Our guest post today comes from Christoph Irmscher, professor of English at Indiana University, Bloomington, editor of the Library of America volume John James Audubon: Writings and Drawings, and author of the biography Max Eastman: A Life (Yale University Press, 2017).

Irmscher is the literary executor for Daniel Aaron (1912–2016), the pioneering scholar of American studies who was the founding president and a life trustee of Library of America. Irmscher recently established a website dedicated to preserving Aaron’s legacy; in the following essay, he shares his findings from transcribing the journal Aaron kept as a Fulbright Ambassador to Poland in 1962 and 1963. The journal is a major document of the work Aaron did as a cultural ambassador at the height of the Cold War, and the pages in question build to Aaron’s eventual realization that “countries taking different paths, marching to the rhythm of different drummers, can still be in shouting distance of one another, and the shouts don’t have to be insulting.” A longer and somewhat different version of this essay will appear in Ideas Crossing the Atlantic, to be published next year by the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

By Christoph Irmscher

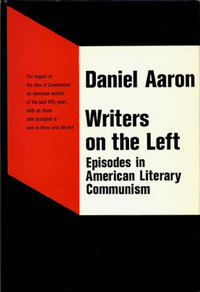

In 1961, Daniel Aaron published Writers on the Left, a study of recent American writers who had flirted with the idea of communism—a somewhat scandalous project in a nation that had barely emerged from the red–baiting of the 1950s.

To achieve what he had been asked to provide—as complete a picture of the “visitable past,” in Henry James’s phrase, as he could manage—Aaron had to invent his own method. He later said that his inspiration had been John Dos Passos’s trilogy U.S.A. Alternating between “group narratives” (narratives about organizations, magazines, and institutions, as well as explanations of literary history) and stories about individuals or “representative men,” he created a rich, complex tapestry of the 1930s and ’40s. Almost inevitably, he submerged his own point of view under the opinions of his subjects, and his political position remained murky. As Aaron admitted later, Dos Passos’s “Camera Eye” was largely absent from his book.

But maybe it is helpful to think of Writers on the Left as a peculiarly Melvillean book rather than a piece of intellectual synthesis and to see Aaron as inspired by Melville’s Ishmael, who made the transition from “schoolmaster to a sailor” when he joined the crew of the Pequod. Writers on the Left was Aaron’s version of F. O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance, but his gathering of exemplary writers was retrospective, not forward-looking. Instead of magisterially defining a proudly American canon for future readers, all he had been able to do was “offer a few clues to the mysteries of the recent past,” as Aaron wrote in the 1964 paperback edition: a humble attempt to preserve, for readers in the 1960s, what was already slipping away.

In 1962, Aaron formally reversed the passage from schoolmaster to sailor when he went to Poland as a Fulbright Lecturer, his first extended experience of living in a communist country. He had felt the proximity of Russia during the year he spent teaching in Finland in 1951–52, when a secretary at the Soviet embassy had unsuccessfully tried to recruit him as a spy. American embassy officials were stunned by his naïveté. When Aaron arrived in Poland in August 1962, he had just turned fifty and considered himself wiser. In the spiral-bound notebook journal he kept, he made a promise to himself early on: he wanted to be an ideal visitor, not “The Suspicious ‘Don’t Take Me In’-American,” who “arrives with firm convictions about Marxist political theory, totalitarianism, clichés about the Soviet bloc—with the view that socialism or soviet communism is the same wherever it takes over and that Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, East Germany etc. are basically the same.” This type of person would come to Poland with his head swirling with stories of “Polish perfidy,” bugged hotel rooms, tapped phones, and beautiful female spies ready to pounce. Clad in the impermeable armor of their “realism,” fancying themselves “hard-boiled political sophisticates,” the Don’t-Take-Me-In Americans would insulate themselves against too close contact with actual people. By contrast, the ideal visitor opens his eyes and ears, letting the impressions flow, no matter the political system: “the mirage of socialism, or capitalism, or Catholicism should never blot out the realities of people.” He would truly get to know the country (January 6, 1963).

