By Tom Carson

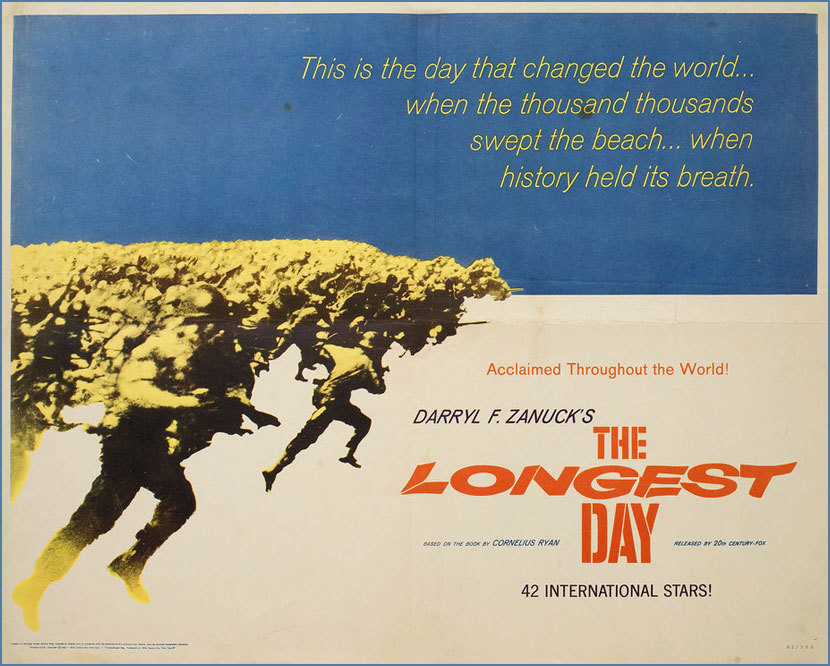

Producer Darryl F. Zanuck was no artist, but his star-studded CinemaScope facsimile of D-Day, based on the Cornelius Ryan book, doesn’t dishonor the event itself.

“Never had there been a dawn like this. In the murky, gray light, in majestic, fearful grandeur, the great Allied fleet lay off Normandy’s five invasion beaches.”

It’s hard to imagine any twenty-first-century historian writing church-bell prose as concisely fustian as that scene-setting passage in The Longest Day, Cornelius Ryan’s 1959 reconstruction of the D-Day landings from the perspectives of hundreds of American, British, Canadian, French, and German participants. But Ryan wasn’t a historian by training or even proclivity, at least not primarily. He was a master of quasi-reportorial, cracklingly written, emotionally compelling historical narratives, and they were hugely popular with the big, non-specialist reading public because they deserved to be. The Longest Day remains the most beloved of his World War II chronicles in large part because it’s his jauntiest, all but bereft of the ambivalence and melancholy of his later The Last Battle and A Bridge Too Far.

Along with spectacle and a well-thumbed thesaurus of stirring adjectives, human interest was his meat. The technique of using multiple eyewitness anecdotes to produce a reportorial mosaic of a pivotal day in history most likely originated with John Hersey’s Hiroshima, and it had been popularized by Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember (the Titanic going down, as remembered by sixty-two survivors) and Day of Infamy (Pearl Harbor). On a smaller scale, Ryan himself had tried it out in, among other articles for Collier’s magazine, “Five Desperate Hours in Cabin 56,” his account of the Andrea Doria’s 1956 sinking. But his big advantage this time around was that The Longest Day was a celebration, not a requiem. Put it this way: very little about reading Hiroshima is likely to thrill twelve-year-old boys, much less make them unspeakably eager to join the United States Air Force.

That sort of appeal made Ryan’s book a natural for Hollywood, with a couple of major difficulties. Earlier World War II movies, such as Raoul Walsh’s Battle Cry (1955), had featured climactic combat sequences on a scale only enabled by the military services’ cooperation. But nobody had tried to put a whole invasion on film. On top of that, despite teeming with vivid incidental characters, Ryan’s saga featured no leading ones to help the audience keep its bearings.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Cornelius Ryan: The Longest Day, A Bridge Too Far |

Cecil B. De Mille’s crowded Bible epics were the nearest equivalent in more than one sense. Enter Darryl F. Zanuck, who had recently stepped down from heading 20th Century Fox to work as an independent producer for the studio instead. The Longest Day became his passion project while Fox was reeling from the costs of Cleopatra’s interminable birth. Possibly, nobody except Zanuck would have had the connections, clout, and stogie-chomping determination to induce the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet to stage a gargantuan mock beach landing—in Corsica, not Normandy, but you can’t have everything—and talk the U.S., British, and French governments into contributing sizable contingents of troops to impersonate their wartime predecessors. (Understandably, West Germany’s Bundeswehr sat this one out.)

Zanuck also set out to solve the nothing-but-incidental-characters dilemma by rounding up an almost preposterously gaudy all-star cast to festoon the screen with cameos. Listing which international box-office draws of 1962 aren’t in The Longest Day would use up less space than enumerating those who are, from Germany’s Curt Jürgens to Richard Burton (on a busman’s holiday from Cleopatra) and recent West Side Story alum Richard Beymer. Plus, inevitably, ringer John Wayne, who got paid ten times more ($250,000) than any of his co-stars for under ten minutes of screen time.

A lot of The Longest Day is clumsy, veering without warning from inanely over-emphatic to perfunctory to bungled. Excessive time is spent, for instance, belaboring how the German high command was in possession of a tip-off to the invasion’s imminence, but failed to act on it—the kind of supposedly mordant historical irony that always clutters the screen to no purpose. (It’s much more effective in the book and was one of Ryan’s D-Day scoops, which may explain why nobody had the nerve to propose omitting it from the movie.) One seriously doubts that the seasick, frightened G.I.s in the first wave ashore began lustily cheering once they hit the beach. No doubt to appease Charles de Gaulle’s government, the part played by the Free French in liberating their country is more exaggerated than Toto’s contribution to The Wizard of Oz. And so on.

