Library of America’s latest anthology, Dance in America, brings together dancers and choreographers, impresarios and critics, and enthusiastic literary observers to present a kaleidoscopic portrait of a great art form. Edited by the veteran dance writer Mindy Aloff, the book tells the story—through more than a hundred selections spanning two centuries—of how dance took on fresh life with new, vital, and distinctly American innovations and adaptations.

Aloff is Dance Editor of The University Press of Florida and has taught dance criticism and history at the Macaulay Honors College of CUNY (at Hunter College) and at Barnard College. She is a former editor of the Dance Critics Association News and serves as a consultant to The George Balanchine Foundation. The author of Dance Anecdotes: Stories from the Worlds of Ballet, Broadway, the Ballroom, and Modern Dance (2006) and Hippo in a Tutu: Dancing in Disney Animation (2008) and the editor of Agnes de Mille’s Leaps in the Dark: Art and the World (2011), Aloff has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Village Voice, and The New Republic, among many other outlets.

Via email, we interviewed Aloff about Dance in America just ahead of its publication earlier this month.

Library of America: In your introduction, you write that Dance in America “was not intended as a book of greatest hits by hall of famers.” Can you elaborate a little on what you mean by that?

Mindy Aloff: Gladly. A “greatest hits” approach would require including pieces that are too long, too familiar, too expensive, or too arcane to be interesting to the general reader. If you wanted to put out an anthology of “greatest hits” relating to dance in America, you’d have to include some of the writings of aesthetician Susanne Langer because her legacy is so pervasive, even for writers and dancers who never heard of her. Then you’d have to include the “Burnt Norton” section of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, a poem of universal veneration, where dance indicates a concept rather than a practice, and Edwin Denby’s game-changing essay on the photographs of Vaslav Nijinsky, which has been so widely reprinted that it’s included in other anthologies from Library of America. The same is true of Albert Murray’s chapter “The Blues as Dance Music,” from his widely admired and widely available collection Stomping the Blues, a crucial contribution for a dance hall of fame.

You’d have to include other major essays from the landmark 1940s monograph series Dance Index, which the Eakins Press has just made easily available in its historical entirety online—essays such as Ann Barzel’s 1944 “European Dance Teachers in the United States,” a unique history of the origins of ballet in America. For range of research, no subsequent history of American ballet pedagogy can touch this one-hundred-page monograph. And among the greatest hits, I think you’d have to include the full version of Lillian Ross’s “Dancers in May,” her majestic Reporter at Large story that follows one public school teacher over an academic year as she introduces a class of Lower East Side fifth graders of diverse heritages to six European folk dances, which they learn and practice for months and then perform at an annual Mayday fête of Manhattan’s public schools, in Central Park. A story that offers dance in America as a democratic ideal, it takes up most of a 1964 issue of The New Yorker and would have occupied a tremendous chunk of our current anthology.

So, instead, I opted for a counter-intuitive compendium of mostly well-known writers and mostly unfamiliar, even unclassifiable, writings on subjects that can be surprising. My first standard for choice was that the prose had to stand on its own, without accompanying illustrations. The accident of inclusion produced some improbable yet provocative associations: Janet Collins on Léonide Massine’s imperial authority and Massine himself on eking out a living at the Roxy, La Argentina in performance as rekindled in awe by Agnes de Mille and the tangos of exhibition ballroom dancer Tony De Marco as portrayed with a smile by Margaret Case Harriman, Black Elk’s sacred vision as embodied in choreography for living horses and Edmund Wilson’s gently profane invocation of the “ponies” at The Follies.

Three highly anticipated books on Balanchine are in preparation—by Arlene Croce, Elizabeth Kendall, and Jennifer Homans. All those authors are represented in our anthology, but only one small writing by Arlene, of her three here, focuses on Balanchine’s choreography. I wanted readers to see that even the most knowledgeable scholar-writers devoted to him as a subject have also written brilliantly on a great range of dancing and dancers.

LOA: The contributors to Dance in America include a number of non-specialists, or names we associate with other contexts, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Dickinson, and George Catlin. Why did you think it important to bring in these perspectives?

Aloff: Unlike art or theater writing, which, in the United States, were thought worthy for cultivated American readers from at least the eighteenth century, dance itself was considered so specialized, or so far outside polite society, or so downright blasphemous, that dance writing of any type, outside technical manuals, isn’t easy to find until the 1900s. Still, beginning in the nineteenth century, one encounters more than we might expect: in poems (Dickinson), journals (Emerson), travel reports by missionaries and adventurers (Catlin). Fiction writers would bring descriptions of dancing into their stories as presentation pieces: Washington Irving, for instance, apparently loved to dance himself, but Irving’s most sustained dance writing that I found discussed European social dancing when he was abroad.