Clearly, Aaron’s research for Writers on the Left had prepared him for his visit: If the interviews he had conducted for the book were any indication, there was no one-size-fits-all approach to communism. It helped that he had come by himself; his wife Janet Summers Aaron, who almost three decades earlier had been among the first group of American students to visit the USSR, wouldn’t join him until December. From the beginning of his stay, Aaron went out of his way to meet people, at parties, in his apartment building on Aleje Jerozolimskie in the center of Warsaw, on trains, and in the streets. He assiduously worked on his command of Polish, beginning, after a while, to write out the dates in his journal in Polish. Teaching American literature at Warsaw University was not an easy gig, to be sure: Aaron found his students little prepared or motivated for actual study and their linguistic skills deficient (November 18, 1962).

Determined to live up to his notion of the ideal visitor, Aaron quickly noticed that Poles tended to be friendly but reserved when they met foreigners. It is interesting to see how, even at a rather early stage in his visit, he sought to come up with reasons for that invisible wall—not a “high wall,” he insisted—that separated him from them. For Aaron wanted to understand Polish reserve from both his perspective and that of the Poles themselves. Imagining what a Pole might say to a foreigner, he became, at least in his imagination, that Polish citizen: “The Pole easily looks across and smiles at the westerner. You see, he seems to be saying, it is possibly wiser for both of us to be circumspect. Not, mind you, because we fear anything in particular.” The great watershed in recent Polish history, the uprising of 1956 that had swept First Secretary Władysław Gomulka into power, had loosened the rigid hold of communism on the country but had only increased worries of more hidden threats. “If we seem too friendly, too eager,” Aaron’s imaginary interlocutor continues, “well, this might be misinterpreted so let’s see each other on official occasions—and then perhaps—when we’ve had the chance to size each other up—we can meet more informally. I know you’re not the kind of American who will return home and write an article about your Polish experiences which will compromise the Poles who—out of mistaken trust—were indiscreet and said unwise things—but then, you see, we can be sure. And there is still so much at stake for us here” (December 11, 1962).

In his journal, Aaron is very good at evoking the damp, dismal days of fall in Warsaw, the moist climate of worry that seeps in through one’s pores in a city where even the American ambassador has to escape to a forest preserve outside the city limits when he wants to have a conversation without the authorities listening in (September 29, 1962). Aaron was expecting to be conscious of his Americanness during the year. What he wasn’t ready for was the extent to which the Poles constantly reminded him of his Jewishness. The anti-Semitism of even the intellectuals he encountered troubled him and put considerable pressure on his resolve to be the ideal visitor. It didn’t make much of a difference to him that his interlocutors seemed focused on Polish Jews, as if they still resented the latter group’s return to Poland after the war. When it came to Jews, definitions of Polishness were restrictive, he learned, in a way definitions of Americanness tended not to be. Polish Jews could never pretend to speak for, or represent, Poland. Even a liberal, sophisticated friend confided in him that the Jews, in his opinion, contaminated the Polish gene pool (February 17, 1963).

And yet, overall, Aaron was deeply impressed by the fundamental kindness of the people he met. The Poles, he decided, made lousy communists; their nation, composed of fierce individualists, was as unsuited to communism as one could only imagine. In a letter to the German–born Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann he copied into his journal, Aaron wrote that he was beginning to think that Poland wasn’t “a nation at all, but a sprawling collectivity of idiosyncratic individuals held together by some sort of political mystique. If ever a nation was unfitted—temperamentally, emotionally, politically—for socialism, this is it.” It was hilarious to think that the Soviets had hoped to transform this country: “On top of all this assorted human material sits the Party apparatus attempting to make all this imprecision precise. . . . ideology triumphs magnificently over common sense.” The spectacle was, Aaron concluded, “at once poignant, comic, and disturbing. Quixotism is more significant than Marxism” (January 20, 1963).

Polish individualism suited Aaron just fine, and he began to settle into a routine that involved meeting his classes and spending his Sunday mornings drinking weak tea or bad coffee at the Dom Turisty on Novy Swiat, a grubby hotel right across from the statue of Copernicus that always smelled of varnish: “I check my coat, enter the empty kawiarnia [coffeehouse], and write for several hours in my journal,” he told Kaufmann. The “mercurial Poles” remained a subject of infinite interest to him. The flip side of their individualism was the daily scramble for survival, since there was never enough of anything, the rudeness it brought out in normally kind people, “the timidity with which an aspirant for anything from a room to a passport peeps into an office and prepares himself for the insolent reception he is very likely to get” (January 20, 1963).