Even those of us with a helpless (and lifelong) affection for the lumbering thing have to be in a forgiving mood to remember that nobody had tried to make an epic quite like this one before. From Here to Eternity author James Jones, who worked on the script with his pal, French novelist Romain Gary—as did several other writers including Ryan himself, who gets the main “Screenplay by” credit in part, perhaps, to placate him—later remarked that the movie was primarily faithful to the original event because of the staggering logistics involved in mounting both.

That’s why only Zanuck, not the movie’s trio of credited directors—Andrew Marton handling the American sequences, Ken Annakin supervising the British ones, and Bernhard Wicki overseeing the kerfuffle on the German side—can be reckoned as The Longest Day’s auteur. What you might call his peekaboo “DARRYL FECIT” signature is the inclusion in the cast of Irina Demick, his mistress at the time, as French Resistance heroine Janine Boitard, whose genuine real-life courage involved events considerably less gaudy than her screen stand-in’s glamorized tussles with German soldiers.

Calling the movie’s other performances variable amounts to an act of battlefield triage. The many actors on hand to lackadaisically pick up a check—Burton, Rod Steiger, Roddy McDowall, and so on—are jostled by the relative few, like Jeffrey Hunter, who are doing their best to sketch an evocative characterization in their two or three quick scenes. Then there are the performers maximizing the impact of their invasion vignette by hamming outrageously, with the young Sean Connery and the not-so-young Red Buttons—playing paratrooper John Steele, who famously got hung up on Ste.-Mère-Église’s church steeple and had to play dead for hours—among the worst offenders.

Funnily enough, considering what lengths Zanuck went to procure his services, John Wayne is God-awful. Blatantly a quarter-century too old for the character, he rants paunchily in a way whose tiresomeness insulted the original’s memory. Or would have if the original—82nd Airborne battalion commander Benjamin Vandervoort, one of D-Day’s genuine heroes—hadn’t still been alive to see and be dismayed by the travesty.

In any case, Marton was plainly no director of actors. Nor was Annakin. Because Wicki had more on the ball, his actors—Jürgens as General Blumentritt, Hans Christian Blech as the artillery major who first sees the Allied invasion fleet offshore, and Heinz Reincke as irreverent Luftwaffe flier “Pips” Priller, among others—are at once more flavorful and more measured. Granted, they’re all on the wrong side, but at least they aren’t crass about it.

Otherwise, the sequences that everybody remembers are virtually wordless: the massed parachutes spookily descending on Ste.-Mère-Église at two a.m., the rope-climbing assault on Pointe du Hoc, Priller and his wingman’s quixotic strafing run over the British beaches. (The thousands of invaders down below were too stunned to even try shooting the two planes down.) The movie’s best claim to grimy grandeur is the protracted re-creation of the near-debacle on Omaha Beach, where Hunter and poor old Eddie Albert meet their maker while trying to help Robert Mitchum’s stalwart Brigadier General Norman Cota save the day.

James Jones was irked enough by requests to sanitize the “excessive slaughter” to angrily ask Zanuck, “What did they think Omaha was, if not a ‘bloodbath’?” But even though Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan was truer to the gore quotient, The Longest Day is much more accurate about how long the ordeal went on. Although the movie beefs up Mitchum’s role by omitting the similar heroics of Colonel George A. Taylor in rallying the dazed troops on his share of the beachhead, including filching one of Taylor’s most famous quotes and putting it in Cota’s mouth instead, the salvage of the Omaha landings is rightly The Longest Day’s climax, because D-Day might well have failed if that linchpin beach in the middle of the invasion zone hadn’t been secured.

All in all, The Longest Day is about as square as a movie this idiosyncratically assembled can be, which doubtless helps account for its box-office success. Outdoing even Lawrence of Arabia, it was the biggest hit of 1962, and remained the most moneymaking black-and-white movie of all time until Schindler’s List displaced it over thirty years later. We’ll never know what might have happened if Samuel Fuller, a D-Day combat veteran who had about as much use for conventional uplift as draft-deferred John Wayne (whom he loathed) did for pacifism, had accepted Zanuck’s offer to direct the whole behemoth. Luckily, Fuller got to do his own version of life and death on Omaha Beach in The Big Red One, a movie as intransigently crazy as The Longest Day is heartily anodyne.

It may go without saying that Darryl F. Zanuck was no artist. But give him credit for this: his CinemaScope facsimile of D-Day didn’t dishonor the event. Me, I’ve spent almost fifty please-don’t-call-them-obsessive years chortling at The Longest Day’s most idiotic moments, including Paul Anka’s cheery theme song: “Many men came here as soldiers/Many men will pass this way/Many men will count the hours/As they live. . . the Longest Day!” But I won’t be a bit surprised if I wind up humming it on my deathbed.

1962 trailer for The Longest Day (3:05)

The Longest Day. 1962. Directed by Ken Annakin, Andrew Marton, and Bernhard Wicki. Screenplay by Cornelius Ryan, from his book, with additional contributions by Romain Gary, James Jones, David Pursall, and Jack Seddon. With Richard Burton, Irene Demick, Gert Fröbe, Curt Jürgens, Robert Mitchum, and John Wayne, among many others.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

A two-time National Magazine Award winner for criticism during his stint as Esquire magazine’s “Screen” columnist, Tom Carson is the author of the novels Gilligan’s Wake (2003) and Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter (2011). He previously wrote about the George Roy Hill adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five for The Moviegoer.