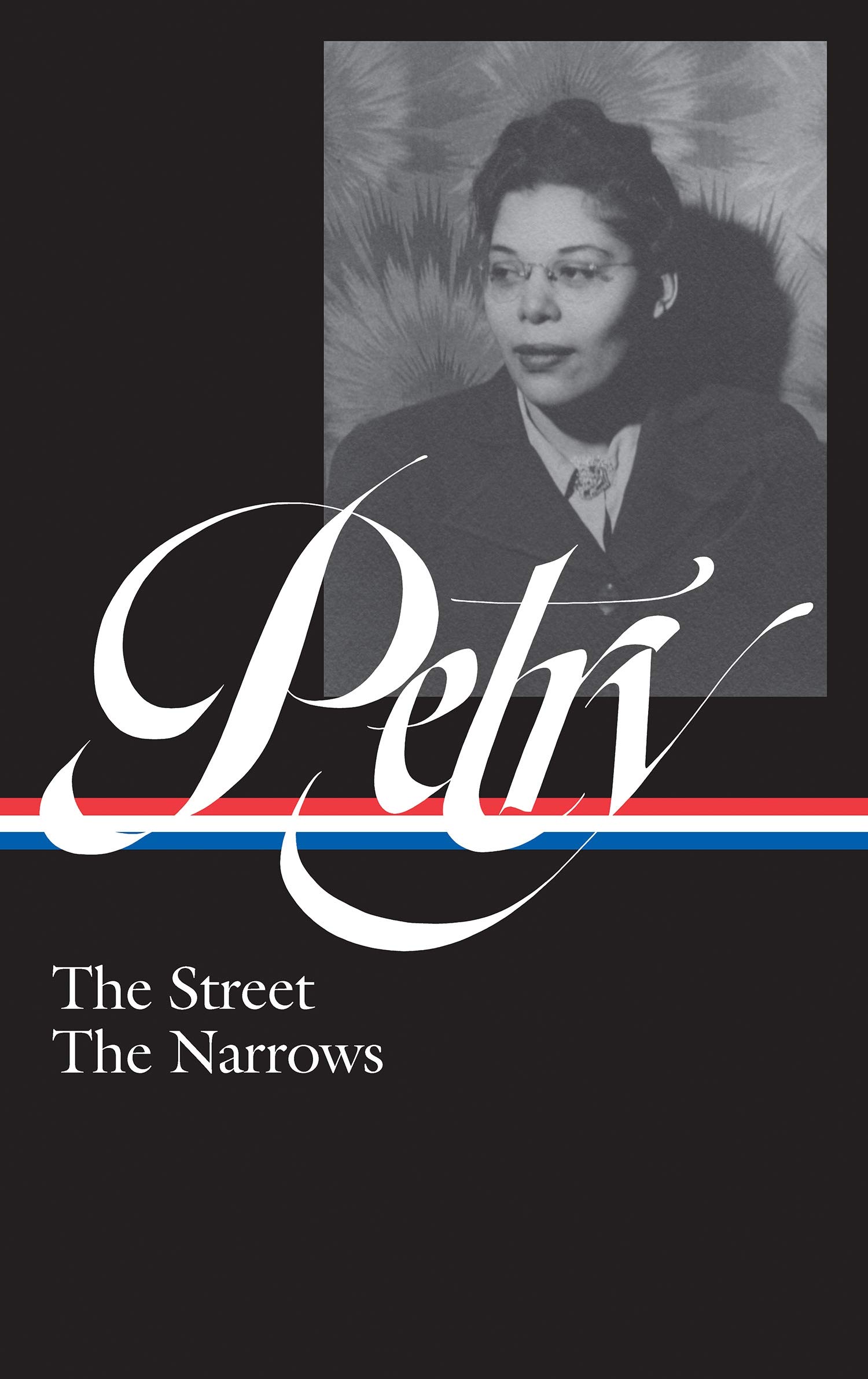

This winter Library of America published Ann Petry: The Street, The Narrows, bringing together the two major novels of a mid-twentieth-century African American author whose work had been comparatively neglected in recent decades.

