Two hundred and fifty years ago this month, a Pennsylvania Farmer changed the course of the British Empire.

|

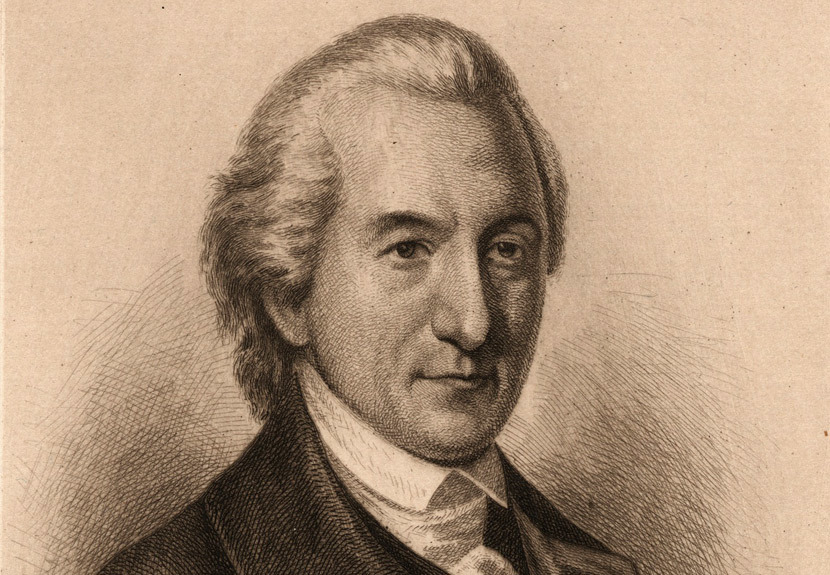

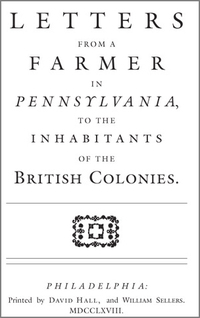

On November 30, 1767, the Pennsylvania Chronicle published the first of twelve letters from a “Pennsylvania Farmer,” the work of Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson. Completed on February 8, 1768, and later published as a pamphlet, the letters galvanized readers from Georgia to Massachusetts, helping to forge an American identity that united patriots in all of the colonies in a single cause.

*“Whoever seriously considers the matter must perceive that a dreadful stroke is aimed at the liberty of these colonies. I say of these colonies; for the cause of one is the cause of all.”

—John Dickinson, 1768*

The Context

Testifying before the British House of Commons on February 13, 1766, in an attempt to clarify for Parliament the American perspective on the administrative crisis then roiling the British Empire in North America, Benjamin Franklin had drawn a distinction between “internal” taxes, such as the stamp taxes, and “external” taxes, such as duties levied on imports. Franklin seemed to suggest that Americans would tolerate the latter, and history appeared to bear him out. The British government seized on the opening Franklin provided. In 1767 the chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend, observed that “since the Americans were pleased to make that distinction,” he was “willing to indulge them.” Consequently, Parliament went on to levy “external” taxes or duties on colonial imports of lead, glass, paper, and tea, the revenue from which was to be applied to the salaries of royal officials in the colonies, thereby affording them a measure of independence from the colonial assemblies, their traditional paymasters.

It fell to John Dickinson, a wealthy and influential lawyer and former member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, to clarify American thinking about Parliament’s rightful authority. To do so, he assumed the guise of a humble farmer, freed from the busy scenes of life by virtue of income from interest on money out on loan—a posture designed to establish his disinterestedness for the reader. Like nearly all colonists, Dickinson conceded that Parliament had the right to regulate America’s trade, but insisted that it had no right whatsoever to impose taxes on the colonies, whether internal or external, with the aim of raising money. But how to distinguish between duties designed to regulate trade and duties designed to secure revenue? The answer, said Dickinson, lay in the colonists’ ability “to discover the intentions of those who rule over them.” Suddenly, Americans had turned the imperial debate into an elaborate exercise in the deciphering of British motives—and this at a time when dissembling and deceit were thought to be everywhere in Anglo-American culture. No wonder that Americans in these years became obsessed with British conspiracies designed to deprive them of their liberties.

