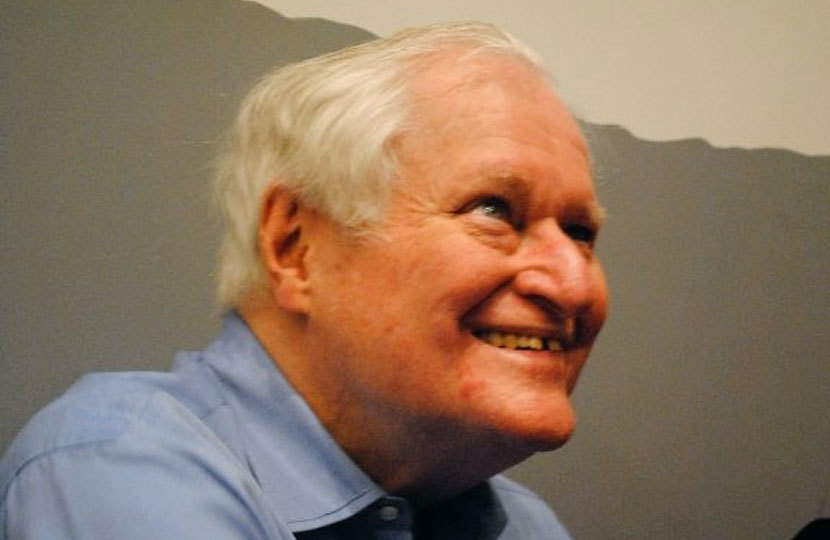

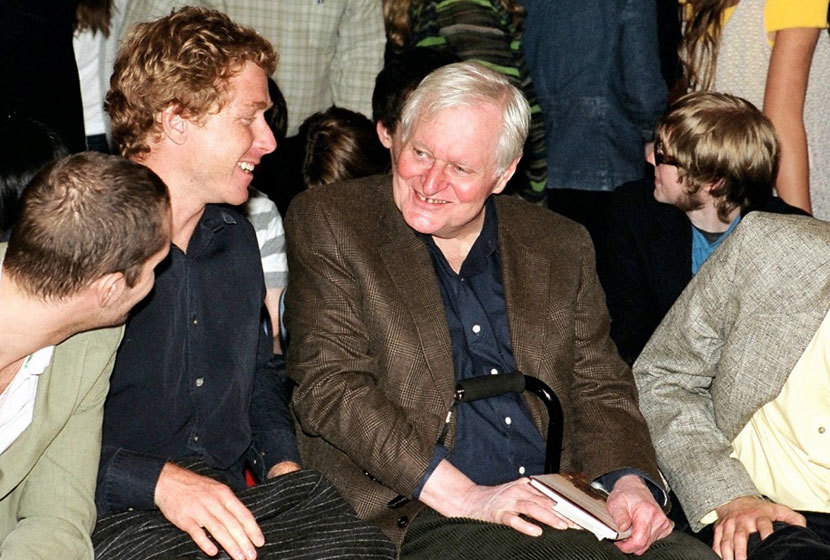

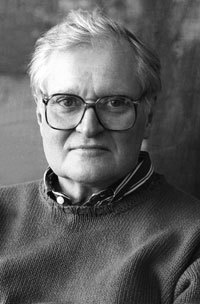

John Ashbery, who died on Sunday, September 3 at the age of 90, was the first living poet to be included in the Library of America series with the publication of John Ashbery: Collected Poems 1956–1987, in 2008. The second volume of this definitive edition of his works, Collected Poems 1991–2000, has just been published.

To celebrate Ashbery’s extraordinary legacy, Library of America reached out to a number of his fellow writers for their thoughts on the man and his work.

