By Farran Smith Nehme

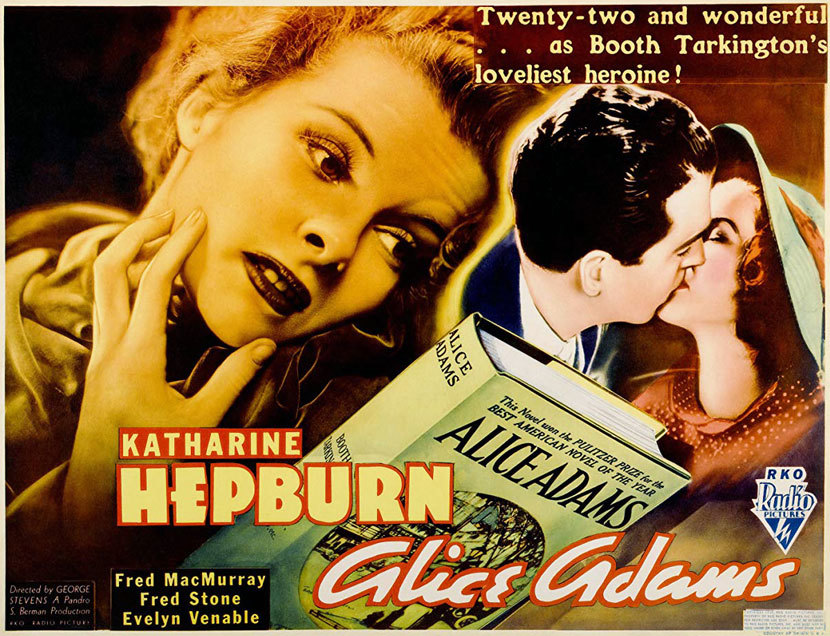

Katharine Hepburn’s incandescent performance ensures that audiences love the titular heroine perhaps even more than her creator, novelist Booth Tarkington, did.

Social humiliation—say, a young woman mocked and ignored at a party where she had dearly hoped to make an impression—stabs the heart in a unique way. The pain of wanting to belong when you do not is so intense that experiencing it in something like Alice Adams, novel or film, is an almost physical agony. The first time I watched George Stevens’s 1935 film, and saw the light in Katharine Hepburn’s eyes slowly go out when her Alice realizes not one of her hopes for an elegant evening at wealthy Mildred Palmer’s home will come true, my throat went dry and I felt as though something was crushing my chest. The lie she tells upon returning (“Did you have a good time?” “Yes, lovely, Mother”) and the weary walk to her bedroom is even more heartbreaking than the tears she sheds once she’s safely inside. Who could watch this and not remember every youthful moment of being ignored or taunted—who indeed, except perhaps the Mildred Palmers of this world.

Hepburn’s Alice is sympathetic from the first, just by virtue of being played by Katharine Hepburn, beautiful but coltishly awkward, intelligent yet obtuse, her youthful nerve endings almost visible on the surface of her skin. But Booth Tarkington’s Alice sneaks up on the reader. As in the movie, Alice is fond of her father, Virgil, and inclined to shield him from her shrewish mother. Mrs. Adams can’t forgive the man for being what he is, a mid-level employee who has risen as far in life as he ever will; that is, until Mrs. Adams nags her husband into a series of rash and ultimately doomed attempts at becoming a glue tycoon.

But Alice is, in another sense, her mother’s daughter, in that she’s absorbed the notion that their small comforts are drab and hardly worth having. Alice leads “a life of gestures,” practicing expressions in the mirror. She becomes someone else as soon as she steps outside the house, as when, finding herself observed by a likely young man, Alice pauses to inspect a bit of masonry on a house in a rich neighborhood, trying to give the impression that this is where she lives.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Booth Tarkington: Novels & Stories |

Tarkington’s novel is considerably darker than the film. “My most actual and ‘life-like’ work,” he wrote soon after its publication, “about as humorous as tuberculosis.” While few if any viewers would rate George Stevens’s movie higher than the somber masterpiece that is Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, there are many critics and readers who find Alice Adams the greater novel. Its characters undermine each other and most of all, themselves, in ways described with piercing accuracy by Tarkington, as when Alice finds herself lying to Albert Russell, the rich boy she loves (played in the movie by Fred MacMurray): “. . . even as she rattled on, there was somewhere in her mind a constant little wonder. Everything she said seemed to be necessary to support something else she had said. How had it happened?”