But even as the communist bureaucracy and the sufferings especially of writers and professors under socialism led Aaron to question his own lingering socialist sympathies, he remained more perturbed by the way his own country sought to demoralize the Poles by constantly advertising the American “testament of plenty.” In his journal, Aaron was withering about the attempts of American cultural diplomacy—what he called the “American ‘Mission’”—to convert the Poles away from communism by baiting them with an exaggerated version of the West, the “America of glittering perspectives.” So that they may win minds, Americans “must tell the truth about ourselves.” If the United States saw fit to give loans to developing countries, why not offer loans to “underdeveloped minds” (March 23, 1963)? Americans should limit their goals to what is realizable, and Aaron did his own by beginning to smuggle books, on subjects not officially sanctioned, into the library of the Polish Academy of Science.

***

The longer Aaron stayed in Poland, the more clearly he realized that he could never be “the perfect interpreter of the New Poland.” His Polish remained halting, and “American conventions” were too deeply ingrained in him to get full access to the truth about the Poles. But he still felt that he was ahead of other American observers before him, such as John Kenneth Galbraith, Daniel Bell, or Lionel Trilling, and he dismissed the numerous other members of the “battalion of one or two week junketeers who see and hear just enough to be completely . . . misleading when they write about Eastern Europe” (March 4, 1963). Just a few years earlier, in his introduction to an anthology of writings from Poland, Trilling had announced there was a possibility that Polish intellectuals, given their strong anti-Russian bias, might eventually succeed in getting “a considerable measure of freedom to be established in Poland under national communism.” Galbraith had lectured in Poland four years earlier, and subsequently published the journal he had kept, in which he praised Polish laundry services (his shirts, he said, came back “cleaner than the Harvard Coop ever got them”) and lamented the shabbiness of Polish life. His verdict was similar to Trilling’s: it was impossible to reconcile the “very high state of intellectual life” in Poland with the low level of economic life. The result was paralysis, and a country full of high-achieving thinkers yearning to go west: “A ‘Ford Fellowship’ is the new Jerusalem.”

Aaron’s assessment of his own ability to understand the Poles was free of such pontificatory certitude. Rather than taking the high road, he had been “sniff[ing] around the edges” and thus getting short looks behind “the flamboyant Polish façade.” The only thing he knew for certain was that, with Poland, there was nothing to be certain about: “I know Party people and innovators and peasants and counts. And I have acquired a number of ‘informants’ whose explanations as to what is really going on are impressively contradictory.” Aaron became obsessed with finding the “pin of truth” hidden in the “haystack of error” that everyone knew communism was (March 4, 1963). That separated him from someone like Galbraith, who, with impressive self-deprecation, once described the attitude of Americans to socialism as akin to their attitude to sex: “There is deep fascination, a desire to look, and if possible to touch, but no desire to become involved.”