Charles Bernstein • Star Black • Harold Bloom • Nicholas Christopher • Marcella Durand • Adam Fitzgerald • Mark Ford • Langdon Hammer • Susan Howe • David Lehman • Eileen Myles • Charles North • Ron Padgett • Jed Perl • Marjorie Perloff • Lloyd Schwartz • Richard Sieburth • Peter Straub • Helen Vendler • Anne Waldman

Langdon Hammer

John Ashbery contained multitudes. John was the poet in my lifetime who reinvented the art form for the future while always building on the literary past, which he described once, with his customary offhand elegance, as “what Wyatt and Surrey left lying around.” Like a jogger, he was out there everyday in all weathers. He was one of us and all of us. Goodbye, great-hearted man.

Back to top

Peter Straub

I loved that John Ashbery was always so friendly and playful with me. His work changed my life—back in 1968, when I came across The Tennis Court Oath, I felt as though it had set me free. When I read him now, one of the things it makes me feel is refreshed. I am very grateful to him.

Back to top

Ron Padgett

I read John’s work in Donald Allen’s New American Poetry 1945-1960 as soon as it came out, but I didn’t “get” it until about a year later, when Kenneth Koch opened my eyes to John’s astounding gift. John quickly became a huge inspiration for me and other young poets, and the beautiful thing is that he never stopped making me feel that writing poetry is a wonderful (and normal) thing to do. We were lucky to have known him, lucky to know that he was across town writing great poem after great poem.

Back to top

Richard Sieburth

Though I barely knew him, John was always extremely generous to me. One day (perhaps two sheets to the wind?), he came over to my table at the Knickerbocker on University Place, introduced himself—we had never met before—and told me how much he admired my Hölderlin translations. You could have knocked me over with a feather (or laurel leaf). Many kindnesses followed—blurbs, letters of support. How did he find the time spread so much hospitality into so many quarters? He was always delighted that the French word “hôte” meant both host and guest, meaning that nobody ever had the upper hand. Il avait le don du don. Let his gift—his giving—be long remembered.

Back to top

Marjorie Perloff

I’ve known, loved, and admired John Ashbery for more than forty years now, but even so I wasn’t prepared for the wit and brilliance he was able to muster in an email he sent me on August 31, just three days before his death. Like so many others, I had sent him greetings on his 90th birthday, and threw in a snapshot of myself with Jeremy Irons (an actor I knew he admired) at the T. S. Eliot annual festivities in Little Gidding (UK). I had also sent him and David a little gourmet food basket. Here is the message:

Dear Marjorie,Please forgive my late reply to your email. I’m still in Hudson, and haven’t been to my beloved NYC apartment since March, 2016, and since my lovely assistant Emily doesn’t get up here that often, I’m owing a lot of letters to a lot of people, which reminds me of a line from the Firesign Theater that suddenly surfaced, “You owe a lot of money to a lot of people for a lot of airports.”

I was very impressed to see you charming the Panama hat off Jeremy Irons—you go girl!

Oh, and thank you for that incredible spread of goodies you sent for my birthday! There are still some around but I’m not sure which ones, since David doles them out sparingly. Did you ever see the movie Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? If so, you have some idea of what my life is like.

Anyway, much love and thanks, and I’ll leave space here for Baby Jane to add her personal best.

Love,

John

Who but John could have written these words? Comparing himself to Joan Crawford (Blanche), getting those starvation rations from Bette Davis (Baby Jane) in that great horror movie! On the very eve of death he was able to joke about what his “life” had become. It reminds me of one of my favorite Ashbery poems, “Houseboat Days,” where we read:

But I don’t set much stock in things

Beyond the weather and the certainties of living and dying:

The rest is optional. To praise this, blame that,

Leads one subtly away from the beginning, where

We must stay, in motion.

Staying, in motion! That’s the unique gift of Ashbery’s poetry as well as his life and it’s why he is our indispensable poet.

Back to top

Eileen Myles

John was the reigning poet in my world for the entire time I’ve been a poet in and out of New York. He remains my hero. It wasn’t so much that “he won” and he won nearly everything but that he wrote such an enormous amount of great poetry for decades, and he had a gentle subversive way of carrying it all. He wrote all kinds of poems. He showed how elastic greatness can be, how truly queer a poet is, and I don’t mean his sexuality only, he was silly, grand, abundant, hip, fuddy duddy and large. John loved dessert. I miss him in the world already.