Bryn Mawr alumna Hepburn was herself patrician, yet the yearning and self-deluded Alice is one of her finest and most believable creations. Perhaps the recent course of her career had given Hepburn more insight into what it means to have things out of reach. She was coming off a couple of particularly dire movie flops; before that, there had been her Broadway appearance in The Lake, where the reviews were calamitous and onstage, she said, “I could actually feel the attention of the audience recede like the tide.” That sounds a lot like what happens to Alice’s hopes for a future with Alfred during the catastrophic dinner party she throws in an effort to impress him.

The novel Alice Adams focuses on class and aspiration in a Midwestern city, one that is spreading and darkening like the town in The Magnificent Ambersons, becoming colder and more impersonal in the process. Stevens’s movie is essentially a portrait of Alice, and remains firmly sympathetic to her even as it plainly shows her snobbery and affectations. Alice’s optimism is irresistible, as in the opening, when she solves the problem of needing a party corsage she can’t afford by gathering a bouquet of violets that grows beside a sign forbidding anyone from picking the flowers. Also lovable are Alice’s flashes of honesty, the yearning and sense of her own daring when she tells Alfred, “I decided that I should probably never dare to be myself with you; not if I wanted you to see me again.”

All the details of the final dinner party are Tarkington’s: the stifling heat, the uncomfortably formal clothes, the sickeningly heavy food, and the gleefully incompetent maid. But while the book’s scene feels almost tragic in its roiling catalog of mishaps, Stevens retains more humor, notably in the person of Hattie McDaniel as Malena, the rented help. Tarkington’s “colored” characters are almost always tiresome stereotypes, and in script form perhaps Malena is too. (They even misspelled the actor’s name on the credits as “Hattie McDaniels,” where she is listed last though her part is certainly more significant than Hedda Hopper’s society matron or arguably even third-billed Evelyn Venable as Mildred.) But McDaniel is so funny, as she elbows the doors open like a Teamster making a delivery, chews gum, snarls her lines, and lets her lace cap flop where it will, that it’s impossible not to conclude that Malena is engaging in her own subversive form of protest.

Tarkington’s ending is not tragic, nor even as sad as it could have been; Alice will work hard for a living, she will eventually be alone, but no longer will she be nibbled to death by the complaints and demands of her family. There is, literally, a light shining as she climbs the stairs to Frincke’s Business College, on her way to a life in office work: “Half-way up the shadows were heaviest, but after that the place began to seem brighter. There was an open window overhead somewhere, she found, and the steps at the top were gay with sunshine.”

But this finale is simply not the romantic one that movie audiences wanted in 1935 (and often still do). Stevens and Hepburn argued with Pan Berman, the movie’s producer at RKO, to retain Tarkington’s ending, as had the 1923 silent version directed by Rowland V. Lee. Berman enlisted George Cukor to pitch a happy fadeout to director and star, and the talk did the trick. The result, with Alfred back on the porch to embrace Alice, may not be true to Tarkington, but Cukor knew it would satisfy audiences who, at the end of the film, love Alice perhaps even more than her novelist creator did.

Alice Adams (1935). Directed by George Stevens. Written by Dorothy Yost, Mortimer Offner, and Jane Murfin, from Booth Tarkington’s novel. With Katharine Hepburn, Fred MacMurray, Hattie McDaniel, and Evelyn Venable.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu • Watch on YouTube

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film at her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and in a column for filmcomment.com. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, The Criterion Collection, and Sight and Sound. She has previously written about Intruder in the Dust, The Haunting, and Little Women for The Moviegoer.