thurber: Writings and Drawings |

Thurber, painstaking with his writing, was prodigal with his drawing. Impromptu murals covered the walls of the New Yorker and his two favorite bars, Costello’s on Third Avenue and Bleeck’s on West 40th Street. Compulsive doodles were everywhere in his and White’s tiny office—on the desks, on the floor, in wastebaskets. Finally White couldn’t stand it any more. He noticed a sketch of a seal on a rock looking at two far-off specks and saying, “Hm, explorers.” He took it, inked it, submitted it to the weekly art meeting—which promptly rejected it. The art editor drew a seal’s head on same piece of paper and sent it back to White with a note, “This is the way a seal’s whiskers go.” Ross asked Thurber: “How the hell did you get the idea you could draw?” Then, later that year, the book Is Sex Necessary appeared, copiously illustrated by Thurber. Published just after the stock market crash, it still sold 50,000 copies the first year, and the drawings were singled out for acclaim. Ross walked into the now famous illustrator’s office and asked for the “goddam seal drawing.” Thurber redrew it, but the rock came out looking like a bed’s headboard, so he changed the caption. His cartoons started appearing regularly in the New Yorker, and the other artists were incensed. One stormed into Ross’s office. “Why do you reject drawings of mine and print stuff by that fifth-rate artist Thurber?” he demanded. Ross looked at him. “Third rate,” he said. Thurber contributed 307 captioned cartoons until encroaching blindness ended his drawing in the early 1940s.

After the war, Thurber’s career entered a new phase. In 1945 The Thurber Carnival, a best-of anthology, became a Book of the Month Club main selection and a best seller. It sold half a million copies, and suddenly James Thurber was a household name. There had been Walter Mitty clubs in the Pacific and Atlantic war theaters, and “ta-pocketa-pocketa” had been a password on the front lines, but this was something different. Time put him on the cover and Saturday Review called Carnival “one of the absolutely essential books of our time.” Thurber endorsed Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American language, turned down Bostonian shoes and Old Angus Scotch. Danny Kaye starred in a movie based on “Mitty.” Enamel tea trays, textile prints, and coasters appeared using his drawings as motifs, and so did ads for Aqua Velva after-shave, Bug-a-boo insecticide, and the Franklin Simon department store. He wrote his lawyer: “One of your colleagues phoned me to announce ‘I have got your tax for this year down to $64,000.’ The idea that anything could be got down to a point that high distorted my thinking for several years, and when a movie producer wired me an offer of $300 a week, I wired back ‘Ross has met the decrease.’”

Dividing his time between West Cornwall, Connecticut and his favorite hotel, the Algonquin, he continued on occasion to write wonderful pieces, but his best work was behind him. Blind and dependent on others, beset with medical problems, he drank heavily, and his fits of irascibility and abusive rage alienated friends and family. His behavior may have been due to an undiagnosed brain tumor which doctors discovered just before his death in 1961. He left behind more than thirty volumes, many of which have never gone out of print.

In 1938, Thurber wrote to White: “There is nothing else in all the countries of the world like New York City life. It does more to people, it socks them harder, than life in Paris, London, or Rome, possibly could. God knows it got me. I don’t think this is due to weakness, any more than having your leg carries away by a shell is due to weakness. New York is nothing but a peaceable Verdun, with music and theatre.” Thurber was born the same year as Dashiell Hammett, and within five years of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Raymond Chandler, and T. S. Eliot. What World War One was for them, New York in the Twenties and Thirties was for him—the defining experience that made it necessary to invent a new literary style. Well into the twentieth century, American humor was dominated by Mark Twain and his frontier influences: exuberant, colorful, bursting with life, energy and incident, the humor of America’s Age of Expansion. Then came Thurber’s little man in a suit, eyebrows arched in perpetual alarm, placed in a constant state of discouragement, emotional confusion, and dread by the city, his marriage, his envy and hate of modern machinery, driven to take refuge in fantasy and mania—and American humor suddenly found itself in the Age of Anxiety.

In Thurber’s world everyone, except the dog, is a nervous wreck, and nothing really happens—the bed doesn’t fall, no ghost gets in. Or rather, and this is the essence of his modernness, the things that happen are inside people’s heads. Like this: “I had been trying all afternoon, in vain, to think of the name Perth Amboy. It seems now like a very simple name to recall and yet on the day in question I thought of every other town in the country, as well as such words and names and phrases as terra cotta, Walla-Walla, bill of lading, vice versa, hoity-toity, Pall Mall, Bodley Head, Schumann-Heink, etc without even coming close to Perth Amboy. I suppose terra cotta was the closest I came, although it was not very close.”

In the preface to My Life and Hard Times, which Russell Baker insists is the shortest and most elegant autobiography ever written, Thurber wrote this credo, a kind of epigraph to his best work and much American humor after him: “Your short-piece writer’s time is not Walter Lippmann’s time, or Professor Einstein’s time. It is his own personal time, circumscribed by the short boundaries of his pain and his embarrassment, in which what happens to his digestion, the rear axle of his car, and the confused flow of his relationships with six or eight persons and two or three buildings is of greater importance than what goes on in the nation or in the universe. He knows vaguely that the nation is not much good any more; he has read that the crust of the earth is shrinking alarmingly and that the universe is growing steadily colder, but he does not believe that any of the three is in half as bad shape as he is.”

Welcome to an American humorist for our times. Welcome to James Thurber.

Max Rudin, President & Publisher

Library of America