Back to top

Nicholas Christopher

John was a great friend and a very early supporter of my work. His poems had a powerful influence on me. We shared a love of film, especially film noir, and exchanged books, tapes, and DVDs over the years. Two anecdotes. I remember John (who was a terrific art critic) commenting one day that he wondered how exactly literary criticism had set itself up as another branch of the arts—who was responsible for this “transgression,” as he put it. Second, anyone who discussed film with him knew he revered the Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, a wild compendium which purports to (and does) list the “weirdest films” of all time. I treasure the copy he gave me as a gift. I also remember fondly a story that related to his love of offbeat films and the treasures they contained: in reviewing John’s most recent book, a noted critic had gone on extensively about how the influence of Keats, Clare, and Marvell manifested themselves in a particularly significant portion of one of the poems. John found this observation enormously amusing because he said he had lifted the lines in question, nearly verbatim, from the subtitles of an Italian sci-fi sexploitation film about an army of lesbian aquanauts. A film of which this critic was apparently unaware. In short, in addition to his friendship, his loyalty, and his brilliant art, I miss his very dry sense of humor.

Back to top

Jed Perl

John was a generous man. He was never armored in his fame. When writers and artists reached out he responded. He wanted to help. He had that New York quality, that wonderful old New York quality, of being shamelessly avid for art, literature, dance, music, movies—he wanted to know everything about the old stuff and the new stuff and see how it fit together. John’s Dadaist hijinks were grounded in a classical sense of order. The crazy funny language celebrated the beauty of language and the proper use of language. He was the last of the aristocratic comedians.

Back to top

Star Black

John offered an entryway into the art world not from the outside looking in, as one views a painting in a museum, but from the inside looking out. Mostly he seemed to show up everywhere, many times with his older friends, Jane Freilicher, Kenneth Koch, Larry Rivers, always with David Kermani, and just be himself, warm, polite, deferential, slyly funny. Studying with him in the 1980s, I went from a formal undergraduate education of the English canon—Chaucer through Yeats—to checking out John Wheelwright, Laura (Riding) Jackson, Raymond Roussel, de Chirico’s surrealistic prose, and Max Ernst’s wordless collage novels, plus reading his books one after another and attending parties his friends gave for him. In recent years, I would call him in Hudson to sing him happy birthday on the telephone. He was appreciative, delighted, and patient, as usual. He then would say, under his breath, I have a masseur waiting, I would say it sounds good, he would say it is.

Back to top

Lloyd Schwartz

John Ashbery died the day before a new semester was starting. I’d been puzzling over which poems to talk to my writing students about at our first workshop. The news of his death made me think of two poems of his I especially wanted my students to see—his poignantly optimistic poem about writing, “What Is Poetry,” and the irresistibly unsettling “Worsening Situation,” which has one of my favorite Ashbery endings: “My wife/Thinks I’m in Oslo—Oslo, France, that is.” I love these poems. I love that Ashbery was kind to me when I was just starting out. I love that he loved Elizabeth Bishop, famously calling her a “writer’s writer’s writer.” And I love his classic response to the poet who came up to him after Bishop’s memorial to complain about a negative review Ashbery had written of a book of his some twenty years before: “Oh, I don’t remember that at all!”

Back to top

Charles Bernstein

One of PennSound’s most extensive author pages is for John Ashbery. The page includes dozens of audio and video recordings of Ashbery readings, starting with a 1951 Poets Theater performance of “Everyman.” We have about 100 Ashbery recordings on PennSound, including a _Close Listening radio conversation I did with John on March 18, 2016. To record the show, my son Felix and I went to see John at his Chelsea apartment. It was the last time I saw him.

