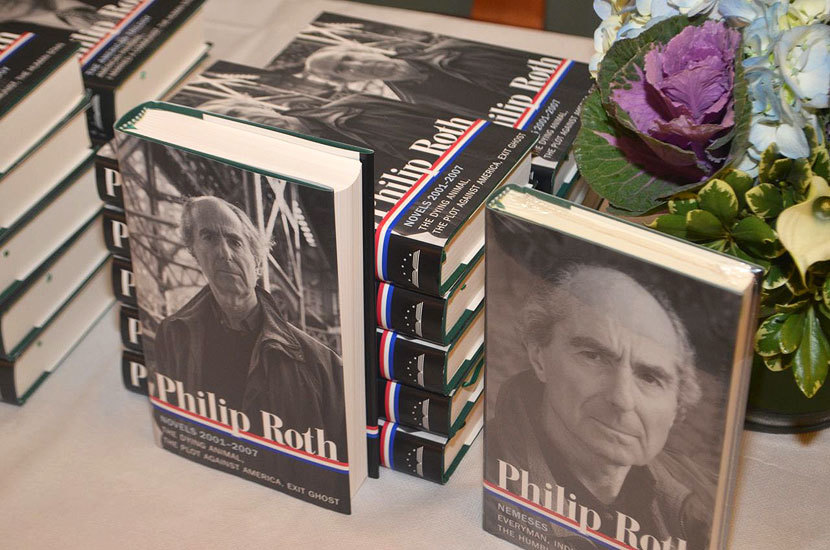

Novelist Philip Roth died on May 22 at the age of 85. In 2005, he became the third living writer to be published in the Library of America series, after Eudora Welty in 1998 and Saul Bellow in 2003. In total, Library of America publishes ten volumes of Roth’s collected works; the final volume, Why Write? Collected Nonfiction 1960–2013 was issued last fall.

Library of America President and Publisher Max Rudin reflects on his friendship and collaboration with Roth here. Below, in alphabetical order, a distinguished group of writers and critics offer their remembrances.

Megan Abbott • Blake Bailey • Harold Bloom • Joshua Cohen • Jonathan Lethem • Joyce Carol Oates • Elaine Showalter • Sean Wilentz

Megan Abbott

“The end is so immense, it is its own poetry,” says one of Roth’s characters in Exit Ghost. “It requires little rhetoric. Just state it plainly.”

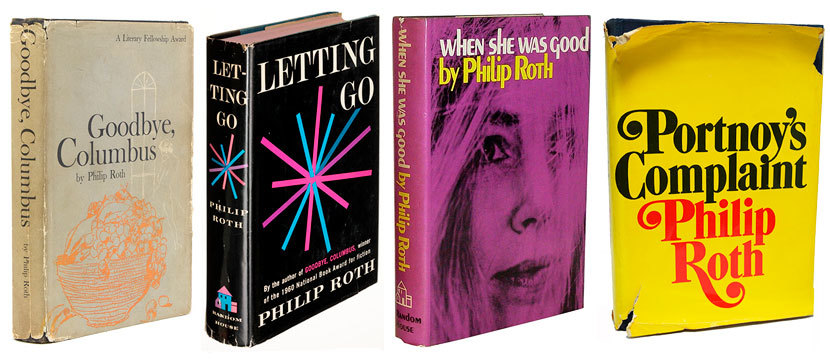

But it is so hard to do. I can’t remember a time when Philip Roth’s books weren’t in my life. As a kid, I remember running my fingers over the spines of my parents’ copies of When She Was Good, Portnoy’s Complaint, and Goodbye, Columbus. I could sense how important and grownup they were by how my parents talked about them. Peeking at a few pages, I felt like I was peering into an adult world that seemed exotic, complicated, intricate—a world I wanted into. When I began reading him in earnest as a teenager, it felt like my brain cracked open. Here, unlocked, were all the infinite secrets of men, women, human nature, family, identity, loss. Some of them I understood intuitively even then, but I could also sense that I’d need to keep returning to these books because there were even deeper secrets, greater truths to be had. Life hadn’t knocked me around that much yet, and I haven’t knocked myself around too much, but it would, and the books would change, take on new nuances and ambiguities, as if by magic. Roth’s incantational hand.

Now it’s been a lifetime of reading Roth, and re-reading Roth. Reading him with my family, with close friends, with students, and reading alone and greedily when each new book came out. It’s been a project both intellectual and emotional, both urgent and neverending. I return to him as one returns to the great loves of one’s life—with longing, with hunger, and with the heightened understanding that comes from experience. Because the more you live and lose and fail, the more Roth reveals himself to you. These are books that are not merely alive, they’re living. A long row on my bookshelf weighty with ideas and conflict and heart and loss. Thank god, we have them still.

Back to top

Blake Bailey

I didn’t know what to expect the first time I visited Philip Roth at his apartment on the Upper West Side. I was between books, and had dropped him a note asking whether he might consider letting me be his biographer. (I’d heard a rumor that he and my predecessor, Ross Miller, had parted ways.) He asked me to stop by the next time I was in town and we’d talk. “He’s shorter than I expected” were the words that appeared in the little thought-bubble above my head when he opened the door for me that first time. (As I later learned, he’d lost three inches of height because of a deteriorating spine.) We sat down and chatted: he remembered his old friend Cheever (a previous biographical subject of mine) with humorous fondness, and told me that he was collaborating on an email novel—the only fiction he was willing to write in retirement—with the adored eight-year-old daughter, Amelia, of a good friend. I mentioned that I too had an eight-year-old daughter named Amelia; it seemed a good augury. After a delightful if inconsequential hour or so, he asked me to come back in a couple days and we’d talk some more. “How’s your back feeling?” I solicitously inquired as he opened the door for me that second time. “You’re not here to talk about my back,” he said, and motioned for me to sit down. Then he put on a large, lopsided pair of glasses and reached for a legal pad. This, I realized, was the job interview. First question: “Why should a gentile from Oklahoma write the biography of Philip Roth?” Silence. We looked at each other. “Well,” I said at last, “I’m not a bisexual alcoholic with an ancient Puritan lineage, but I wrote a biography of John Cheever.” Three or four hours later, I was hired.