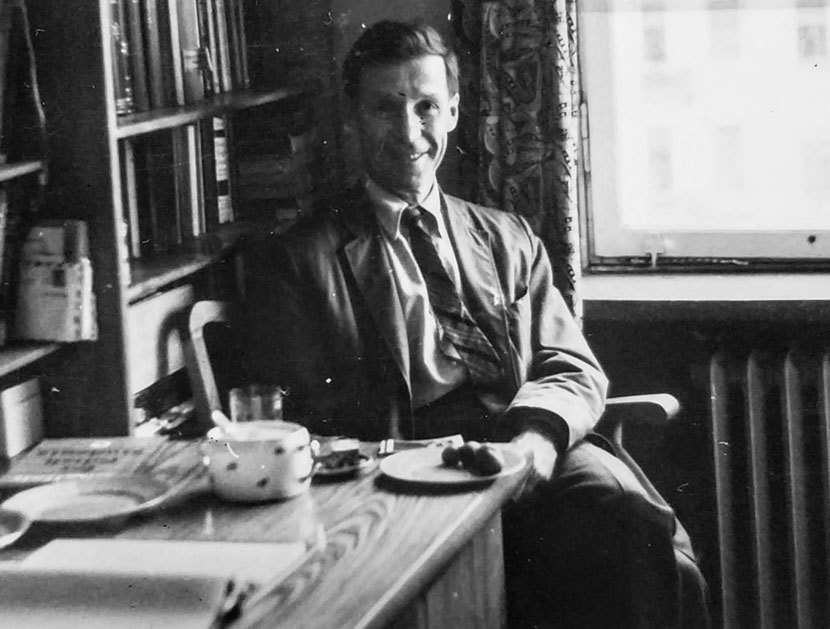

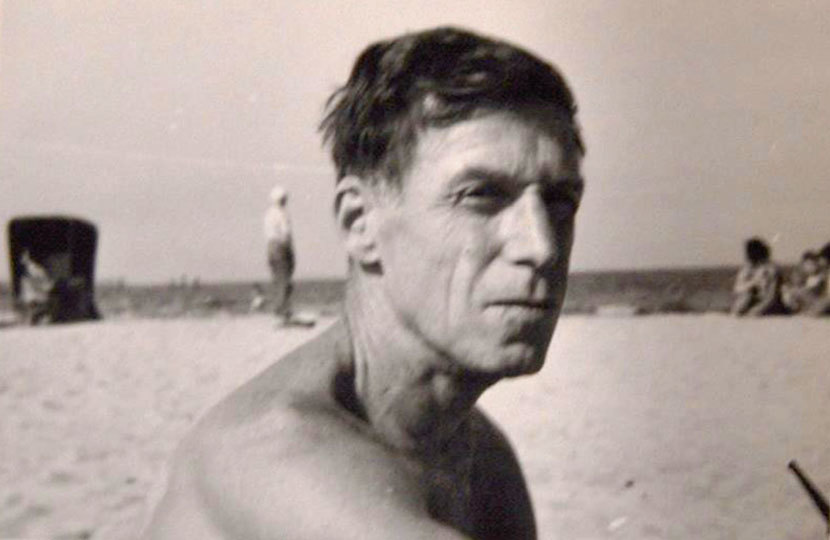

There is very little that is unrestrainedly personal in Aaron’s Polish journal. His wife’s arrival is mentioned briefly, as is her impatience with the deprivations of life during the Polish winter: lack of hot water, delays in the delivery of coal and therefore no reliable heat, and empty shelves in the grocery stores. But several photographs in Aaron’s papers reveal the degree to which he at least did become immersed in Polish life, allowing the schoolmaster to be replaced by the sailor. A series of such pictures was taken, according to the inscriptions on the back, in the summer of 1963 on the white sand beaches of Sopot, near Gdansk. They are obviously private in nature: in some of them, Aaron is sleeping, while in others he’s half turned toward the camera, reluctant to pose yet not. These are different images from the one [above, top] in which a smiling Aaron is posing, fully suited, in in his office at Warsaw University, the very model of the affable American visiting professor.

Aaron’s Polish journal builds toward a conclusion at which the photographs from Sopot only hint. Throughout the year, Aaron takes infinite pleasure in the people he meets, treating them with a kind of quiet delight at the fact of their existence. The scenes recounted in Aaron’s diary have the wondrous normality of a Kafka novel, in which one expects strange things to happen as part of the ordinary daily business of getting on with one’s life.

Early one morning, having just moved into his nondescript apartment in Warsaw, Aaron is woken up by the unfamiliar sound of a bell. He describes what happened next: “I leaped out of bed, conditioned fire-horse that I am, and went first to the telephone. Buzz. Then to the door—which I opened as far as the guard chain would allow.” Out in the dim corridor he spies the figure of a woman, who immediately wants to know if “Ann somebody” lived there. A cascade of Polish words follows. “I explained I was newly arrived, that I was American, that I understood no Polish.” But this does not deter the visitor. More volleys of Polish words follow: “At last, good naturedly, she begged my pardon and retired into the cold and fog—after ringing some other doorbells. I looked at the clock when I climbed back into bed. It was 5:30.” Not a word of complaint, condemnation, or anger. Instead, Aaron accepts this woman’s presence outside his door and her subsequent disappearance into the Warsaw fog as if these were the most natural things in the world (October 6–7, 1962).

