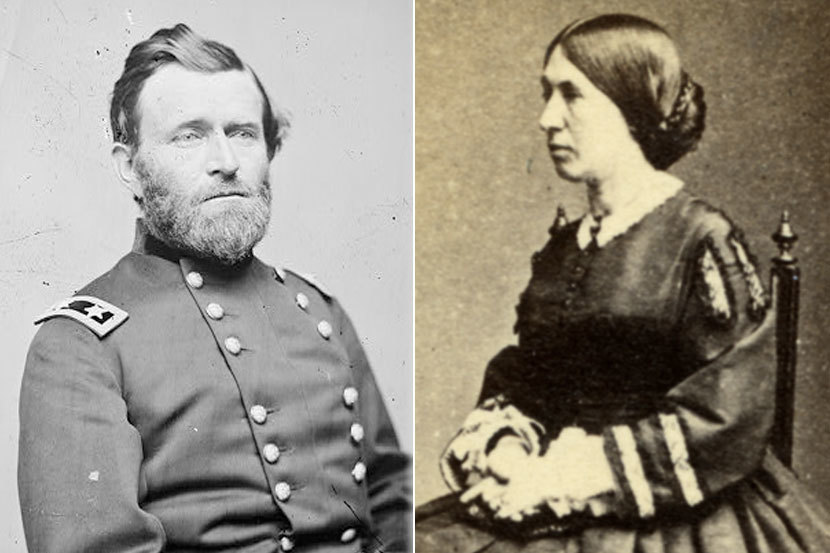

Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War’s greatest general, is celebrated as the author of one of the finest military autobiographies ever written, yet many readers of his Personal Memoirs are unaware that during his army years Grant wrote hundreds of intimate and revealing letters to his wife, Julia Dent Grant.

Library of America’s latest special publication, My Dearest Julia: The Wartime Letters of Ulysses S. Grant to His Wife, collects more than eighty of these letters, beginning with the couple’s engagement in 1844 and ending with the Union victory in 1865. They document Grant’s first experience under fire in Mexico, the homesickness that led him to resign from the peacetime army, and his rapid rise to high command during the Civil War.

Historian Ron Chernow, whose 2017 life of Grant topped the best seller list and won the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, contributes an introduction to the collection in which he writes that these letters “candidly portray Grant’s emotional state, showing his remarkable evolution from an insecure young soldier to a capable, self-confident general. A man so reserved in public needed a private outlet for his feelings, and his correspondence with Julia was the ideal repository for these confessions.”

Below, Library of America Associate Editor Derick Schilling discusses how My Dearest Julia came into being and what Grant’s private letters reveal about him, his marriage, and his conduct of the Civil War.

Library of America: Can you explain why Library of America is publishing My Dearest Julia: The Wartime Letters of Ulysses S. Grant to His Wife?

Derick Schilling: Ulysses S. Grant is no stranger to the Library of America series. In 1990 LOA published Memoirs and Selected Letters, which brought together the Personal Memoirs along with 174 letters Grant wrote from 1839 to 1865 to an array of friends, family members, and military superiors and subordinates. His writing also appears in the four-volume series The Civil War: Told by Those Who Lived It and most recently in Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality. Grant has also been the subject of numerous biographies, including recent major reappraisals by Ronald C. White and Ron Chernow.

In light of the renewed public interest in Grant, Library of America decided to supplement Memoirs and Selected Letters with a shorter special publication that would appeal to readers interested in encountering the private man through the letters he wrote to Julia Dent Grant during their courtship and marriage. The book contains a selection of eighty-five letters and features an elegant and illuminating introduction by Ron Chernow.

(All of the letters in My Dearest Julia have previously appeared in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by the late John Y. Simon and published by the Ulysses S. Grant Association. Readers interested in viewing the handwritten originals can find them online at the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss23333.001_0015_0815/?sp=1.)

LOA: Why the “wartime letters”?

Schilling: Grant only had occasion to write to Julia when they were apart, and it was war, or the prospect of war, that separated them during their courtship and marriage. The first thirty-two letters in the book were written from June 1844 to February 1854. They cover the period when Grant was posted to Louisiana and Texas in anticipation of war with Mexico, the war itself, and Grant’s service in the army after the war. While Grant wasn’t at war in the early 1850s, he was increasingly miserable when his assignments separated him from Julia and their children—bored, restless, homesick, and eventually drinking too much. Barracks soldiering proved harder on him than active campaigning.

The second part of the book contains fifty-two letters written during the Civil War. Once the war ended the Grants were seldom apart for more than a few days, and he rarely had a reason to write to Julia. An exception forms the moving coda to the book—a farewell letter he wrote a few weeks before his death in 1885, and left to be found in his coat pocket.

