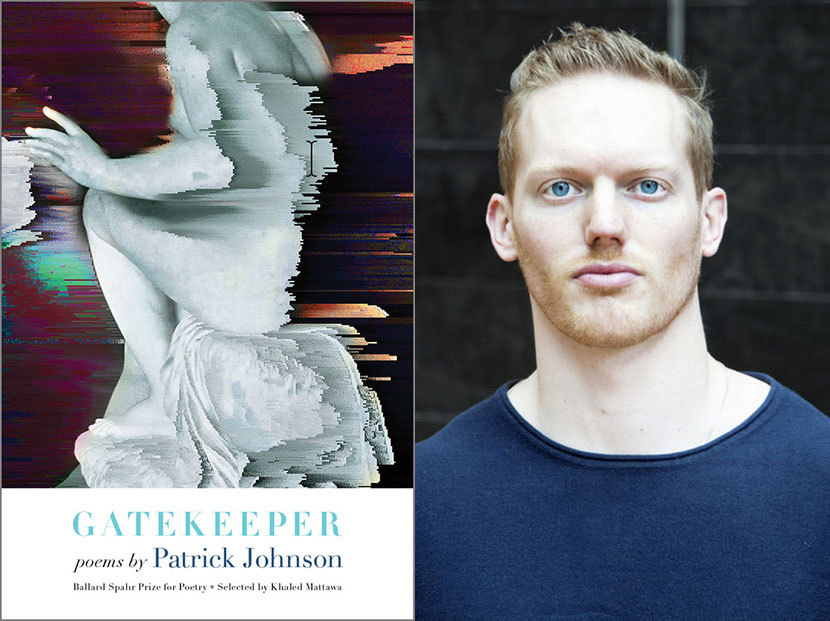

Our series of guest blog posts by contemporary American writers continues today with a contribution from poet Patrick Johnson, whose debut collection Gatekeeper was published late last year by Milkweed Editions.

In Gatekeeper, winner of the 2019 Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry, an unnamed narrator delves further and further into the “deep web” in an increasingly vertiginous and fragmentary journey. The book’s concerns seem especially pertinent in Spring 2020 given the new ways in which people are connecting (and tiring of connecting) via the internet. Johnson’s rendering of a uniquely contemporary kind of unease has been called “mesmerizing” by Mary Jo Bang and “successfully jarring and disturbing” by The Millions.

In the following piece, Johnson relates how the writers C. D. Wright, Jorie Graham, and Toni Morrison each had a role in helping to inspire both the form and the content of his debut.

In 2014 I gave a self-seriously awkward introduction to the late C. D. Wright, who was the visiting professor at Washington University in St. Louis in the last year of my MFA. To prepare for her visit, I read everything she had written at the library, so when it was time for our one-on-one meeting to talk about my poems, I wanted whatever she said to be a big deal: either she had read and loved them, or she’d interrogate me about all the poor choices I had made, pruning them back to something I could foster.

She trusted my poetic curiosity and the form my inquiry took—of course, our meeting wasn’t about positives or negatives. I had started wondering how my poetry would/should confront the world around me in a way that felt artistic but meaningful on a political level. Living in St. Louis at the time, my first and only time living in a majority-black city, after Mike Brown had been murdered in Ferguson just north, I studied poetry to hold a mirror to the changes I wanted to make in myself.

Maybe the most self-serious part of my introduction came when I looked up from my notes to pose the question to the audience, about C. D.’s work, “What happens when we see something we might distinguish as ‘the political’? What happens when we see it, feelingly?”

In “Rising, Falling, Hovering,” she writes:

Then: on a certain night and no other

Another telegenic war begins.

Can you describe this.

I cannot. This is not the day or the hour.

The color is all wrong.

What I admire is how she sets the stage for a reading experience where images operate in the reader’s mind without their words being overly adorned with devices, how the language can appear at once colloquial and beautiful, and how that tension can kind of politicize the mundane. Like, which “telegenic war”? The stakes become so high.

Another writer whose work has influenced me in the same vein is Jorie Graham. In “Reading Plato,” she writes:

Past death, past sight,

this is

his good idea, what drives

the silly daystogether. . .

It’s as if the poem presents images but also maps cognition—it renders ideas in a physical plane as objects that we can move past, like a book on a shelf or a rift in the earth—while also somehow describing the process of writing/reading. The poem becomes a system or a philosophy.

I became interested in systems because I realized I identify as bisexual. A lot of my interest in writing came from my interest in theories—things about the world that weren’t accepted as true, but could be. I love how Judith Butler writes in Gender Trouble about how gender is basically fake and then later in another book writes that the way we think about biological sex is bogus. Or Michael Warner and Lauren Berlant’s essay “Sex in Public,” which discusses how the social pressure of taboo around sex estranges everyone from desire.

I’ve always been interested in artists and writers whose work has taken on big, progressive projects. I remember reading Toni Morrison in high school and learning that her storytelling is about her characters but also about the racialized minds of her readers. In Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, she asks:

What does positing one’s writerly self, in the wholly racialized society that is the United States, as unraced and all others as raced entail? What happens to the writerly imagination of a black author who is at some level always conscious of representing one’s own race to, or in spite of, a race of readers that understands itself to be “universal” or race-free?

Gatekeeper started as poems in terza rima about the internet and became a book of lyric poems and short essays, with instant messenger chat logs, an internet love story. . . . With this book I wanted to make C. D. Wright’s “telegenic war” an internet war, to descend into its inferno and imagine what could be.

Patrick Johnson earned his MFA in poetry at Washington University in St. Louis and completed his undergraduate degree in English Literature with a certificate in Material Culture Studies at University of Wisconsin–Madison. He currently lives in Madison, where he is studying to become a physician assistant.