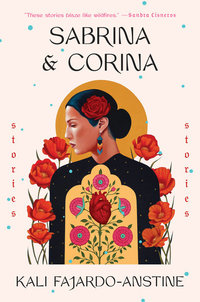

Our latest Influences guest post by a contemporary writer comes from Kali Fajardo-Anstine, whose debut short story collection, Sabrina & Corina, is published today by One World/Random House.

In Sabrina & Corina, Fajardo-Anstine draws on her family’s storytelling traditions to relate the struggles of a frequently overlooked population in today’s West—indigenous Latinas, who struggle against violence, poverty, gentrification, and other forms of marginalization. Some prominent writers have already taken notice: Joy Williams calls Sabrina & Corina “A terrific collection of stories—fiercely and beautifully made,” and Sandra Cisneros says that Fajardo-Anstine’s stories “blaze like wildfires, with characters who made me laugh and broke my heart.”

Below, Fajardo-Anstine pays tribute to Arturo Islas (1938–1991), author of the novels The Rain God (1984) and Migrant Souls (1991). Islas’s third novel, La Mollie and the King of Tears, was published posthumously in 1996.

“Felix Angel, Mama Chona’s oldest son, was murdered by an eighteen-year-old soldier from the South on a cold, dry day in February. . . .”

The Rain God is a masterful and heartbreaking novel. It is a subtly moving realist portrayal of Chicanos in the Southwest and one of the primary influences on my debut collection, Sabrina & Corina. The Rain God offers a portrait of the Angel family, spanning three generations in the desert.

Arturo Islas would only publish two novels, The Rain God and its companion work Migrant Souls, before he died from complications of AIDS in early 1991. He was the first Chicano to sign a publishing contract with a major house. His work explores the sadness and beauty of the Southwest, and it is robust in its inclusion of queer Chicano characters. Islas writes in sonically clean prose. His setting, a fictional town on the Texas-Mexican border, is vivid and sorrowful. His characters are idiosyncratic, nuanced, and felt, at least by this reader, as if they are real.

I was first exposed to The Rain God during college as a Chicana/o Studies minor when I took a class on the Chicano novel. I hadn’t heard of Islas before, and I remember, after reading the first pages of The Rain God, that I felt dumbfounded, almost angry, that such a gifted and distinct voice had somehow been hidden from me. The 1991 paperback edition of the novel I have is nearly disintegrated, the glue along the spin yellow and brittle with age, whole sections of the book spilling out like chunks of loose hair. Inside the back cover, to the left of a somber yet handsome photo of Islas, I wrote elegiac notes on the seven deadly sins as I saw them presented throughout the novel—Mama Chona and her pride, Felix and his greed, and so on.

When I worked as a bookseller, I was often asked by customers for recommendations, novels that were highly readable that dealt with collective themes, those concepts Faulkner referred to as the old universal truths—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Most of the time, I offered up The Rain God and was moved when customers would return weeks or months later to tell me how attached they had grown to the Angels, the pain they felt while reading the novel, but also the joyous laughter they experienced within its pages.

Islas represents the best in American literature, a voice that is regional and individual, crafted and labored over. His obsessions with death and family are intricately worked out on the page in dazzling, often understated realist prose. “The culture I come from is not afraid of death in the sense that it’s not afraid to pay it homage, it’s not afraid to pay tribute,” Islas told the Stanford Humanities Review before his death. “That doesn’t mean we are mournful grieving people. It means that you can’t have life without a sense of your mortality.”

Plagued by illnesses nearly all his life, Islas was intimately connected to his mortality. He was at work on a third novel when he died at home in Stanford.

Denver native Kali Fajardo-Anstine received her MFA from the University of Wyoming and has won fellowships from Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony. Her writing has been published in The American Scholar, Boston Review, Bellevue Literary Review, The Idaho Review, and Southwestern American Literature, among other outlets. Fajardo-Anstine is currently working on a historical novel as her follow-up to Sabrina & Corina.