LOA: Why doesn’t the collection include any letters written by Julia Dent Grant?

Schilling: Julia certainly wrote to him—though not as often as he wished—but her side of the correspondence has vanished. She may have destroyed the letters later in life. We do know that after the runaway commercial success of the Personal Memoirs, Julia proposed to Mark Twain that he publish Grant’s letters to her as a follow-up volume. Twain was initially interested, but his relations with the Grant family cooled for other reasons and the project fell by the wayside.

LOA: What do the letters reveal about Grant’s personality?

Schilling: At first Grant comes across as a lovelorn, insecure young man, constantly seeking reassurances from Julia that she loves him. After he experiences battle in Mexico his confidence increases; he also become more open to the world around him, as he encounters a landscape and culture far different from anything he was used to. His letters in the Civil War are much shorter, streamlined by the burdens of command, but he always finds time to ask about the children.

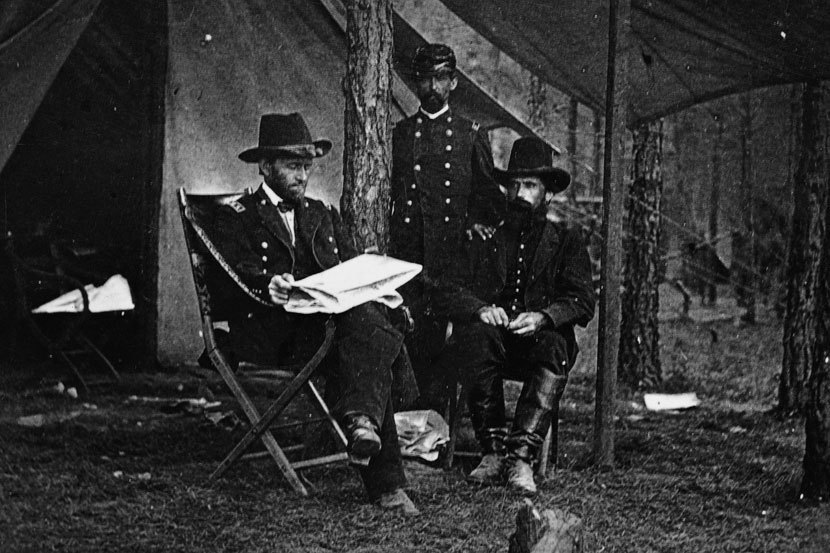

LOA: What do they tell us about Grant and war?

Schilling: That he was good at waging it, but he didn’t enjoy it. Robert E. Lee is reported to have said at the battle of Fredericksburg that “It is well that war is so terrible—we should grow too fond of it.” It’s nearly impossible to read these letters and imagine Grant expressing similar sentiments. He’s too aware of the human cost of war, and not simply in terms of the loss of life on his own side. “Some of the volunteers,” he writes from Mexico in 1846, “seem to think it perfectly right to impose upon the people of a conquered City to any extent, and even to murder them where the act can be covered by the dark. And how much they seem to enjoy acts of violence too!” From Tennessee, shortly after the fall of Fort Donelson in 1862: “These terrible battles are very good things to read about for persons who loose no friends but I am decidedly in favor of having as little of it as possible.” And then from Spotsylvania in 1864, nine days into the Wilderness Campaign: “The world has never seen so bloody or so protracted a battle as the one being fought and I hope never will again.” Grant was a patriot who was proud of serving his country at arms, but he had no illusions about the essential grimness of his chosen trade.

LOA: Do you have a favorite letter in the collection?

Schilling: Not being as decisive as Grant, I’ll name two. One is the letter Grant writes on May 11, 1846, after his first two battles in Mexico. “There is no great sport in having bullets flying about one in evry direction,” he observes, “but I find they have less horror when among them than when in anticipation.” Grant has “seen the elephant” and learned that he can lead his men under fire.

The other is the letter of April 25, 1865, written from North Carolina, where Grant had gone to arrange surrender terms for Joe Johnston’s army. “Raleigh is a very beautiful place,” he writes. “The grounds are large and filled with the most beautiful spreading oaks I ever saw. Nothing has been destroyed and the people are anxious to see peace restored so that further devastation need not take place in the country. The suffering that must exist in the South the next year, even with the war ending now, will be beyond conception. People who talk now of further retalliation and punishment, except of the political leaders, either do not conceive of the suffering endured already or they are heartless and unfeeling and wish to stay at home, out of danger, whilst the punishment is being inflicted.”

There is something wonderfully peaceful about the image of Grant admiring the oaks, free after four years to contemplate something other than war. There’s also our melancholy knowledge that for the next twelve years, first as commanding general of the army and then as president, Grant will struggle with the war’s unresolved legacy, a struggle that continues to this day.