Library of America notes with sorrow the passing of literary critic and scholar Harold Bloom, who died in New Haven, Connecticut, on Monday at the age of 89.

A member of the Yale University English Department since 1955 and the author of more than forty books, Bloom was best known for his 1973 study The Anxiety of Influence and Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, which became an unexpected best-seller on its publication in 1998.

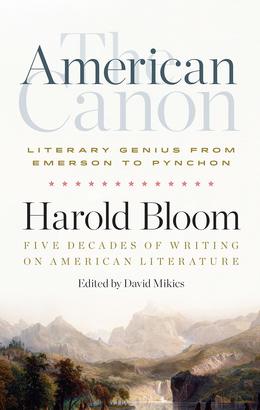

Bloom died one day before LOA released his latest book, The American Canon: Literary Genius from Emerson to Pynchon, a collection of essays edited by David Mikics that examines the ways in which classic American writers have influenced one another over the past two hundred years.

The American Canon is only the latest chapter in Bloom’s longstanding relationship with Library of America. He edited the anthology American Religious Poems and Walt Whitman: Selected Poems, and he co-edited (with Paul Kane) Ralph Waldo Emerson: Collected Poems and Translations. He also introduced the LOA Paperback Classic edition of Nathanael Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.

“Harold Bloom was the surest, deepest, most intuitive reader of literature I’ve ever known,” said Library of America President and Publisher Max Rudin. “Great imaginative works were for him sacred texts, to be grappled with and returned to again and again throughout one’s life in a spirit of discovery and transformative self-discovery. He was willing to write extravagantly about them—in the mode he called (I could never tell whether with a wink or not) ‘the Critical Sublime’—as a way to convey his passion and reverence, his conviction that issues of utmost consequence were at stake. He was a great and noble person, also warm and tender and funny, with an enormous gift for loyal friendship. He was one of Library of America’s greatest friends and advisors from the beginning, and we will miss him.”

Library of America Editorial Director John Kulka commented:

“Harold Bloom will always be associated with the ‘anxiety of influence’ in explaining how the creative process works, and with a few popular books that came later in his career. But whenever I talk to someone familiar with his work beyond The Anxiety of Influence and a few best-selling titles, what they tend to value in his writing are the many wonderful critical observations, especially those about poetry, which was always more important to Bloom than prose, his great love for Dickens, Faulkner, and other novelists notwithstanding. The work on the British Romantics remains first rate—along with his writing on the sublime American poets who mattered most to him—Whitman, Dickinson, Stevens, and Hart Crane. Later in life he came to a real appreciation for the poetry of Ursula K. Le Guin and enjoyed a friendship with her via email.

“The house on Linden Street in New Haven was like Dr. Johnson’s lexicographical laboratory, books and papers strewn about, and full of life and activity that moved around the great man. Harold Bloom lived and breathed literature, more so than anyone I’ve known, and was always willing to share his views on any writer. But I think the real work was done in the small, lonely hours of the night, when the voices of the dead spoke most clearly to him. I was fortunate to have worked with David Mikics in editing Bloom’s most recent book, The American Canon, which collects five decades of his writing on American literature. . . . I take consolation in knowing that he saw the finished book before his death.”

Several writers, many of whom knew Bloom personally, shared tributes with LOA on the news of his passing.

David Bromwich, Sterling Professor of English, Yale University:

Harold Bloom was a profound interpreter of poetry, a gifted and enthralling classroom teacher, as original-minded as a scholar can be. His judgments were delivered with a plainness and candor which his precision of phrase could often make unforgettable. He had a way of asking a question that stayed and sank in.

John Burt, Professor of English, Brandeis University:

Nobody had as much to do with my intellectual life as Harold Bloom. I took his class just to fulfill a distribution requirement in 1975, and then had many of the science-major prejudices about the humanities—that nothing in it counts as knowledge, that all its methods are flabby, that it is tyrannized by feeling and opinion. Bloom’s course opened my eyes to the way thought and feeling can illuminate each other, and to the ways that poetry can help us face but not to solve some of the deepest questions of human living, our purpose in living in the world, our ways of being with each other, the ways we face death, the ways we face our own moral weaknesses and moral dark side. He gave me an ear for the implicit and inexhaustible aspects of poetry and language. He opened for me all of the depth and richness of the humanities, and showed me what a nuanced, morally deep, and emotionally rich experience of reading is. I can’t measure my gratitude for his teaching and example in words. I can’t express how sad his death makes me.

