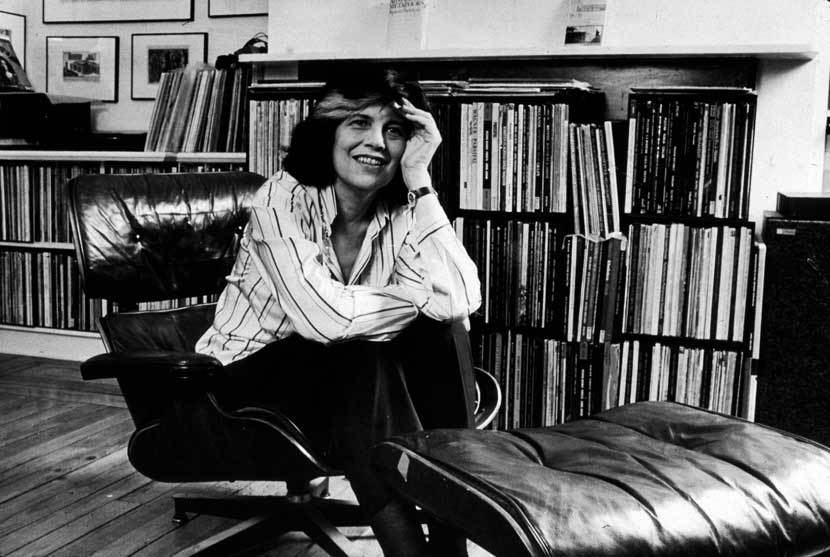

With this year’s Met Gala, whose theme was “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” Susan Sontag returned to the center of cultural conversation—a place, arguably, she’s never really left. The evening was inspired by Sontag’s landmark essay “Notes on Camp,” published first in the fall 1964 issue of Partisan Review and then in book form in her classic 1966 collection Against Interpretation (reissued by Library of America in 2013). That a fifty-five-year-old work of cultural criticism could still instigate such an event suggests something of the power and prescience of Sontag’s writing. Some fifteen years after her death, Sontag is as emblematic and enigmatic as ever, and she remains one of the most seminal intellectuals of our time.

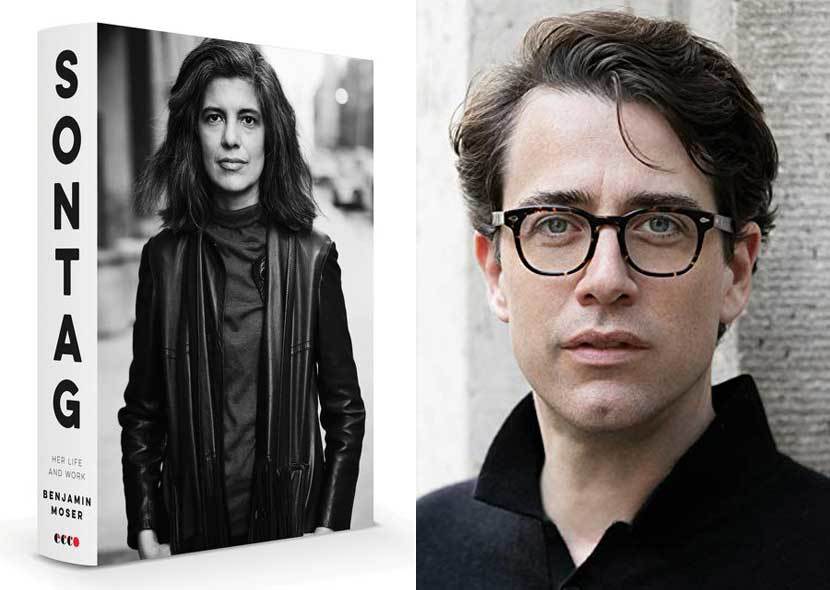

As Benjamin Moser shows in his remarkable new biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work, this preeminence took a heavy toll on Sontag. The story of Sue Rosenblatt’s rise from suburban obscurity in southern California to become Susan Sontag, the embodiment of avant-garde cosmopolitanism, is impressive and sometimes poignant, but her agonizing insecurity as she struggled to inhabit the persona she had created is perhaps doubly so. She once remarked that “I’m only interested in people engaged in a project of self-transformation.” This proved a high bar for her family and her many lovers, but for no one was the bar set higher than for Sontag herself.

Deeply impressed by his acclaimed 2009 life of the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, Why This World, the Sontag estate approached Moser to become Sontag’s authorized biographer. This allowed him access to her extensive archives, much of which remains off limits to the general public, and to interview many people who have never before spoken in detail about Sontag, including Annie Leibowitz. The result, in the estimation of Sigrid Nunez, is “an astonishing page-turner” and “the last word on Susan Sontag.”