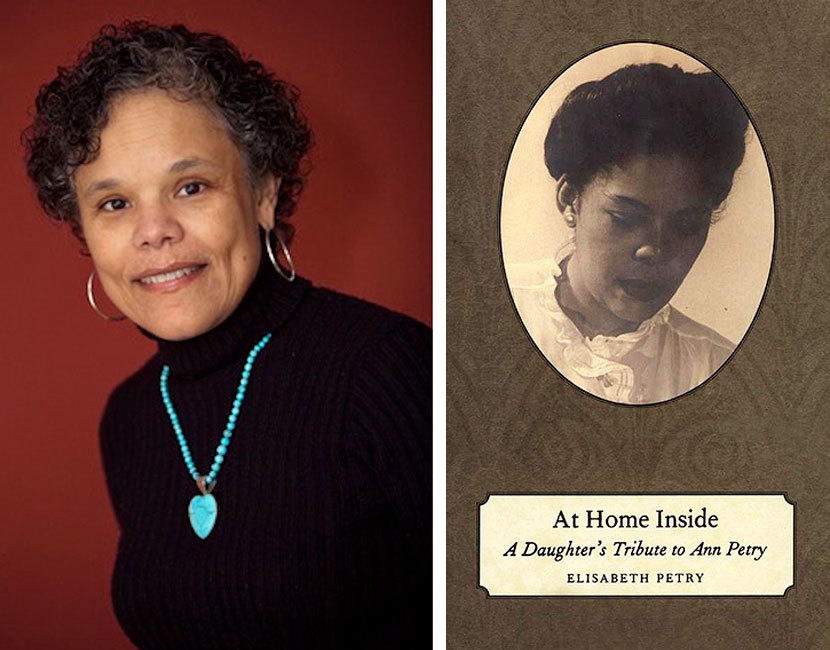

Since many readers of the new Library of America volume will undoubtedly want to learn more about Ann Petry, we turned to her daughter Liz Petry, whose 2009 book At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry (University Press of Mississippi) is an engrossing combination of personal reminiscence and literary detective work. Liz Petry retraces her mother’s younger days in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, before delving into the Harlem years that made her a cultural celebrity—a period that would remain a mystery to Liz for nearly the whole time she was growing up. At Home Inside also makes adroit use of Ann Petry’s journals to chart the inner world of a fiercely private writer whose “innate reticence,” Liz Petry writes, “meant that she kept an emotional distance even from those she loved.”

Via email, Liz Petry answered a few of our questions about her mother’s life and career.

Library of America: Your mother’s years in Harlem provided the material for the book that made her famous, The Street (1946). But as your memoir At Home Inside makes clear, afterwards she remained notably quiet about that period in her life. Is her 1949 essay on Harlem, which she wrote after she moved away, a reliable reflection of her complicated feelings about the city?

Liz Petry: With the caveats that I was born after she left New York and that she destroyed much of the material about that period in her life, I would say yes, “Harlem” accurately reflects her feelings about the area that inspired The Street and a number of her short stories. The essay is at once a condemnation of the policies that allowed it to fester through decades and a love letter to the people who managed to overcome the poverty, crime, and oppression to make significant contributions to modern American life.

LOA: Your book also shows how your mother juggled an impressive number of roles and responsibilities: In addition to being a writer, she was a mother and wife, a dedicated homemaker, and an active citizen in her local community. Do you think being the kind of writer who shuts herself off from the world simply didn’t appeal to her?

Petry: I believe my mother had a thoroughly ambivalent attitude toward shutting herself off from the world. On the one hand, she used solitude to produce The Street and many of her short stories. She found privacy utterly lacking when my parents moved to Connecticut, especially after I was born.

On the other hand, some journal entries indicate she did not enjoy living alone while my father was serving in the Army. More significantly, she lived her mother’s instruction, “You must leave the world a better place than when you entered it.” Hence my mother exhausted herself taking care of her family, nurturing friends, and engaging in public service.

LOA: At Home Inside suggests that your mother seemed notably ambivalent later in life about being rediscovered and lauded, not once but several times. How do you think she would have felt about the new Library of America edition?

Petry: She begrudged the press interviews that accompanied the 1992 edition of The Street, but she very much wanted the widest possible audience to receive the message. She was especially proud of The Narrows (I agree with Farah [Jasmine Griffin] that it’s her masterpiece), so I think she would be thrilled at this gorgeous new edition of her works as long as no one tried to interview her about it. She might consent to do a Q&A like this one because it preserves a certain level of anonymity, but she would refuse book tours, photographs, or recordings of any sort, audio or video.

LOA: Was the fluctuating level of her fame a challenge for her? Might she have been happier to remain in relative anonymity all along?

Petry: I’m not sure if the fluctuating level of fame was a challenge. I think she was willing to trade a certain level of public presence for the dissemination of her ideas, especially the messages concerning racism, sexism, and class divides. The problem was that people invaded her privacy in myriad ways. As with many authors, readers assumed they knew her because they had read her works, and in most cases she was far too polite and genteel to drive them away.

LOA: Ann Petry’s essay “My Most Humiliating Jim Crow Experience,” written for Negro Digest in 1946, is an is an important document recalling when she was seven years old and she and her classmates had to leave the local beach because she was black. How candid was she about those kinds of experiences with you, either when you were growing up or when you were an adult?

Petry: We never discussed her experiences. I didn’t learn about them until I read the essay and entries in her journals as an adult. She used actions, not words, to protect me from the same treatment. She joined the school board in Old Saybrook where she saw to the hiring of the first African American teacher and staff member. She made certain that an English teacher did not put white kids in blackface for a high school production of The Member of the Wedding. She maintained the property her parents had purchased one lot over from the town beach so that I never had to suffer the same humiliating Jim Crow experience.