John and David Kermani were deeply committed to PennSound—the largest archive of poetry recordings on the web. All PennSound recording are available free for streaming or downloading (and we have no advertising). David insisted that any place making a recording of John’s work, or digitizing an older reading, give a copy to PennSound. As a result, anyone with an internet connection can hear a comprehensive collection of Ashbery readings.

Once David and I started to work on the Ashbery PennSound page, I would meet David at the Moonstruck diner, near their apartment. After lunch, he would hand me shopping bags full of cassette tapes, videos, and CDs. Over time PennSound sorted it all out, carefully documenting each event.

John’s death is a terrible blow, just as his life was a marvelous whoosh! And his voice lives on: hypnotic, radiant, and sublime.

Back to top

Anne Waldman

I met John when I was twenty years old, still in college getting a different dose of American poethics. A more hetero model with anguished (white) men who had served in military and were “lying on mother’s bed,” “tamed by Miltown.” (What kind of drug was that?) I had been to readings by Lowell, Richard Wilbur, John Berryman, Howard Nemerov, all at experimental Bennington College, where Ezra Pound was verboten, and Gertrude Stein was considered “silly” and Williams and Stevens and Moore not much taught or “contextualized.” But I already had an alternative life in poetry through the Donald Allen anthology, little magazines, and from attending the Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965 (Ted Berrigan was holding up the New York School banner in this alien territory) and my mother’s letters to me from her Bill Berkson workshop at the New School. Frank O’Hara was unavailable to come to Berkeley, and John was living in France. We wanted John Ashbery to come home from France! The second–generation NYC school would soon be crashing in the living room of my apartment on St. Marks Place.

The line “whiter shade of pale” from Procol Harum comes to mind, now, keeps returning, since John died. I remember it was a favorite line of John’s, and I also remember that when he saw the Bob Dylan movie Renaldo and Clara some years later he was impressed with my brief appearance and moment where I say “I’d rather be home reading a good book.” John seemed oddly au courant with the pop times. A kind of hip insouciance, quick witted parlays, always kindly. Everything was fair game for his curiosity.

We moved through many of the same scenes, parties, occasions, ritualistic holidays together in the mid–sixties into the early ’70s. Flirting at a Lita Hornick party. He might have been at the party at the apartment where Kenneth Koch stripped off his shirt. Our first Angel Hair book, from the press founded with Lewis Warsh, was by Lee Harwood, love poems dedicated to John, with a Joe Brainard cover: The Man With Blue Eyes.

I had worked briefly at WRVR radio on a work-study semester at Riverside Church in 1965 where I was able to help create a few poetry shows and John recorded there. Then it was suddenly summer and Frank O’Hara had died and everyone was bereft. And the Poetry Project was born, I always felt, out of the transition of losing Frank O’Hara; out of his ashes.

It was a heady time. I was an eager child of poetry and John Ashbery was our breakthrough poet, having riveted an ever–growing number of friends, artists, readers, strangers, young poets to an elevated shift of frequency. The apocalypse had taken place with The Tennis Court Oath (1962) with its mystical dream fragments cut–ups/non sequitirs, shaped to intellect and sound: shimmering language. Also plainspoken, matter of fact, colloquial. Its title the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

Even as you lick the stamp

A brown dog lies down and dies

John’s poetry didn’t seem to own, cling to, or identify with its experience, didn’t beg on emotion and ponderous content. Things were symbols of themselves, not pointing toward weightier meaning and conclusion. “The real subject is its form,” Ashbery had said of Raymond Roussel. I remember sitting with Rivers and Mountains when it came out in 1966, on the sofa on St Mark’s Place, trembling with excitement and anticipation.

“perhaps we out to feel with more imagination”

“You were my quintuplets when I decided to leave you”

Reading John was liberating. You could take anything from the words. It was the elegant arrangement and attention of wild mind. The mind was the subject, a haven free of baggage and usual referents, you made friends with it. You didn’t know where you were going when you latched to the poems. “The Skaters” was like a dream. The surface as smooth as ice, dazzling.

