In 1895, Mark Twain embarked on an extraordinary lecture tour around the world, during which he also visited historical sites, observed customs, and—as you might expect from him—published his encounters and opinions in a travelogue, Following the Equator. Recently, one eminent Twain scholar set out on her own expedition modeled on Twain’s itinerary, and earlier this month she published a book about her discoveries.

Susan K. Harris’s Mark Twain, the World, and Me is no ordinary study of a great American writer. It examines our current world as much as it explores Twain’s own nineteenth-century backgrounds. It investigates contemporary cultures in South Africa, India, and Australia and, in doing so, offers perceptive analyses of American life today. It follows Twain’s own cues to grapple with topics that most readers wouldn’t ordinarily associate with this writer: animal preservation and gender crossing, religion and colonialism, environmental pollution and race. And along the way, it takes the reader on an intriguing and insightful journey across centuries, cultures, and continents.

Susan K. Harris is Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of Kansas. She is the author of God’s Arbiters, which focuses on Twain’s opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines in 1899; The Courtship of Olivia Langdon and Mark Twain; and Mark Twain’s Escape from Time. Additionally she has coedited the New Riverside Edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and edited LOA’s own collection of Twain’s three historical romances. Harris currently lives in Brooklyn, New York, and took the time to answer some questions for us via email.

Library of America: What inspired you to follow Twain’s journey around the world? Wouldn’t it have been easier to do all your research online or in U.S. archives?

Susan K. Harris: In literary scholarship, one book tends to lead into another. I became interested in Twain’s journey around the world because I had just completed a book (God’s Arbiters) about his opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines in 1899, and I wanted to know why he became an anti-imperialist. He hadn’t always felt that way. When the U.S. first proposed annexing the archipelago he was all for it. “I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific,” he remembered in 1900. “I said to myself, here are a people who have suffered for three centuries. We can make them as free as ourselves, . . . put a miniature of the American constitution afloat in the Pacific, start a brand new republic. . . . It seemed to me a great task to which we had addressed ourselves.” But by 1900 he had changed his mind. Now, he told reporters, he understood that “we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . . . And so, I am an anti-imperialist.”

So, my question to myself was: Why? What had he learned about colonial possession that converted him from imperialist to anti-imperialist? His thirteen-month lecture tour around the world lay between his embrace and his rejection of American expansionism, and I thought that the trip itself had to be the catalyst for change. Perhaps observing the workings of British colonialism in countries like India and South Africa had shown him its perils. I found a few clues in Following the Equator, the book he wrote about the tour, but not enough to go on. I visited the archives, especially UC Berkeley’s superb Mark Twain Project, but the diaries and letters I found there just weren’t giving me the information I needed. So I thought that maybe I could hit pay dirt if I went to the places Twain visited, looked into local archives, read through other peoples’ reports about his sojourns among them. And that launched my own journeys.

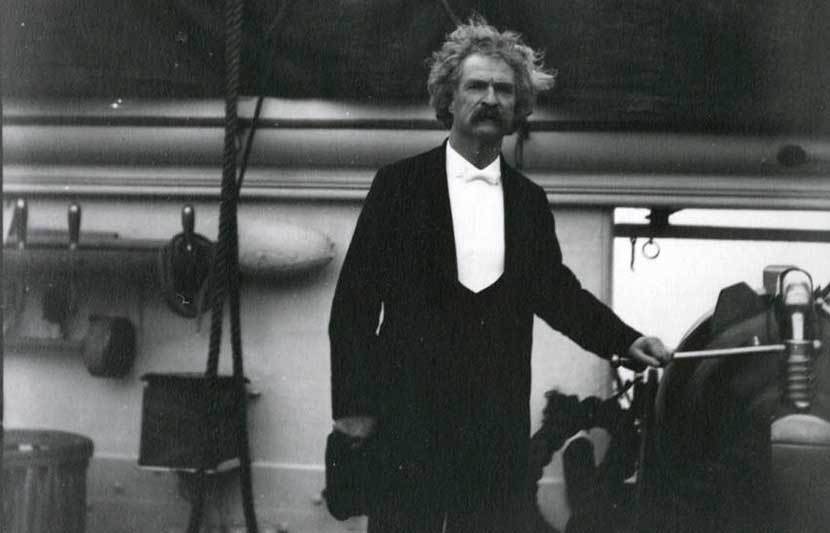

The result? I never figured out exactly why Twain changed his mind about the U.S. becoming an imperial power. There was never an “aha!” moment. But that doesn’t mean my journeys were unproductive. On the contrary: pursuing Twain as he traipsed through the British Empire showed me how he interpreted his new environments through both his own background and his deep interest in storytelling. Twain visited Fiji, Australia, New Zealand, India, Mauritius, and South Africa on his tour, and he commented on all of them through the lenses of his own longstanding concerns: his interests in race and racial mixing for instance, as well as in animals and their relationships with humans, in religion and its practices, and in settler histories.

I’ve lived with Twain for over thirty years, and I never cease being amazed by the breadth of his interests, his curiosity, and his prescience about the future. Most importantly, by following his commentary about what he saw on his journey, I began to see some of the continuities between his time and ours. And that led to a very different type of book than I thought I was going to write.

LOA: In your book, you say that Twain “never stands still” and is an “authorial shape-shifter.” What do you mean by that, and how did your journey affect your understanding of him as a writer?