The Response

Within a month of their appearance in the Pennsylvania Chronicle, nineteen of the twenty-three English-language newspapers in the colonies reprinted some or all of the Farmer’s letters. A Philadelphia publisher soon collected them in a closely printed, seventy-one page pamphlet released in March, with a second edition following a month later. More editions soon appeared in Boston, New York, London, Dublin, and, in French, in Amsterdam.

Everywhere the response was electric. The first two of the Farmer’s Letters were published in Boston on December 21, 1767, and on the following day the Boston town meeting, James Otis presiding, instructed its delegates to the Massachusetts House of Representatives to put forward a petition to the King for repeal of the Townshend Acts. The Massachusetts legislature did the town meeting one better, when on February 11, 1768, under the leadership of Samuel Adams, it addressed a Circular Letter to the other colonial assemblies denouncing the new duties as a violation of the principle of no taxation without representation, even as it admitted that “His Majesty’s high Court of Parliament is the supreme legislative power over the whole Empire.”

On February 28, 1768, Massachusetts Governor Francis Bernard forwarded a complete set of the Farmer’s Letters to Richard Jackson, a Member of Parliament who had formerly served as Massachusetts’s colonial agent in London. He warned that if the “System of American Policy,” advanced in the Letters, “artfully wrote and . . . universally circulated, should receive no Refutation . . . it will become a Bill of Rights in the Opinion of the Americans.”

In London, the reactions were not long in coming. In a March 13, 1768, letter to his son William Temple Franklin, Benjamin Franklin recounted a recent meeting with Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the Colonies, who “mentioned the Farmer’s letters to me, said he had read them, that they were well written, and he believed he could guess who was the author, looking in my face as the same time as if he thought it was me. He censured the doctrines as extremely wild.” The Monthly Review (July 1768), a Whig journal, found the Letters to be “a calm yet full inquiry into the right of the British parliament, lately assumed, to tax the American colonies; the unconstitutional nature of which attempt is maintained in a well-connected chain of close and manly reasoning.” It concluded that “if reason is to decide between us and our colonies, in the affairs here controverted, our Author, whose name the advertisements inform us is Dickenson (of Pennsylvania), will not perhaps easily meet with a satisfactory refutation.”

Dickinson’s authorship was indeed soon widely known, and when a third edition of the Letters was published in Philadelphia in the autumn of 1768, some copies featured an engraved portrait of Dickinson. An edition published by William Rind in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1769 paired the Farmer’s Letters with another series, called the Monitor’s Letters, by Arthur Lee, and introduced the combined edition with a preface attributed to Lee’s brother Richard Henry Lee. It reads in part:

Whoever considers again that the nature of men in authority is inclined rather to commit two errors than to retract one (see Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion), will not be surprised to see the Stamp-Act followed by a Bill of Right, declaring the power of Parliament to bind us in all cafes whatsoever; and this act followed again by another, imposing a duty on paper, paint, glass, etc. imported into these colonies. But however unbounded may be the wish of power to extend itself, however unwilling it may be to acknowledge mistakes, ‘tis surely the duty of every wise and worthy American, who at once wishes the prosperity of the Mother country and the colonies, to point out all invasions of the public liberty, and to shew the proper methods of obtaining redress. This has been done by the Authors of the following LETTERS with a force and spirit becoming freemen, English freemen, contending for our just and legal possession of property and freedom. A possession that has its foundation on the clearest principles of the law of nature, the most evident declarations of the English constitution, the plainest contract made between the Crown and our forefathers, and all these sealed and sanctified by the usage of near two hundred years. American rights thus resting on the best and strongest ground, it behoves all her inhabitants with united heads, hearts, and hands, to guard the sacred deposit committed by their fathers to their care, as well to bless posterity as to secure the happiness of the present generation.

Not until the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776 would a single pamphlet exercise such a dramatic influence on the course of the American Revolution.

The full text of Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, complete with detailed annotations by historian Gordon S. Wood, can be found in The American Revolution: Writings from the Pamphlet Debate, 1764‒1772.