For more than sixty years, two real people have been hiding in plain sight near the end of one of the most famous novels of the twentieth century. In Chapter 33 of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), narrator Humbert Humbert offers the following cryptic aside:

(Had I done to Dolly [Lolita], perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?)

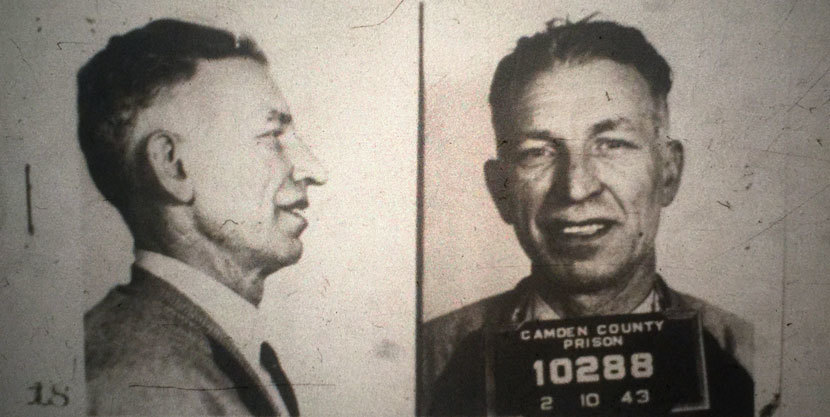

Given the dense web of allusion Humbert and his creator have already spun by then, many readers may simply take passing note of these names and move on, swept along by the novel’s headlong momentum. In the decades following Lolita’s publication, only a handful of journalists and critics tried to connect Humbert’s parenthetical query to a real-life crime: the abduction of eleven-year-old New Jersey resident Sally Horner by a serial pedophile named Frank La Salle, who spirited her across the United States and, passing himself off as her father, held her captive for nearly two years before police caught up with him—and finally liberated Horner—in San Jose, California, in March, 1950.

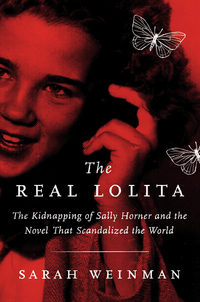

In her new book The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World (Ecco), Sarah Weinman draws on firsthand interviews and extensive research into public records to reconstruct the Sally Horner case in greater depth than anyone has ever done before. She also argues, persuasively, that press coverage of the crime served as a critical inspiration for Nabokov, giving him a kind of narrative ballast that he needed to jump-start his novel, the seeds of which had been germinating in his imagination for years.

An authority in the fields of both crime fiction and true crime, Weinman confidently weaves together two parallel narratives: one set in a seamy world of bus stations, trailer parks, and what used to be known as “broken homes,” the other in a high-literary milieu of elite New York publishing circles and the Ivy League schools where Nabokov taught literature. With equal vividness she captures the aristocratic émigré author, writing his masterpiece in motels around the country during his summer breaks from teaching, and the resilient young girl whose real-life story —tragically cut short by a car accident in 1954—has been overshadowed by her fictional counterpart, until now.

Sarah Weinman edited the two-volume anthology Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s & 50s for Library of America in 2015. Via email, she answered our questions about The Real Lolita.

Library of America: The Real Lolita grew out of a feature article you wrote for the online magazine Hazlitt in 2014. What led you to Sally Horner in the first place, and why has it taken so long for her story to come to light?

Sarah Weinman: It was, I believe, late in 2013, and late at night, as is my wont, I was looking up obscure crime stories on the Internet. (Wikipedia has proven quite useful to me, before and since, but also message boards, missing persons databases, and the like.) I’d recently finished writing and reporting a story about a man serving a life sentence for murder who had won a private detective novel contest—that piece appeared in the New York Times Magazine in early 2014—and I was casting around for my next idea. I somehow found myself reading Alexander Dolinin’s 2005 TLS essay connecting the Sally Horner kidnapping to Lolita, and while I know I had read that piece before, this time it stuck. And this time, I wondered, had anyone reported out what happened to Sally in full?

