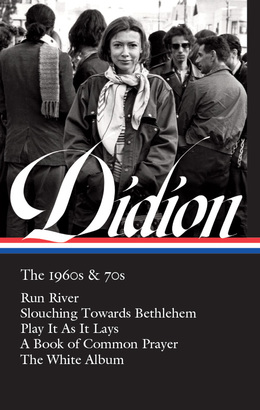

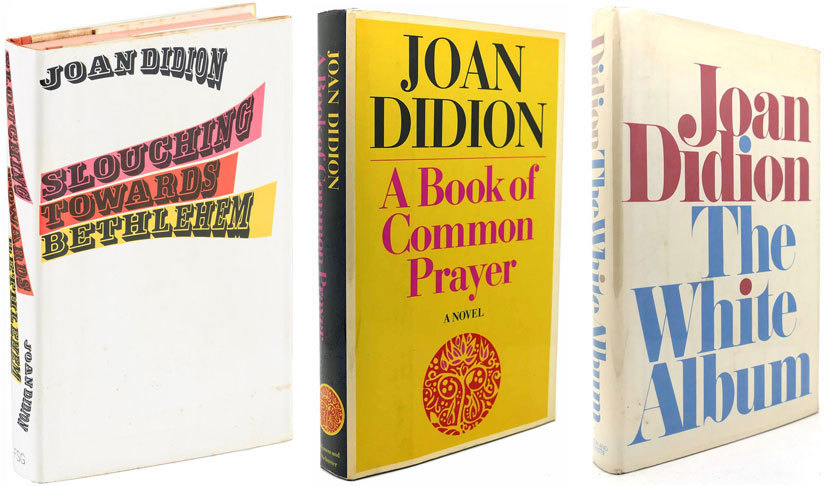

One of the most singular voices in contemporary American letters enters the Library of America series with the arrival of Joan Didion: The 1960s & 70s, a blockbuster compilation that collects the novels Run, River (1963); Play It As It Lays (1970); and A Book of Common Prayer (1977), along with the two books of Didion’s nonfiction that can rightly be called seminal: Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979).

The book is edited by David L. Ulin, former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the author or editor of ten books, including Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, Labyrinth, and The Lost Art of Reading: Books and Resistance in a Troubled Time; he also edited Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology for Library of America.

Via email, Ulin shared with us some thoughts on why Didion has been transformative on his own career as a writer and why her work continues to resonate so strongly today.

Library of America: “Didion is the reason I became an essayist,” you recently acknowledged; we suspect you’re not alone in feeling that way. Can you describe some of what it is about the essays in Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album that first electrified you, and still holds you today?

David L. Ulin: First and foremost, it was the voice. I had never quite encountered anything like it before—that balance of distance and engagement, the sharp eye of the observer, the notion of looking at everything (a little bit, at least) from the outside. Also, the interplay of personal and reported material, the way Didion was writing about both her own life—or her own perspective—and the moment in which she lived. I was looking (although I didn’t know it yet) for a way to do something similar, to produce literature that also spoke to and out of its own moment, that acted as a kind of commentary. Personal narratives connected to something bigger, in which the narrator is the lens through which the story operates, if not always the protagonist. All of this spoke to me deeply, as a form of story-making that made sense.

Also, there was the open-endedness of much of the material, the notion that the narratives were never finished because they were still what she was living through. All of this was transformative to me as a young writer. It was like being given permission, a kind of permission I’d never realized I could have.

LOA: One of the marvels of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion’s first nonfiction book, is that it marks the arrival of a fully formed, utterly distinctive prose style. What kind of apprenticeship accounts for such a striking collection? Or, to put it another way: Where did that voice come from?

Ulin: I don’t know that any apprenticeship accounts for the collection. Or to put it more accurately, perhaps the apprenticeship was her life. We know that she read and typed out Hemingway when she was younger, and certainly, there is an affinity between their styles.

But I think what we’re seeing in Slouching is a writer responding to her moment—not just in terms of content but also in terms of structure and style. The fragmentary movement of the title essay, for instance: It’s brilliant, but not as an abstraction; rather, it has to do with how it evokes the fragmentary nature of what she describes. So, too, “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” which is at heart a magazine feature about a murder trial, but then we see what she does with that, how she builds the piece to be about so much more.

Didion is looking for signifiers, she’s looking for the bigger connections, the bigger narratives. And yet, she already understands that these will not sustain us, and this tension operates throughout the book. This is the key to her voice, her style, I think—her desire to believe or belong, on the one hand, and her clear-eyed understanding, on the other, that this can only be a temporary solace, if it is solace at all. As it happens, I share that point-of-view, which is one of the key reasons her work resonates. I think it is the genesis of her style.

LOA: Stylistically there’s a huge leap between Didion’s first novel, Run River (1963), and her second, 1970’s Play It As It Lays. Run River still has one foot in the tradition of midcentury realism whereas the spare, fragmentary Play It As It Lays practically reads like a New Wave movie for the printed page. What do we know about this stylistic evolution—was there a series of false starts before she got what she wanted in Play It As It Lays, for instance?

Ulin: My sense is that it’s an aesthetic progression, keyed in some sense by what she was doing in the essays. Run River, after all, is a book by a different writer, from a different time. It is essentially looking backward at the world from which Didion has come—which is often the territory a first novelist occupies—whereas Play It As It Lays is looking out at the world in which she now lives. That world is Hollywood, and it is also the unmoored landscape of the late 1960s and early 1970s, with its collapsed or broken narratives.

I read the style of Play It as one more iteration in her ongoing interrogation of narrative. She is continuing the works of essays like “Slouching” in eclipsing the connective fiber between moments—which, of course, is a reflection of what she’s seeing in the larger world.

LOA: Assessing Didion’s career in the London Review of Books last year, Patricia Lockwood argued that “To revisit Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album . . . is to read an old up-to-the-minute relevance renewed.” Is the “dread” you have identified as a running theme in these books part of what makes them feel current, or renewed, forty and fifty years after they were published?

Ulin: I think a few things make them feel current. One is that sense of dread, which is really existential, and as such timeless (although consumed with time). Another is that we are living in a similar moment of narrative breakdown and atomization . . . or perhaps, it’s most accurate to say that such a moment never ended, that the lack of through line has, paradoxically, become the through line for American life. Didion is drawn to disruption: social, cultural, personal. This is the way we all now live. In that sense, what she’s identifying in those essays are what we all see around us. It is all part of a continuum.

LOA: In retrospect Didion’s novel A Book of Common Prayer (1977), set in the fictional country of Boca Grande, can be seen to inaugurate a period in which several leading American writers took on Latin America’s relationship to the United States as their subject. (We’re thinking of not only Didion’s own later nonfiction titles Salvador and Miami, but also novels by Robert Stone and Denis Johnson and some of Deborah Eisenberg’s short stories, for instance.) What led Didion, who made her reputation as a chronicler of the American scene, to direct her gaze south of the border?

Ulin: She made a trip to Bogota (there is an essay about it in The White Album), and that experience opened up the territory to her narratively. But I also have to think this is a natural progression for her, both as an American (given the political and foreign policy culture of that moment) and, more importantly, as a Californian. Living in California, it’s impossible not to define “America” in broader, more inclusive, terms that extend beyond the borders of the United States. I think Didion’s interest grew out of her understanding of these connections, both in terms of California and the national conversation as a whole.

Read David L. Ulin’s essay “Didion, Revisited” on barnesandnoble.com