And there was “A Blessing in Disguise,” which still makes me cry, a poem to read to lovers. One of the most beautiful poems in the world.

This text below is from an interview John and Kenneth Koch concocted that appeared in The World, the mimeo magazine from The Poetry Project. There’s reference to Cleanth Brooks and obsession with ambiguity. In the air with William Empson too. They were all about “ambiguity.”

John had the right take, I think. And the times were changing.

Ashbery: I was just wondering if ambiguity is what everybody is after. But in any case, why?Koch: People seem to be after it in different ways. Actually one tries to avoid the Cleanth Brooks kind, no? It seems an essential part of true ambiguity that it not seem ambiguous in any obvious way. Do you agree?

Ashbery: I don’t know. I’m still wondering why all these people want that ambiguity so much.

Koch: Have your speculations about ambiguity produced any results as yet?

Ashbery: Only this, that ambiguity seems to be the same things as happiness—or pleasant surprise, as you put it. I have a feeling that since I am assuming that from the moment that life cannot be one continual orgasm, real happiness is impossible and pleasant surprise is promoted to the front rank of the emotions. Everybody wants the biggest possible assortment of available things.

Charles North

John has meant so much to me—to American poetry—that it’s hard to know where to begin. The permissions he gave us all, enriching to this day, began with his first book, Some Trees (I still have the Xeroxed copy a friend made for me in the late 1960s when I was just beginning), continued with the undersung Tennis Court Oath (which remains a treasure chest of permissions despite being downgraded by critics, and even by John himself), and flowered in its fullest forms in Rivers and Mountains, The Double Dream of Spring, Three Poems, and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror—all, to me, among the most important books of poetry produced since the Second World War.

I was excited by a lot of poets when I began, but somehow John was my poetic hero; he still is. I remember when he was close to unknown—which was the case even in the late 1960s—apart from the few readers who noticed Donald Allen’s New American Poetry and the poets who, like me, were in their twenties and hung around The Poetry Project. It was close to impossible to believe that his reputation would extend beyond New York City, let alone that in his lifetime he would set the record for poetry awards! In his quiet—but relentless—way, he broke too many rules. He was far too self-indulgent. What he wrote didn’t sound like poetry.

I’m sure we’re all lifting a glass to John, but I’m guessing he’s free to drink with Raymond Roussel, John Wheelwright, Giorgio de Chirico, and even Henry Darger, whose names we might not know if it weren’t for John’s quietly relentless praise.

Back to top

Helen Vendler

John Ashbery taught me a new way of reading verse. I saw that I had to rise to a different wavelength—almost a mediumistic one—to tune in to his original procedures. Then it was an unusual journey through the rivers and mountains of his books. He wrote the most original prose poem of American lyric, the work paradoxically called Three Poems, which transmuted the old genre of the spiritual diary into a form of self-analysis.

Back to top

Marcella Durand

I’m thinking my experiences with John might be divided into three: the first time we met in the late 1980s; the second time we met ten years later at the Poetry Project, where, thanks to that fabled JA memory, he remembered me from the first time we met; then the third time we met, which was an interview, arranged by dear friend Olivier Brossard, for the position of assistant to John Ashbery. Which encounter was the most “important?” Of course the third, which led to five dreamlike years doing things such as following the intricacies of how John composed a sentence as he dictated letters to me. But I also think of the first: I was a clueless college student who knew that I was probably going to be a poet, but completely not finding my way in the field. I was reading a lot of Adrienne Rich and heard she was reading at a hotel in downtown New Orleans with somebody named John Ashbery. Several hours later, there I was, tremblingly holding out a copy of Selected Poems for John to sign after having my mind blown (and though I didn’t know it then, my life changed) by his reading of “The Instruction Manual.” Since that first moment, John has shown me so many ways to be a poet—not didactically, where the answers are handed to you before you even have the questions, but through his not-really-separable writing and being (and oh, how funny he was—I think I spent at least half my time working for him laughing). I already miss him so much, but also feel he is very much still here, in the poems.