I realized right away that no one, in fact, had, so I set out to do it. As to why it’s taken so long: maybe because no one dug deep into shoe-leather reporting, only relying only on surface connections (Dolinin, and also, decades earlier, Pete Welding in the November 1963 piece for Nugget that the Nabokovs slapped down by letter). There aren’t many people who are well-versed in both the literary world and in the crime reporting world, so here was a story tailor-made for my obsessions and interests. Would that we could all be so lucky in the stories we find and the ones we tell.

LOA: As you indicate, for years after the publication of Lolita both Vladimir Nabokov and his wife Vera took pains to disavow any real-life inspiration for his work. Yet the fact remains that Sally Horner and Frank La Salle are cited by name right there in the text. Do you care to speculate as to Nabokov’s possible motivation for inserting that parenthetical aside?

Weinman: I keep coming back to the idea of game-playing, but also of blurring the line between reality and fiction. Lolita, after all, starts with “John Ray, Jr.” presenting Humbert Humbert as a case study with faux seriousness, before ceding the stage to HH’s dazzling, manipulative, seductive storytelling. And since parentheticals are where Humbert revealed the truth he was trying to hide in the text, it follows that putting Sally’s story in parenthesis, even as a throwaway, is more like a flashing neon sign, if you look at it the right way (perhaps with infrared glasses). What’s clear is that it was deliberate, that Nabokov meant the reader to make the connection. But calling him out on that connection? Well, that might not go over so well, as Pete Welding (and Al Levin?) found out. . .

LOA: Is there any evidence to suggest Nabokov ever came to regret having included that passage in the book?

Weinman: None that I could find, and I doubt strongly he did regret it. That said, I found it curious there wasn’t a single shred of reference to Sally’s plight in his archives beyond that one notecard. Considering how meticulous the Nabokovs were about keeping every piece of Lolita-related ephemera (Zsa Zsa Gabor dressed as Lolita for Cosmopolitan? Really?!), the lack of anything to do with Sally Horner stood out. Absence can tell as much as inclusion, and The Real Lolita is as much about what I couldn’t find as what I could.

| Read Lolita in |

|

| Vladimir Nabokov: Novels 1955–1962 |

LOA: In your conclusion you note that for sixty years Lolita has often been misconstrued as something much more racy and even lighthearted than it really is. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, are we more likely to focus on what Vera Nabokov hoped readers would take away from the novel—“the child’s helplessness, her pathetic dependence on the monstrous HH, and her heartrending courage all along?”

Weinman: I really hope we can. Lolita has been dubbed a love story, a comedy, a madcap adventure, and those are the tools Nabokov used to ensorcel the reader into Humbert Humbert’s skewed viewpoint. But underneath these trappings is a real horror story. A crime story (there’s murder and rape and violence, so how could it not be a crime story, even though Nabokov had, at best, a deeply ambivalent relationship with genre, and more often an adversarial one?). A tragedy about a young girl robbed of a chance to grow up. I’m speaking of the fictional Dolores Haze, but of course I’m also speaking about Sally Horner, too long hidden in shadow by her fictional avatar.

LOA: Given your familiarity with such a range of both crime fiction and true crime writing, we’re curious to get your opinion on the following declaration: “You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style.” (Granted, it comes from a notoriously unreliable source. . .)

Weinman: Clearly it’s meant as irony, a joke (which also foreshadows HH’s later reckoning with what he has done to Dolores, that if there wasn’t love or meaning then “life is a joke”). And of course Humbert’s style is in marked contrast to Frank La Salle, whose prose style was the antithesis of fancy, bordering on crude and delusional. But of course, delusions don’t have to be crude. They can be fancy and well-written. Monsters lurk everywhere, in all sorts of erudite disguises. It is human nature to be fooled by these people; how else to explain, for example, the trope of serial killers being “such nice guys?”

But it is important to remember how unreliable Humbert Humbert’s narration is. I keep thinking about the scene in the Enchanted Hunters, his description of his “deflowering” (obviously, rape) of Dolores. That she initiated. That she wasn’t a virgin, so it’s okay. But of course, we only have his word. And why should we trust it?