Novelist Joshua Cohen:

Bloom has been lauded for many things—including his mastery of the list—but among the muchness of that list (wisdom, intellect, industry, etc.), it’s his heart that deserves a funereal mention. If you’d ask the generations of critics who fluenced from Bloom why the head took precedence over the heart in the usual roll-call of his virtues, I’d guess that they’d answer that his head was overwhelming. And while that’s true—it was overwhelming—there’s still a truer answer and it’s that his heart was terrifying. His passion was terrifying. More so than his memory, more so than his taste, at least by my lights. I was and remain utterly terrified by the urgency and, especially, by the gravity of Bloom’s passion, which made a mission out of literature and could only turn the professionals and clock-punchers, the snobs and social-readers, into enemies . . . often against their will and better judgment. (Of course, Bloom had the intelligence and luck to have taught generations of his enemies that they were his enemies . . . and yet, has even one of them even bothered to say thank you?!)

Bloom waited for The Book like Jews must wait for the messiah, not passively or skeptically, but actively, even wildly, patrolling the city walls and posting up at the city gates to examine all who pass—to examine those coming in and those going out, the merchants and the beggars equally. This was Bloom’s joy and his joyous duty. Blessed be he who takes curiosity for a commandment.

Peter Cole, poet, and Adina Hoffman, essayist and biographer:

You wouldn’t know it from the media coverage after his death, but there were many Harolds—and, like his Walt, he contained multitudes. There was Harold the Notorious and Harold the Genius, Harold the Terrible and Harold the Oracle, and we knew them all well. Sometimes too well. The Harold who mattered most to us, though, was Harold the Insatiable—a man whose hunger for poetry was matched only by his appetite for engaged human company, and always, on the page and in person, for “more life,” which was, as he put it again and again, till the very end, “The Blessing.”

Conversations around his and Jeanne’s plain and pot-marked dining room table were testament to that appetite, that vitality, that blessing.

His hungers could also be quite literal: he loved to eat hearty, unfussed-over food, and he was a voracious delight to cook for—precise in his cravings, emphatic in his pleasure (“Adina, your matzo balls are shocking!”). Even in his later frailty, he would make very specific, slightly eccentric culinary requests which it was almost impossible to deny him. Passing an encrypted, or at least cryptic, message through a mutual friend who’d been visiting him one afternoon to talk about John Ashbery, he told her (mysteriously) to tell us: “Persian”—knowing we would understand that this meant he’d like us to join forces with Jeanne and whip up a kuku and a khoresh, with some crisp-crusted rice, which the four of us would devour around that almost always book-heaped dining room table.

The first time we shared a meal around this somehow magical piece of furniture, we scrambled to clear the books off and make room for the plates and glasses and food. “Just leave them, Kinderlach,” he gestured with his eyes, using his childhood Yiddish to call us “children.” “No need to stand on ceremony” . . . as the meals morphed into one another, from the page to the plate and then back to the page, and on into the Yankees game (there was also that Harold—the front-running fan from 1410 Grand Concourse, in the Bronx) . . . or a DVD of F. Murray Abraham doing Shylock.

And then there were the Passover seders that, for some ten years, we held in the same dining room. Here, too, Harold always wanted to surprise the texture of the tradition, and he’d gently insist that, each time, we concoct a different angle onto the out-of-Egypt story. Make it new, as the rabbis urged, and as, in a very different context, did Ezra Pound, whom Harold loathed, and whom we love. The particulars were up to us, but the basic idea was to keep Harold engaged till dinner was served. So it was that we celebrated together each spring, in generally gleeful, and often heretical, fashion: an American Songbook seder; a Bundist seder; a kabbalistic seder (“Peter, what are we reading? You really need to write this one up!”); a seder we described loosely as Shabbatean (i.e., Judeo-Islamic-Scholemanian-antinomian); and a seder that included Exodus poems by George Oppen, Leonard Cohen, the contemporary Israeli poet Aharon Shabtai, a modern translator’s rendering of an Old English version of the Parting of the Sea, and the now almost wholly forgotten but once best-selling bard of Hart Crane’s late 1920’s, Samuel Hoffenstein:

After the trouble and the tears,

After the wraths and the wraiths depart,

Peace, nurtured by the lonely years,

Blooms like a cactus in the heart

and pierces all. . .