The thing is, most writers—whether they dance or not—are fascinated by dancing, perhaps in part because to bring it back alive on the page presents interesting literary challenges. And, as in the poems and writings of Langston Hughes, included in our anthology, not all of the dance written about is theatrical. Another gorgeous example of such dance writing in our book is George Washington Cable’s long-ago remembrance of the Sunday dancing and music by African American slaves in the Congo Square of New Orleans. Cable not only had a great memory but also a keen eye for fast movement, and that facility is as rare today as in his time. Try it yourself: The next time you watch a dance, see if you can isolate two adjacent steps and then describe them so that a reader who wasn’t there can visualize them. Or, even harder, see if you can describe the way steps and music connect in time for one passage of the dance. Good luck!

LOA: If two canonical names can be said to exist in American dance writing, those names are Edwin Denby and Arlene Croce. What makes their work so distinctive?

Aloff: They speak to the mind and to the ear. They write sentences that are both musical and suspenseful, exciting the reader to turn the page. They both enjoy the same moral center of Balanchine, which gives them aesthetic authority. And their analysis of stage events is extraordinary. Denby—like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, a Harvard drop-out—was a professional dancer, choreographer, student (in Germany) of movement analysis (for a degree in pursuit of which Denby wrote a superb thesis), and an analysand of rigorous psychoanalysis. He was also, most especially, an esteemed poet. And yet, in his dance writings, he brought these experiences to bear gently and with humility, in language a bright ten-year-old could absorb. In addition, he was sparing with metaphors and similes, so that, when he did use one, it was memorable, like a perfect pearl you happen to find in an oyster.

Arlene Croce continues that discipline. She is not a practicing poet, and she never studied dance herself, but she did study art, which gives her a sensitivity to the bodies and stage pictures of the theater. A master of the declarative sentence, she enjoys a first-rate literary gift that was prized when she was still in college. And her early experience as a critic of film gives her a profound understanding of the subterranean elements of drama and of the starlight performances that animate the most “abstract” choreography. Her essay on dance in film was one of the first writings I read by her, back in the 1970s; it introduced me to certain large ideas about dance and the camera, and I never found a survey on that subject to replace hers. As the founding editor of the quarterly Ballet Review, Arlene not only knew Edwin Denby but also brought his voice into her pages. Her essay in this anthology about him as a colleague, a friend, and a giant of her field is, for me, a masterpiece.

LOA: A notable through-line in the book is the attention given to vernacular forms: tap and swing, ragtime and Michael Jackson’s moonwalk, to name only a few of the best-known examples. Did these forms have to wait before they received serious critical consideration?

Aloff: Although visiting ballet superstars in the nineteenth century as well as the twentieth always attracted press attention, as did nineteenth-century touring musical spectacles with ballet, notably The Black Crook, it was not until after World War II that more than a couple of cities in the U.S. enjoyed steady serious criticism by connoisseurs of dance comparable in knowledge and authority to the ballet critics in Russia or Paris. Even in nineteenth-century Philadelphia, there wasn’t enough ballet (or enough interest on the part of the dailies in covering what there was) for a critic to learn a sufficient amount about the art to tell the dancer from the dance.

A pair of unicorns proved the exceptions: Represented in our anthology are Henry Taylor Parker, formally a critic of theater and music in Boston, who wrote many considerate and perceptive reviews of dancers from the first years of the twentieth century into the end of the 1920s, and Carl Van Vechten, a music critic for The New York Times and, decades later, an important photographer of black and white dancers and entertainers. He was reviewing dancers as early as 1910 and continued reviewing dance into the 1960s; by the 1920s, he was writing about vernacular dance in Harlem in his fiction. By 1930, Van Vechten, especially active as a writer and partygoer in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance, was chronicling the acrobatic vernacular dance the Lindy Hop, invented by bravura (and, at the time of invention, amateur) African American dancers. Regardless of how one thinks of his storytelling, his dance writing in every form was serious criticism.

One can find newspaper accounts of dance-driven African American shows that had packed in crowds on Broadway since at least the superstar combo of Bert Williams, George Walker, and Ada Overton Walker in the 1902 In Dahomey. By the early 1920s, a wonder couple, Vernon and Irene Castle, had restyled partnered vernacular dancing from something that lit up juke joints to rituals for white-glove cotillions, Fred Astaire had consulted his revered John Bubbles about tap steps, and Broadway had packed in audiences for Shuffle Along and Runnin’ Wild, which featured the Charleston. But, for the most part, up to the late 1920s, dancers of all vernacular traditions were most knowledgeably critiqued by other dancers.

