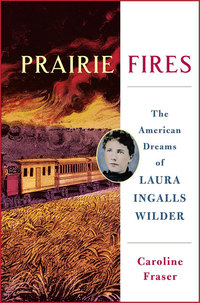

Out today from Metropolitan Books, Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser is billed as the “first comprehensive historical biography” of the author of the beloved Little House books.

Fraser is the editor of Library of America’s two-volume edition of Wilder’s Little House series, which has won praise for presenting the nine novels—shorn of the Garth Williams illustrations that accompanied earlier editions meant for children and with detailed end notes—as “literature worthy of adult readers.” In her new book, Fraser draws on unpublished manuscripts, correspondence, journals, and other material to present an unvarnished look at Wilder’s life story, the hardscrabble frontier milieu that shaped her, and how she transmuted the experiences of her early years into enduring fictional art.

Below, we’re pleased to present the following excerpt from Fraser’s introduction to Prairie Fires.

By Caroline Fraser

As children, we thought we knew her. She was the real-life pioneer girl who survived wildfires, tornadoes, malaria, blizzards, and near-starvation on the Great Plains in the late 1800s. She was the fierce, uncompromising tomboy who grew up to write famous books about her life: Little House in the Big Woods, Farmer Boy, Little House on the Prairie, On the Banks of Plum Creek, By the Shores of Silver Lake, The Long Winter, Little Town on the Prairie, and These Happy Golden Years. She was the woman whose true-life stories went on to sell over sixty million copies in forty-five languages and were reincarnated in the 1970s and 1980s as one of the longest-running, most popular shows in television history, still in syndication.

But as adults, we have come to see that her autobiographical novels were not only fictionalized but brilliantly edited, in a profound act of American myth-making and self-transformation. As unpublished manuscripts, letters, and documents have come to light, we have begun to apprehend the scope of her life, a story that needs to be fully told, in its historical context, as she lived it. That tale is different from the one she wrote. It is an adult story of poverty, struggle, and reinvention—a great American drama in three acts.

The third act was a long time in coming. At fifty-seven, Wilder was still far from becoming the emblematic figure of pioneer history. The woman whose life would become synonymous with the settlement of the West had spent most of her adult life living in the American South. She was not yet famous, had not yet written a book; the only writing she had published was her farm paper column. Anxious, she suffered from nerves and had a recurrent nightmare of walking down a “long, dark road” into obscure woods, the path of poverty.

She prided herself on superior hen-raising skills and keeping an immaculate house. She worried about whether giving women the vote might lead to moral laxity. A product of rural life, she also stood outside it, questioning the iron drudgery of turn-of-the-century domestic expectations. She advised women to give up the exhausting ritual of spring cleaning.

She had a sharp temper and a dry humor, noting the resemblance of a yard full of swine to their owners. Judgmental of others, she could be humble, even self-excoriating. She was parsimonious to a fault, but when she went into town she dressed elegantly in full skirts, lace collars, and hats garlanded with feathers or flowers. She favored long, dangling earrings, fastening her blouses with a cameo brooch. She loved velvet.

She was not an intellectual, but she had an intellect. She had never graduated from high school, but had studied with passion and vigor the Independent Fifth Reader. She knew a song for every occasion and passages of Shakespeare, Longfellow, Tennyson, Scott, Swinburne, and the Brownings. Books took pride of place in her living room, on custom- built shelves beside a prized stone hearth.

As her fifties drew to a close, she stood at a turning point. The first act of her life was long over. Her childhood had been packed with drama and incident: Indian encounters, prairie fires, blizzards, a virtual compendium of American frontier life. Growing up, she could count her possessions on her fingers. One tin cup. One slate, for school. One hair ribbon. A doll her mother made her. Clothes and shoes were hand-me- downs: a good dress for Sundays, another for all the other days. She married at eighteen and was a mother a year later.

By the age of twenty-one, she knew that everything she had ever had, no matter how hard-won, held the capacity to be lost. After a series of disasters, she and her husband left the Dakotas to rebuild seven hundred miles south, a long climb out of poverty constituting her life’s second act. She took in boarders and waited on tables. Her husband, crippled by a stroke in his twenties, recovered enough to drive a wagon, delivering fuel and freight. Their daughter, Rose, left home when still a teenager, eventually becoming a celebrity biographer in San Francisco. As soon as she saw the easy money to be made selling inspirational life stories of men as self-made as she was—Henry Ford, Jack London, Herbert Hoover—she began urging her mother to join her in the writing trade.

Wilder would become one of the self-made Americans her daughter so admired. In the third act of her life, in the midst of the Great Depression, she began recording, in soft pencil on tablets from the dime store, a memoir of her youth, the story of homesteaders who had unwittingly caused the Dust Bowl she was living through. Painfully casting her mind back to the previous century, she pressed on, kept awake all night by remembering her family’s misfortunes and failed crops, her sister falling ill and going blind. What had been punishing to survive was heartbreaking to relive. “It’s H—,” she wrote to her daughter, taught never to swear.

Rose once jotted down a quotation she attributed to her mother: “I don’t know which is more heartbreaking, a dream un[ful]filled or a dream realized.” She would help her mother realize a dream, bringing her professional connections and polish to the work, adding touches of cozy security to the hard reality. But it was her mother’s stoic vision of pioneer grit that prevailed.

Wilder’s perseverance gave rise to one of the most astonishing rags-to-riches stories in American letters. On the brink of old age, fearing the loss of everything in the Depression, Wilder reimagined her frontier childhood as epic and uplifting. Her gently triumphal revision of homesteading would convince generations that the American farm was a model of self-sufficiency. At the same time, it would hint at the complex realities behind homesteading, suggesting that it broke more lives than it sustained.

Living most of her life in poverty, Wilder survived long enough to become a wealthy woman, a legend in children’s literature, and a treasured incarnation of American tenacity. But fame obscures as it reveals. Swamped in pious sentimentality, dimmed and blurred by the marketing of the myth, Wilder has become a caricature, a brand, a commodity. In addition to the hit television show, the Little House series has given rise to scores of adaptations in print, on stage, and on screen— including a Japanese anime version—and a welter of songbooks, cookbooks, sequels, and chat sites. There are licensed dolls, clothes, fabrics, and, inevitably, sunbonnets.

The real woman was not a caricature. Her story, spanning ninety years, is broader, stranger, and darker than her books, containing whole chapters she could scarcely bear to examine. She hinted as much when she said, in a speech, “All I have told is true but it is not the whole truth.”

Excerpt from Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder copyright © 2017 by Caroline Fraser. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.