Usually, ritually, Harold got a kick out of reading the part of the Wicked Son. With a wicked smile. This last year, by chance, he was the Wise one.

And so he remains.

Novelist William Giraldi:

For those of us who called him mentor, the loss of Harold Bloom means an enormous vacancy that cannot be refilled. His embrace of me as a critic, combined with his warmth to me as a writer, is the one great validation of my working life. His kindness to my family—he called our three small boys his “little bears”—even as his body insisted on failing him, was an uncommon force of generosity. The loss of him means also the loss of the last influencing titan of literary excellence and the poetic sublime, the apostle of aesthetic criticism who taught that knowing ourselves and others to the fullest is contingent upon literary love, a life of dynamic engagement with the best that’s been written. . . . When I last saw him, not far from the end, at his home in New Haven, he recited to me staves from Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” a poem that contains the line “Though much is taken, much abides.” Much indeed has been taken, but what abides are the three shelves of books Bloom authored; this monument he has left us is adamantine, impervious to trend.

(Giraldi conducted one of the last substantive interviews with Bloom for the Los Angeles Review of Books earlier this year.)

Langdon Hammer, Niel Gray, Jr. Professor of English at Yale University:

In 1979 I was a senior Yale English Major living a mile or less from campus. Out on the sunny bland avenue, I watched Harold Bloom punctually on Tuesdays walk to teach his class. His feet slid along rather than took steps. His shoulders tilted back, his eyes were closed, and his mouth was moving, without sound. The effect was of a sort of ship. He seemed at once in the world—there he was on foot, predictable as a ship on schedule—and yet also somewhere high and far away, like Wordsworth wandering lonely, or the Unbeliever asleep on top of a mast.

As a PhD student, I took his seminars on Romantic Poetry, Freud, and Contemporary American Poetry. He made the classroom a place of the greatest seriousness and intensity, although that makes it sound more solemn than it was. He was of course completely in charge. But he wasn’t lecturing. Rather, he was asking questions, and very often the same question over and over, as the rest of us tried to answer it. Sometimes that meant Harold asking us to identify the source echoed in some line. Then, comically, hands would go up and students would tentatively name Bloomian favorites—Shelley, Emerson, Nietzsche?—hoping one would be right. But more often what he was doing was something real and profound that I experienced in no other classroom. He was inviting us into his own reading of a text, which involved interrogating it, musing on it, and simply staying with it longer, and applying more pressure to it (and to ourselves), than any of us had ever imagined we could.

There were no answers because he was reading for something that wasn’t there: what the text was silent about. Today “surface reading” and “distant reading” are fashionable among literary scholars. Those were not his methods. In the classroom, he ventured into white space, edges, the repressed, the forgotten, the immanent, the impossible: what was high and far away. And to approach those topics, even to recognize them as topics, you had to get not just close to a text but inside it.

Harold understood that literature was about a contest for cultural authority. Therefore, it was about power and rhetoric, and it was written by real people in history, with biographies. After the New Criticism, this was a radical innovation. The fact that he made that innovation at Yale, the home of the New Criticism, was significant: his own theory of influence emerged from the struggle to produce it. It opened the way for feminist (think of Gilbert and Gubar) and political criticism of various stripes—which he deplored theatrically, and for so long you can forget he had once been the iconoclast.