Once his Polish has gotten better, Aaron finds out more about the men and women he encounters. But he always leaves the basic mystery of their lives intact, conveying a sense of wonder at how such people manage to carry on at all. Take the two men he meets at a bar in Radość, a suburb of Warsaw. One of the men has “a ravaged Hawthorne face”: stubbly, unshaven, the thin, refined skull crossed by a livid scar. Dressed in discarded company clothes, he has a long glass of vodka before him. His companion—big moustache, heavy leather overcoat—is “solicitous, quiet, worried.” With sad, weepy eyes, “he gloomily surveys his outrageous friend, whose mutters blossom with shouts against the militia, the Bolsheviks, Russia.” Every other sentence uttered by Hawthorne Face is a curse, addressed to no one in particular. “I must teach these militia with their Russian uniforms righteousness,” he shouts. Aaron finds out from the man’s droopy-eyed friend that he is visiting from Gdansk and that he suffered a head injury during the 1956 turmoil. In his former life, he had been a professor, a Doctor of Philosophy, a “kind and wonderful man,” though that might not be so evident now. As Aaron, horrified that someone like himself, an academic, could end up imprisoned in such irrationality, turns toward him, the ex-professor utters another curse and then, abruptly, gets up: “His cap on at a rakish angle, he fills his canteen with vodka, gives me a beautiful smile—and leaves with his solicitous friend.” There is so much in that beautiful smile, given to Aaron that night by a man everyone else would have seen as just another angry drunk: recognition of their shared humanity, of the fact that dignity, after most everything is gone, may lie in the way you put on your hat (March 17, 1963).

***

Aaron left Poland at the end of June 1963. He spent a few days lecturing in Germany, which proved to be an anticlimax. Living in Poland had increased his sense of his own Jewishness, but in an odd way, Aaron’s out-of-placeness was not a problem in a nation where everyone seemed somehow ill at ease. Being a Jew in Germany was different, and Aaron’s journal records his surprise at the powerful reaction he had to seeing the former perpetrators of the Holocaust live so exceedingly well. Munich was, he observed on July 4, “full of food, cars, well-dressed people.”

What the Poles, shivering in their ill-fitting clothes, displayed only too readily, Germans tucked away under layers of “good quality clothes,” glass and stone and gleaming metal: “underneath . . . the emptiness and anxiety.” The “thick mantle of prosperity” collectively worn by the German nation made him sad rather than angry, and it didn’t help that he felt that his lectures were “unwanted and probably unnecessary.” The Poles had sloughed off their responsibility for genocide, too, but their depressed manner of living, for Aaron, had somehow become a way of doing penance for what happened. Post–1956 Poland was a state of mind, rather than country; its chaotic unloveliness had given Aaron an uncanny sense of home that the gleaming facades of Munich could not. Nor, for that matter, could his own countrymen: “Heidelberg is full of yelling Americans—and a disagreeable place it is” (July 4, 1963).

For two thirds of a century Aaron was a cunning observer of the twists and turns of history. But he wasn’t an ungracious one as he kept imagining the possibility of a united world in which people talk to one another across national or geographical boundaries. In a “Self-Interview,” delivered as a talk at Smith College after his return from Poland, when the last remnants of his socialist faith were gone, Aaron declared: “Countries taking different paths, marching to the rhythms of different drummers, can still be in shouting distance of one another, and the shouts don’t have to be insulting.” Let us think, he says, of ideas not as weapons but as bridges, as points of integration and reconciliation. This was as much an admonishment directed at his own government as it was an assessment of Polish politics.

For decades afterwards, Aaron modeled the “articulate dialogue” he recommended in his post-Poland lecture. His small kitchen in Cambridge, with its malfunctioning stove and the torn red-and-white checkered tablecloth, became a meeting place for people from all walks of life, academics and non-academics, activists and conservatives, clutching mugs of strong instant coffee or the occasional glass of whiskey. Talking gave Aaron pleasure. But above all, he liked to listen. His kitchen at Farwell Place around the corner from Harvard Square was a kind of indoor agora and remained so pretty much until the day he died, on April 30, 2016, just a few months shy of his 104th birthday.

Notes

Quotations in this essay are taken from Daniel Aaron’s Polish Journal, 1962-63, now at Houghton Library, Harvard University. Aaron alternates between English and Polish in dating his entries; for the sake of consistency and accessibility I have translated the Polish instances.

For more on Aaron’s lecturing abroad, see his own account in The Americanist (University of Michigan Press, 2007). Unpublished material cited in this essay, including the photographs, are from the Daniel Aaron Papers, Houghton Library, MS Am 2951, and appears by permission of the estate of Daniel Aaron (Christoph Irmscher, literary executor). The photograph of Aaron in his Warsaw office is from the collection of Christoph Irmscher.