As his long-awaited biography goes on sale this week, Benjamin Moser was kind enough to take a few moments to answer some questions about Sontag and her legacy.

Library of America: Did you have reservations about undertaking the daunting task of telling this complicated and conflicted life, which necessarily involves putting Sontag’s far-ranging works in the context of their time and of her larger project? It’s hard to imagine a more challenging subject.

Benjamin Moser: I love a challenging subject, and especially one as exciting as Sontag. On the intellectual side, a life of Sontag is a history of modern art, literature, politics, medicine, sexuality, psychology, and philosophy. So you get to learn about all that. And on the personal side, you get to write about a larger-than-life character—and one who surrounded herself with the most fascinating, accomplished people of her time. Maybe I was a bit naïve at first—excited rather than daunted. But I had written a biography before, of Clarice Lispector, so I think I knew what to expect. The most daunting thing remains writing a book that does the subject justice.

LOA: A central insight of your book, one that uncovers new layers of meaning in Sontag’s criticism, is that “Sontag’s most personal works are precisely those in which she most determinedly elides the ‘I.’” Why, in contrast to a writer like Joan Didion, for whom the first person was such a powerful tool, was Sontag so careful to keep herself at one remove?

Moser: One of the most interesting discoveries I made when writing this book was how often she seemed to write about herself under other names. In this sense, I hope this biography will be like a Rosetta Stone to help people decipher her work. Many of her portraits of other writers are as much about herself as they are about their purported subjects. And when she writes about cancer, in Illness as Metaphor, she never mentions how recently she had almost died of the same disease. There’s an emotional electricity pulsing just under the surface. A more memoiristic approach might dilute that.

LOA: Library of America readers might be surprised to learn that the American writer who left the deepest imprint on young Sue Rosenblatt was Jack London, especially his novel Martin Eden. Why was this book so important to her?

Moser: I myself hadn’t read Jack London since high school—The Call of the Wild—and I loved reading Martin Eden for this book. (Another reason it’s great to write about Sontag is that she opens the door to an unbelievable range of culture, from fiction to philosophy to music to dance to history.) Like her and like Jack London, Martin Eden was a kid from California who dreamed of the writing life. He fights against philistinism, has a brief moment of success, and then kills himself. “Many of my conceptions were formed under the direct stimulus of this novel,” she wrote. The novel is essential to understanding her thought.

LOA: In the 1970s Sontag wrote a series of essays on different aspects of feminism, particularly the fraught concept of “beauty,” which you call “among the best essays [she] ever wrote.” And yet, as you note, she never collected them, and they were not published in book form until the Library of America edition appeared after her death. Why do think Sontag chose not to include these pieces in her books?

Moser: The choice really stands out, because she collected so many other things. My theory is that the essays came at a moment of cultural change, when feminism was losing a certain momentum in the patriarchal New York world of which Susan was a part. She was often criticized as an “exceptional woman,” lucky enough to be exempt from the barriers that held other women back. In the seventies, there was a reaction against overtly feminist writings. The movement went from strength to strength in universities, in psychology, in law, in the project of restoring the female past—especially the female artistic past. But in the world Susan inhabited, it exposed writers to critical violence. The essays were mothballed. It’s too bad, because they’re excellent.

LOA: As we turn to our last question it’s comforting to know we’re not alone: “After Sontag’s death,” you write, “when new phenomena arose that demanded interpretation, people often wondered what she would make of them.” No one has written with as much penetration about photography—about the tension between image and identity, representation and reality—as Sontag. We can’t help but wonder what she would make of the current mania for recording lives online, often in the minutest detail. Would you care to speculate on Sontag on the selfie?

Moser: A really great writer is one whose work becomes even more relevant with time. Sontag gives us a key to so many things that seem hot off the presses. It turns out the issues that made Sontag love and hate photography are the same things people worry about now, but in a different form: How much of yourself should you show, and how much should you keep for yourself? What is the difference between posing voluntarily and being exposed, without consent, to the eye of the voyeur? These questions were being asked, in different guises, as far back as Plato: the tension between reality and image. Considering the life and work of Sontag is a way to use the past in order to read the future.

Benjamin Moser is the author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, a finalist for the National Book Critic’s Circle Award and a New York Times Notable Book. For his work bringing Clarice Lispector to international prominence, he received Brazil’s first State Prize for Cultural Diplomacy. He has published translations from French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. A former book columnist for Harper’s Magazine and The New York Times Book Review, he has also written for The New Yorker, Conde Nast Traveler, and The New York Review of Books.