For viable criticism of the vernacular to thrive, one had to wait for integrated theaters and dance halls, for professional writers to cover dance as a beat, for vernacular dance genres and traditions to be publicly recognized by concert promoters as attractive to paying audiences, and for colleges and universities to offer courses and majors that would make it possible for aspiring critics to learn about the traditions they wanted to evaluate. Writing in The New York Times this past April, in a review of a new work by the white American-born choreographer William Forsythe for the English National Ballet, reviewer Sanjoy Roy offered the following sentences: “Playlist looks as if Mr. Forsythe had asked himself what was the one most powerful force in dance today, and answered: hip-hop. Wisely, he does not imitate it, but lets its spirit infuse the choreography.” Forsythe’s dance interests have evolved in a variety of directions: This passage might have puzzled readers as recently as the late 1980s. As Anna Kisselgoff—chief dance critic of The New York Times from 1977 to 2005—reported in the newspaper in July 1987, Forsythe’s concerns were once quite different. In her review of his Artifact she wrote: “His ‘subject’ is the language of ballet and how that vocabulary can be manipulated, transformed, communicated and examined.”

“Vernacular dance” in America is a term that covers square dancing, Irish step dancing, contradancing, Bollywood dance, belly dancing, the Texas two-step, horas in Jewish weddings, and much else, yet what I’m guessing you’re asking about here is experienced criticism (and critical histories) of tap, jazz, hip-hop, jookin—dances that had to wait for their chroniclers and evaluators because of the racism that severely curtailed how African American dancers were treated by presenters, Hollywood, and the media.

In our anthology, we see informed criticism in Whitney Balliett’s sky-high-wonderful, 1974 portrait of the be-bop rhythm tapper Baby Laurence, or Sally Sommers’s luminous, 2003 appreciation of Gregory Hines, or Alastair Macaulay’s uniquely thoughtful, 2009 capstone assessment of the dancing of Michael Jackson. I underline that these terrific writings are also short; a “greatest hits” anthology would have to bring in passages from some of the splendid book-length histories of vernacular dance by African American and Irish American writers, and it took time for them to appear. Scholars had to emerge who not only love and, often, identify with the dances but who also understood how the technique of the dance forms work and how to look at the dance actions fast enough to identify them as they go by. And the scholars not only had to know how to research cultural subjects in the ephemera of dailies, weeklies, and monthlies but the records themselves had to be made available, along with period films, and publishers had to see the value in sponsoring books on what might be called a specialized or niche subject. Brian Seibert, a hoofer-scholar-critic who just published an articulate and ambitious history of tap dancing that puts pre-twenty-first-century tap dancing in persuasive context, is one such historian. Another is Megan Pugh, a poet-scholar-critic and the youngest writer represented in our anthology.

LOA: In a 1980 piece collected here, we find Susan Sontag declaring, “dance writing has changed essentially in the last decades.” What was the nature of the change she was referring to? And has there been a similar evolution in the years since she made that statement?

Aloff: In her anthology entry, on dance criticism, Sontag writes: “I eagerly read dance writing from and about the past, from Gautier forward . . . . But I don’t recognize dance writing as something I can say yes to, not from a historical point of view but as something that accords with my own experience, until I get to Edwin Denby. His is the first writing that I take seriously as an account of dance, as opposed to an account of someone’s pleasure in dance. Denby describes what bodies are actually doing on stage.” That practice of dance description can be seen as a turning point in dance writing as a field. It certainly didn’t start with Denby, as the Dickens chapter demonstrates, but the former serves as the fountainhead for many subsequent dance critics (including yours truly) who want to learn how to practice dance criticism as a procedure and to reflect on dancing as an art beyond any given era—as a way of answering the most important question in dance writing, namely not “Is it any good?” but “What on earth is it?”

Evaluation is why dance critics are hired; but the ability to pin down elements of identity that make this dance or that dancer unlike any other is why dance writing survives beyond its moment. The critic and historian Deborah Jowitt has compared dance reviewing to writing an anthropologist’s report of a village; Marcia B. Siegel writes reportorial reviews as a professional journalist, albeit with a touch of the memoirist. Both are represented in this anthology.

I knew Sontag a little, and she was a most open-minded and curious intellectual. I think she might revisit her statement about Denby being a turning point in light of the articles and essays here by George Catlin and George Washington Cable and perhaps Dickens and certainly the young Van Vechten. I’m not suggesting that she’d change her mind, of course, but rather that she’d read those contributions seriously—and then, probably, she’d point out something to the effect that what those earlier writers did from time to time, Denby did in every dance review and essay. But she might be moved to change her verb “describes” to “describes and analyzes.” And she might reconsider her slightly dismissive judgment of the nineteenth-century French dance critic Théophile Gautier—often referred to as the first real dance critic—whose many journalistic reviews I think do try to speak with more intellectual distance than Sontag acknowledges, even though their subjectivity strikes me as a tip of the hat to the essays of Montaigne.