Back to top

Harold Bloom

Philip Roth’s departure is a dark day for me and for many others. His two greatest novels, American Pastoral and Sabbath’s Theater, have a controlled frenzy, a high imaginative ferocity, and a deep perception of America in the days of its decline. The Zuckerman tetralogy remains fully alive and relevant, and I should mention too the extraordinary invention of Operation Shylock, the astonishing achievement of The Counterlife, and the pungency of The Plot Against America. His My Life as a Man still haunts me. In one sense Philip Roth is the culmination of the unsolved riddle of Jewish literature in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The complex influences of Kafka and Freud and the malaise of American Jewish life produced in Philip a new kind of synthesis. Pynchon aside, he must be estimated as the major American novelist since Faulkner.

Back to top

Joshua Cohen

I can’t think of any writer in any language, in any era, who thought more about his own death. And who, in a sense, wrote almost all of his work as preparation for it. How, then, to mourn the great mourner? How to give Roth his due without becoming a character he’d travesty? These are questions to be answered not a few days after his passing, but for years, for decades, in books by writers of the future. For now, peace to Newark. Peace to Weequahic.

Back to top

Jonathan Lethem

I only ever made Philip Roth laugh twice, to my knowledge. That’s weak recompense for the thousand hilarities Roth’s bestowed on me—bitter snorts of recognition, giggles of astonishment at narrative derring-do, sheer earthy guffaws. . . . The second time I made Roth laugh is more important to me: we stood together in the late stages of an Upper West Side brunch party, where I dandled my infant son while Roth looked on quite reasonably impatient to be elsewhere. In a quiet panic, bobbing up and down to soothe the six-month-old, I found myself monologuing to Roth’s increasingly arched eyebrows. Finally, straining for a reference that would interest my hero, I turned the boy’s head slightly to the side, displaying the fat curve of his cheek, and said, “It resembles one of those disembodied unshaven cigar-smoking heads in a Philip Guston painting, don’t you think?” The juxtaposition of my pink son and the grotesques of Guston . . . did the trick. And this was another lesson from Roth: In putting across what wants putting across, in seeking a rise from a listener, do whatever it takes, grab any advantage, even employ the baby in your arms. I would have juggled that baby if it would have helped.

―From Philip Roth at 80: A Celebration

Back to top

Joyce Carol Oates

Philip Roth was a slightly older contemporary of mine. We had come of age in more or less the same repressive 1950s era in America—formalist, ironic, “Jamesian,” a time of literary indirection and understatement, above all impersonality—as the high priest T. S. Eliot had preached: “Poetry is an escape from self.” Boldly, brilliantly, at times furiously, and with an unsparing sense of the ridiculous, Philip repudiated all that. He did revere Kafka—but Lenny Bruce as well. (In fact, the essential Roth is just that anomaly: Kafka riotously interpreted by Lenny Bruce.) But there was much more to Philip than furious rebellion, for at heart he was a true moralist, fired to root out hypocrisy and mendacity, in public life as well as in private life. Few saw The Plot Against America as actual prophecy, but here we are.

He will abide.

(Also posted at The Guardian)

Back to top

Elaine Showalter

“Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion. All one’s concentration and flamboyance and originality reserved for the grueling, exalted, transcendent calling. I looked around and I thought, This is how I will live.” In The Ghost Writer, Roth, writing through the persona of the young novelist Nathan Zuckerman, imagined a vocation as an artist, with all its costs and comic ironies, and committed himself to it. At the same time he acknowledged that however idealistic the choice might be, the writer he would become was neither nice nor polite. In his fiction, he was “ a different person.” Roth’s ambition and literary career was on a colossal scale, and he remained true to his calling. I don’t think we will see his like again. His fiction is haunted by ghosts of other writers, other possible lives, historical figures, alternative selves. Now he will become a ghost writer himself, a great figure, not nice or polite, often outrageous, imperfect; but a writer for the ages, an inspiration for young men and women writers and a universe of readers.

Back to top

Sean Wilentz

Philip Roth was, first, a novelist, but he was also an American historian who comprehended that vocation long after he’d heard it. I’m not sure when he got the call, but no later than The Great American Novel, its Port Ruppert Mundys a fantasy of a real ball club, the Cleveland Spiders, the worst of all time, and so a touchstone for Philip’s gargantuan imagination. By the time he and I became friends, amid the Clinton impeachment, he’d seized his great theme, the stream of fanatic American righteousness that from time to time bursts its banks only to be subdued in the nick of time—so far. He read American history voraciously, not simply as chronicle but as literature; although he practiced it his own way, he thoroughly understood the historian’s craft. I will miss that voracity, as I will miss our continuing intense little seminar. But right at the moment, I miss that laugh of his, the eruptions of mirth that punctuated our friendship as they punctuated his work. Boy, do we need that laugh, now more than ever.

Back to top