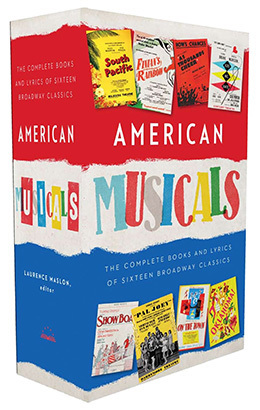

Laurence Maslon is the editor of the Library of America collection American Musicals (1927-1969): The Complete Books and Lyrics of Sixteen Broadway Classics and the author of Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America, to be published this fall by Oxford University Press. Prompted by the current revival of My Fair Lady (one of the sixteen works included in the American Musicals collection), which is expected to be a serious contender in this week’s Tony Awards, he offers the following guest post on the genesis of My Fair Lady and its enduring appeal.

This spring, more than a century after her first presentation, Eliza Doolittle will once again be invited to the ball.

On June 10, when the 72nd Annual Tony Awards are presented at Radio City Music Hall, Lincoln Center Theater’s elegant revival of Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe’s My Fair Lady will swan down the proverbial staircase to the tune of ten nominations. (The original 1956 Broadway production was nominated for ten awards— there were fewer categories then—and won six, including Best Musical.) Every generation or so, the musical version of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion comes back to town to remind theatergoers how seductive it can be to revel in an evening of theatrical sophistication.

| Read My Fair Lady in |

|

| American Musicals: The Complete Books and Lyrics of 16 Broadway Classics (Two volumes) |

When I was preparing Library of America’s two-volume collection of classic musicals from Broadway’s Golden Age, there were only two provisional assumptions: we had to include something by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and we had to include My Fair Lady. The show’s contribution to the elevation and evolution of the narrative musical form; its artful appropriation of a revered literary masterpiece; and its intoxicating popularity around the world made My Fair Lady a cultural milestone of the late 1950s—and in ways that are still resonant today.

Like all great game-changers, its creation was anything but inevitable. Lerner and Loewe were among several Broadway songwriting teams that emerged after World War II, immensely influenced by the changes that Rodgers and Hammerstein had wrought in the musical form. The composer, Loewe, a German émigré with an Austrian background who had studied piano with Kurt Weill’s teacher, was seventeen years Lerner’s senior. Lerner—the words man—was the son of New York Jewish privilege, educated at Choate and Harvard, an obsessive-compulsive go-getter with an addiction to serial monogamy. He prided himself on his literary tastes and was particularly obsessed with cracking open Shaw’s social comedy for the musical stage.

It would be a mighty challenge. Pygmalion, written in 1912, was a popular success in its day, playing around the world. It had been made into a well-regarded 1938 film (for which Shaw received an Academy Award for his screenplay) and, with its whacking great leading roles, consistently revived on Broadway. A pioneering Socialist, Shaw was far more concerned with breaking down the arbitrary boundaries of the British class system than he was in writing a romantic lark, but to his continued vexation, from the moment the play opened, audiences wanted the misogynistic Professor Higgins to renounce his ways and run off at the final curtain with the transformed flower girl, Eliza Doolittle. There is immense passion in Pygmalion, but only for social equality, not between its leading characters.

The romantic conventions of the mid-century American musical—along with its nearly obligatory promotion of a good time—offered considerable obstacles. Lerner decided that fidelity to his beloved source material might provide the answer: “There was enough variety in the moods of the characters Shaw created,” he wrote, “and we could do Pygmalion simply by doing Pygmalion and adding the action that took place between the acts of the play.” It was a liberating approach and, to this day, provides a model for “opening up” source material for a musical adaptation. At heart, Lerner also knew the show contained that ageless musical comedy scenario—a Cinderella story. No one in the audience could be immune to the sight of the transformed Eliza, dressed to the nines, a Cockney girl about to take her place among dukes and duchesses at the Embassy Ball.

Allied with one of the most impressive creative teams in Broadway history—director Moss Hart, leading players Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews (barely out of her teens), and costume designer Cecil Beaton—Lerner and Loewe polished and perfected their jewel of a show through some stormy tryouts (literally—there was a blizzard opening night in New Haven) in the spring of 1956. Two things in particular were problematic: Harrison’s self-indulgent egotism and the title, which was wearily agreed upon only because posters had to be printed (it was called London Bridge early on). Expectation ran absurdly high when My Fair Lady, trimmed and refined, opened at the Mark Hellinger Theatre on March 15, 1956. The next morning’s papers left no doubt about it; Walter Kerr in the Herald-Tribune told his readers to stop reading his review and immediately write away for tickets. The show became a hit of unprecedented proportions, running for more than six years—2,717 performances—breaking all previous records. Oklahoma! might have been the musical theater’s first phenomenon, but My Fair Lady was its first blockbuster.

Its reflected glory reached into practically every corner of popular culture. Columbia Records had put up almost $400,000—the show’s entire original investment—in order to procure the recording rights. The original Broadway production’s cast album was far and away the most successful album of its time—in any and every category; it stayed on the pop album charts (which only went as low as Number 50 back then) for 480 weeks—nearly a decade. Only two albums of any genre released since then have surpassed that. Selections from My Fair Lady (as well as its creators) appeared frequently on The Ed Sullivan Show, and pop crooners had Number One singles from the score. It was the basis of the first musical parody in MAD magazine history: “My Fair Ad-Man,” a spoof of Madison Avenue.

It was also immensely influential, with consequences that still affect the artistry of the musical theater. Rex Harrison was famously (or infamously) a non-singer and his musical debut changed producers’ perceptions about what kind of actor could front a musical. Within slightly more than a decade, Richard Burton, José Ferrer, Robert Ryan, Vivien Leigh, Melina Mercouri, Katharine Hepburn and Lauren Bacall were given starring roles in Broadway musicals—a phenomenon that continues: witness Daniel Radcliffe, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and David Hyde Pierce in recent musical outings. The very improbability of the Shavian source material proved more of an incentive than a warning. The next twenty years would see musical adaptations of the most improbable literary masterpieces: Sherlock Holmes, Pride and Prejudice, A Tale of Two Cities, Elmer Gantry, the New Testament—often with predictably risible results.

What My Fair Lady did most of all, back in the day, was to restore some lost continental glamour to the New York stage for the first time in three decades; the sensible Republican cloth-coated years of the Eisenhower administration were temporarily transformed into a silk-clad high society fantasy. It tapped into our ongoing obsession with British culture and manners, something that—from the popularity of Downton Abbey, The Crown, and the Royal Wedding—seems to be waxing rather than waning. In 1974, when our colony, er, country, was in the doldrums and fraught with political and cultural incivility, a documentary came out that provided countless clips of all those relentlessly cheerfully uncomplicated movie musicals that My Fair Lady worked so hard to obviate. The ad campaign for That’s Entertainment had the tagline: “Boy. Do We Need It Now.”

Civility, grace, manners—by George, do we need it now.