Jenn Lewin, Lecturer, University of Haifa:

I first became obsessed with Harold Bloom’s work as an undergraduate; my professors at Brandeis had studied with him. Then, as a graduate student at Yale, I enrolled in two of his legendary courses: on Shakespeare and on contemporary poetry. If by then Bloom’s theory of influence had long been at the center of his presence in the literary world, his presence in the classroom was an amazing phenomenon to witness. It both was an embodiment of Wallace Stevens’ “never-resting mind” and, reminiscent of Whitman, it “contained multitudes.” Bloom would enter the seminar room early and fill the chalkboards with whatever passages he wanted to work through with us, more often than not from memory. After reciting them aloud, he’d proceed to shift between explanations of what he loved in the poem or play in front of us and questions he asked for our help in answering, questions that gave us a glimpse at once of his capacious mind and of a strong and genuine desire to do this work together. Teaching was a way to stave off the loneliness of, among other things, looking for answers on his own. And he didn’t want students to come to his conclusions, he wanted this process to enable students to find their own truths in what they read. A true Emersonian, he knew that what works for one mind does not necessarily hold for another.

Bloom’s books put these passing moments into forms that fortunately abide, making his teaching and his writing of a piece. He once wrote, “When I was very young, I read poems incessantly because I was lonely and somehow must have believed they could become people for me. That vagary could not survive maturation, yet the quest persisted for a voice I had heard before I knew my own alienation.” Books consoled Bloom, as much as they could, in his abiding sense of sadness about the world; sharing his ideas with others was and is one way to cure that sadness. Now, as his readers, we should not cease in our quest to find a similar solace, after his death-solace in his books and in the literature we love. Whenever I called, or wrote, or stopped by to visit him and Jeanne, in the decades since graduate school, he would refer to me by the nickname he had given me back then: “the Yiddishe Isabel Archer.” Though it shows his confidence in my sense of adventure, it is still bewildering to think of life without him. His writings, however, usher us into that new life, by passing on his belief in the power of the imagination to console in our loneliness.

Ernest Suarez, David M. O’Connell Professor of English at the Catholic University of America:

For Harold Bloom, reading and interpreting literature were supremely creative acts—most of us would embarrass ourselves if we approached literary interpretation in a similar manner. But Harold was rare and unique: a critic who became part of the literary canon, yet wasn’t a seminal poet, novelist, or playwright. His impatience with professional schools of criticism—especially with sociologically oriented, deterministic theories—sprung from his embrace of the imagination and creativity as life-giving forces. Existing literary forms couldn’t contain William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf or Ralph Ellison’s fiction, or T. S. Eliot’s early poetry, or Robert Penn Warren’s late poetry. And existing forms of criticism couldn’t—and can’t—contain Harold’s responses to great literature. All of these figures had precursors, of course, but the power of their imaginations, their mastery of language, and engagement with their materials gave birth to works singular and fecund.

I first met Harold at a dinner party at R.W.B. (Dick) and Nancy Lewis’s home about twenty-five years ago, and we developed an easy rapport based on our love of literature and of the New York Yankees. Almost all of our communications included these topics. He was generous and kind whenever we met, and occasionally would surprise me with a phone call. He loved hyperbole and rejoiced in how it could spark conversation, laughter, and insights. He was a genius who understood genius, and who cherished how great literature deepens and extends humanity. When I read his work, my understanding of literature is strengthened and I’m energized, even when I might quibble or disagree.

Helen Vendler, Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor Emerita, Department of English, Harvard University:

I was in graduate school, and Harold was beginning his first year of teaching at Yale, when we met. I was walking through Harvard Yard with a friend doing graduate work at Yale when she suddenly greeted a man sitting in a heap on the grass: “Harold!”

As we talked, Harold began talking about, and quoting, the poetry of D. H. Lawrence, which I didn’t know: “Reach me a gentian, give me a torch!” We remained friends.

For Harold, the prophetic tone was the most convincing, and it was no accident that Hart Crane—“O Thou steeled Cognizance”—was his first poet, nor that Shelley—“To hope till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”—was the subject of his dissertation. (His appetite for that tone led him to be unfair to some poets, notably T. S. Eliot—“A churchwardenly purveyor of myths of historical decline.”). Harold could be mischievous in his epithets. When he read my book on Herbert, he said that he had previously thought that Herbert “had only two tones, querulous and faintly querulous.”

Raised in an orthodox house, he first heard poetry in the voices of the biblical prophets and he heard their voices echoing in Milton, Blake, Shelley, Yeats, Lawrence, and even (because of the publication of The Changing Light at Sandover) James Merrill.