LOA: The American dance world lost two irreplaceable figures, Arthur Mitchell and Paul Taylor, as this book was going to press. How are they recognized in these pages?

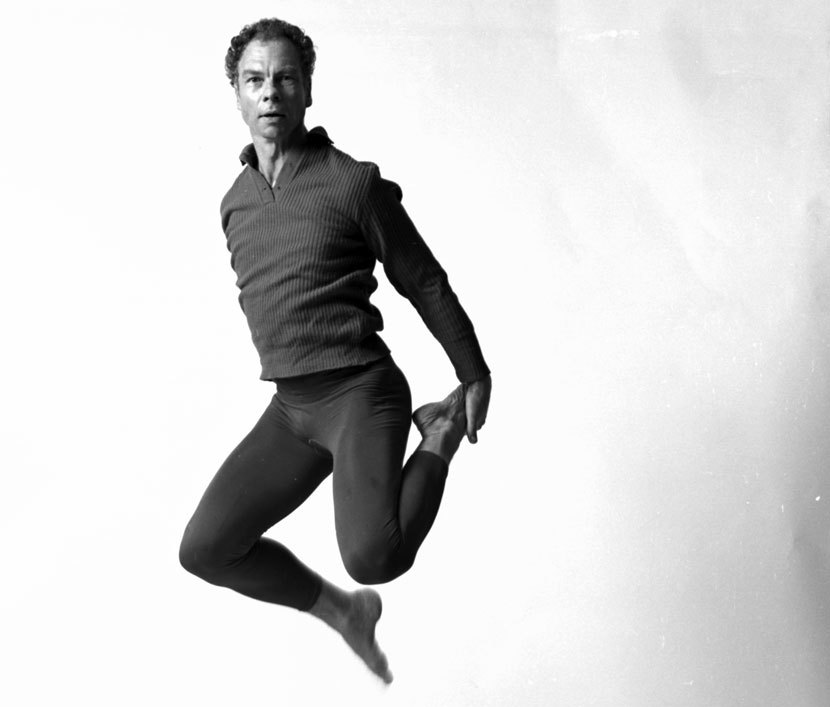

Aloff: Both gentlemen died months after the anthology’s production decisions had been made, although both had been ill for a while. Both are represented in photographs: Paul Taylor in one by Jack Mitchell and Arthur Mitchell (no relation) in one on the back of the dust jacket, by Martha Swope, showing him rehearsing a step with Balanchine—the two of them uncannily identical in the disposition of nearly every angle in that complicated pose. Taylor’s image shows him in an early dance that even I had never heard of; Mitchell and Balanchine, in 1963, are rehearsing the “Phlegmatic” section of Balanchine’s ballet The Four Temperaments. (In her beautiful anthology essay on that ballet, Claudia Roth Pierpont writes, “Lincoln Kirstein described Phlegmatic as ‘fluidly sluggish,’ and Arthur Mitchell—who learned the role from [its originator, Todd] Bolender, said that the real difficulty is ‘to get the accents with the feet and retain fluidity in the body.’”)

Among the writings, Taylor is the subject of a long career-biography/appreciation by the critic Clive Barnes and the author of a chapter from his first memoir, Private Domain, which, as it happens, was edited by Bob Gottlieb—who wrote a foreword to this anthology—when Bob was editor-in-chief of Alfred A. Knopf and so, by fiat (it’s good to be the king!) brought in many stunning books by and about dancers. Taylor—an avid reader—was also a writer of great charm, with a storytelling gift par excellence.

Mitchell is mentioned in several of the entries, including Barbara Milberg Fisher’s nobly told story of how polio seized hold of the ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, Balanchine’s wife for a time and, after their divorce, a member of the faculty at the school of Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem. (Le Clercq, paralyzed by polio in her mid-twenties, for the rest of her life, in both legs and one arm, taught class from her wheelchair.)

A little while before his death, Mitchell transferred his archive to Columbia University, in return for which the very happy school gave him a huge exhibition, put together by Barnard Dance professor emerita Lynn Garafola, who devised an accompanying website. It made me sad that Nancy Reynolds—whose tribute to the Balanchine ballerina Maria Tallchief, Balanchine’s wife prior to Le Clercq, graces our anthology—wrote the definitive essay on Mitchell’s career at NYCB for that site only long after the contents for the anthology had been fixed. However, the up side is that it is accessible online here.