Harris: Anyone who has tried to work closely with Twain’s writings knows this frustration. You think you have a firm grasp on what he thinks, only to have him flip to the other side. For instance, pretty much the whole section of Following the Equator that deals with Hinduism, especially as evidenced in Benares, the Hindu holy city (now Varanasi), treats the religion as irrational and its adherents as carriers of deadly diseases—the latter a trigger point for Westerners, who were still coming to grips with the recently-discovered germ theory. One of Twain’s chapters satirizes the pilgrimage circuit around Benares. His deft caricature, which emphasizes the link between religious practice and disease, was probably very funny to white westerners in 1897 but was richly insulting to Hindus then and now. One of the British Empire’s strategies for undermining Hindu legitimacy was to broadcast this link between religion and disease, and reading Twain’s satire through the history of those narratives shows Twain playing to his British hosts. So you think, “OK, this guy is not interested in actually trying to understand Hinduism.”

But—whoops!—a few chapters later he records his meeting with Swami Bhaskaranand Saraswati, a Hindu holy man whom he respected. So he ends the Benares section, the majority of which has trashed Hinduism, with a lecture to his readers about tolerance: “the respect you pay, without compulsion, to the political or religious attitude of a man whose beliefs are not yours.” And my response is, “Are you kidding? Have you read your previous three chapters?” And of course the bigger question is, “Which Twain is the real Twain?” Got me. You just don’t know where he’s going to land—and when he does, if he’ll stay there.

LOA: You reflect a lot on Twain, American culture, and yourself throughout Mark Twain, the World, and Me. What were some of your most important discoveries during your odysseys in distant countries?

Harris: You’re right; not only did I learn a lot about Twain and about American culture during my odysseys (great word!) but I also learned a lot about myself. At some point in my first few months of writing, I decided to put myself into the book, as a character and first-person narrator. I’ve never done that before, and learning to write about myself was an adventure in itself. The title, Mark Twain, the World, and Me, describes the triangulation I ended up with: Twain’s life and thought, my life and thought, and the world that both contextualizes and connects us. We are both Americans, and we think like Americans, but we come from disparate strata of American life, which means that we approach new experiences very differently—across time, gender, religion, education, and prior travel, for starters.

For instance, coming from a Jewish background, where many of the prayers and rituals are rooted in Middle Eastern forms, I don’t feel as alienated by Hindu rituals as Twain did. And as a white woman married to an African American man, with a bi-racial daughter, my sense of my family’s racial standing in South Africa is vastly different from the Clemens family’s confidence that they stood at the top of the racial pecking order. Comparing our responses to the complexities of South Africa’s racial orders—in 1896 and in 2014—sharpened my understanding of both our social positionings.

Yet even as I compared and contrasted Twain’s adventures and my own, I also learned a lot about the American culture we share. Twain gives a whole chapter to the subjugation of Tasmanian Aborigines in Following the Equator, and probing into his sources opened up a huge historical scenario that I had known very little about. The project of moving indigenous peoples into reservations and sticking their children into boarding school hundreds of miles from home, for instance. I was familiar with the process here, but until I went to Australia I just didn’t realize that U.S. policy towards its indigenous people had been modeled on an agenda that was being implemented across, at least, the entire Anglo-Saxon colonial world.

The same goes for the legacies of those policies a century later. I’d lived through the Civil Rights movement in the U.S., but until I saw 1960s photographs of Australian Aborigine “freedom buses” and South African school boycotts I didn’t realize how influential our own fights for racial equality had been. So my odysseys taught me a lot about nineteenth-century U.S. participation in a global campaign to subjugate, even eliminate, native peoples, and about the equally global kickback by those peoples in the twentieth century.

LOA: What is it that makes Twain’s writing such an enduring part of American culture?

Harris: His fantastically fluid and inventive language, his sense of humor, his insights, his deft satires. And his curiosity. And his prescience. Samuel Clemens had all the prejudices of his time and place, but he also had a keen grasp of the subjectivity of class and racial difference, a visceral hatred of human cruelty, a furious appreciation for human stupidity, and an extraordinary sense of the repetition of human scenarios over time. As I write this I’ve recently come home from two weeks in Peru, where I had no internet connection. When I left New York, all was routine; when I returned, Covid-19 had turned the world upside down. And I keep thinking about the end of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. After spending years modernizing sixth-century England, Hank Morgan, the narrator, goes on a cruise with his wife and child. They leave a land of bustling commerce, electric lights, universal education. They return to darkness: empty streets, frightened people, “a desolate silence everywhere.” During Hank’s absence the medieval Church, Hank’s archenemy, had imposed the Inderdict, making clear its determination to “snuff out my beautiful civilization just like that.” The scene keeps returning to me as I forage for food among Brooklyn’s stripped shops and silent streets. Twain understood the circularity of time and human idiocy. That’s why his works come back to haunt us.

|

| Mark Twain: Historical Romances (edited by Susan K. Harris) |

LOA: Do you have any recommended readings for those who may only be familiar with Twain’s most famous works (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn)?

Harris: For novels: A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and The Gilded Age (the latter co-written with Charles Dudley Warner). And of course Pudd’nhead Wilson, which is all about race and gender mixing. And for Joan of Arc fans, Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, by the Sieur Louis de Conte. It’s a historical novel about Joan of Arc. Some people love it; others think it’s awful. Readers’ choice!

Travelogues: Twain was as famous for his travelogues as for his fiction: try The Innocents Abroad, for starters, then Roughing It or Life on the Mississippi, and finally Following the Equator.

Short pieces: you can’t do better than LOA’s own Mark Twain: Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays, Volumes I (1852-1890) and II (1891-1910).