The second half of Harold’s career centered on Shakespeare, in whom he heard not a prophetic tone but rather the human voice in all its varieties, comic as well as tragic. The soliloquies, he thought, created modern introspection. In Falstaff he found a self-image different from his earlier prophetic one, one incorporating comedy, irony, and pathos.

Not everyone who took a supercilious tone about Harold’s commercial undertakings (such as the Chelsea House series for which he wrote countless introductions) knew that he was supporting, at enormous personal cost, a disabled son.

I always admired him for that particular heroism as well as for his possession of the full range of English and American poetry (whether he liked it or not). I’ll never forget reading, in The Anxiety of Influence, the revelatory “six revisionary ratios,” in which he mapped the ways one poet could transform the work of a predecessor.

Harold was a powerful influence on his contemporaries as well as his students.

Like Milton, a “sect of one,” Harold at Yale became, thanks to Bart Giamatti, a unique department of one. And although he and I differed on the worth of some poets, we both agreed with Gautier in thinking that “Le buste Survit à la cité,” that the long chain of aesthetic creators created our world, rather than the reverse—that artists were constructed by their historical and political contexts. Although we were never colleagues, we were always glad to see one another, and I will miss his genius and his presence.

Poet Rosanna Warren:

In his writing, his speaking, his very being, Harold was a great Teacher: provocative, often outrageous, and to use one of his favorite words, daemonic. Expounding Shakespeare or Emerson, the Bible or Cormac McCarthy, he invited his listeners to scorch our hands in the fire of literature and to accept the elemental encounter. It wasn’t a matter of agreeing or disagreeing with Harold: it was a matter of participating. As he wrote in the just-published The American Canon, “Poems matter only if we matter.” His parting has made, as Shakespeare wrote in Antony and Cleopatra, “a gap in nature.”

Dr. Jesse Zuba, Department of English and Foreign Languages, Delaware State University, and co-editor of American Religious Poems:

By the time I met Harold Bloom as a grad student at Yale, his picture had been on the family refrigerator—alongside photos of cousins, magnets, grocery lists—for years. I had discovered The Western Canon as a college freshman. Pulled along by Harold’s infectious enjoyment of Shakespeare, Cervantes, Dickinson, and others, I read it over and over. I visited my professors time and again, but never to talk about their work, only Harold’s. I read Yeats, The Anxiety of Influence, The Visionary Company, and Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. I changed my major to English. When a grad student who knew Harold told him about my obsession, he wrote to her: “Tell the young Zuba to forsake the mere neo-Johnsonian Bloom for Sacred Samuel himself.” I photocopied the letter and showed it to everyone I knew.

I introduced myself in person when I found Harold walking the halls of Linsly-Chittenden, where he’d arrived nearly two hours early for his seminar. Later he called and left a message asking me to visit him at home. When I arrived, he’d just gotten off the phone with Don DeLillo. We drank sherry and watched the end of a Yankees game (“Throw him a wicked curveball, Mariano.”) He told the story of how W. H. Auden once came to stay overnight and brought only a bottle of vodka, a shaker, and a martini glass, all stored in a briefcase that was his only luggage. We listened to Bud Powell’s “Un Poco Loco.” I went home with a signed copy of Poetry and Repression and a handwritten recipe for “Deli Brisket” from his wife, Jeanne. I couldn’t believe my good luck.

Eventually I became one of his research assistants. While Harold went through surgery and rehabilitation, I was tasked with drafting a table of contents for American Religious Poems, to be published by the Library of America. For months after showing him my initial list, Harold constantly added more—often after reciting a few lines from memory to illustrate a poem’s worthiness. Once, trying to test him, I suggested including Michael Wigglesworth, whose work I barely knew. He frowned and rolled his eyes, and then he recited a couple stanzas from “The Day of Doom” before agreeing: “Well, child, if you insist.”

But Harold’s extraordinariness was less a matter of his legendary memory than it was of his way of interpreting poetry as if there were nothing more important in the world. That and his generous devotion to the people in his life, including his many students. “We have lost our Bloom. We are the fruit thereof.” He will be very much missed.

More on Harold Bloom

Benjamin Ivry in The Forward

James Romm at The New York Review of Books

Marco Roth at n + 1

James Wood in The New Yorker

Lucas Zwirner at The Paris Review