Back to top

Susan Howe

“He disappeared in the dead of winter” is the first line of Auden’s great elegy “On The Death of William Butler Yeats.” It was Auden who selected Ashbery’s first book Some Trees for the Yale Younger Poets Award in 1956. “Around the Rough and Rugged Rocks the Ragged Rascal Rudely Ran.” Tell me of another poet writing in English with such an alliterative and ecstatic range of wit and courage. He disappeared at the weekend break between summer and autumn. So many tributes are flowing in via Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, the News Hour, the newspapers! I cut this quotation from the title poem of his last collection Commotion of the Birds (2016). “It’s good to be modern if you can stand it. /It’s like being left out in the rain, and coming/ to understand you were always this way: modern,” John Ashbery was the last great American Modernist poet living and writing here among us. I feel lost without him.

Back to top

Harold Bloom

Houseboat Days (1977) was Ashbery’s seventh major volume and one of the three or four best. I introduced him in 1976 at a Yale reading and was startled by first encountering “Wet Casements.” I asked him for a copy after the reading and absorbed it during the next few days:

When Eduard Raban, coming along the passage, walked into the open doorway, he saw that it was raining. It was not raining much.

—Kafka, “Wedding Preparations in the Country”

The concept is interesting: to see, as though reflected

In streaming windowpanes, the look of others through

Their own eyes. A digest of their correct impressions of

Their self-analytical attitudes overlaid by your

Ghostly transparent face. You in falbalas

Of some distant but not too distant era, the cosmetics,

The shoes perfectly pointed, drifting (how long you

Have been drifting; how long I have too for that matter)

Like a bottle-imp toward a surface which can never be

approached,

Never pierced through into the timeless energy of a present

Which would have its own opinions on these matters,

Are an epistemological snapshot of the processes

That first mentioned your name at some crowded cocktail

Party long ago, and someone (not the person addressed)

Overheard it and carried that name around in his wallet

For years as the wallet crumbled and bills slid in

And out of it. I want that information very much today,

Can’t have it, and this makes me angry.

I shall use my anger to build a bridge like that

Of Avignon, on which people may dance for the feeling

Of dancing on a bridge. I shall at last see my complete face

Reflected not in the water but in the worn stone floor of my bridge.

I shall keep to myself.

I shall not repeat others’ comments about me.

The poem itself is an epistemological snapshot of its poet. Ashbery seems haunted by Shakespeare’s dark comedy Troilus and Cressida and by one exchange between Achilles and the dogfox Ulysses:

Achilles: What, are my deeds forgot?

Ulysses: Time hath, my lord, a wallet at his back

Wherein he puts alms for oblivion. . .

Reflections, streaming, ghostly transparency, drifting, prepare processes crumbling and sliding until the poet’s name threatens to be lost. Time the overhearer has a wallet at his back wherein he puts bills for oblivion. In my frequent phone conversations with John Ashbery, both of us knowing we will not meet again, I sometimes conclude by quoting to him the direct credo of the closing lines of “Wet Casements”:

I want that information very much today,

Can’t have it, and this makes me angry.

I shall use my anger to build a bridge like that

Of Avignon, on which people may dance for the feeling

Of dancing on a bridge. I shall at last see my complete face

Reflected not in the water but in the worn stone floor of my bridge.

I shall keep to myself.

I shall not repeat others’ comments about me.

For me this is haunting. A few nights back I had a singular nightmare in which I had walked too far and hailed a taxi to take me back to the Greenwich Village loft I am now forsaking. I had only a few coins for payment and was penalized by a grotesque incarceration. In the dream I recited this closing passage of Ashbery’s poem to placate the irate driver to no avail. I awoke bleakly and wondered whether I feared I never would see my complete face reflected in anything I could build. Ashbery’s glory is to have built an escape from narcissism into the haven of his constant readers.

Back to top

Mark Ford

I once joked to John that I often felt like a gambling man who kept betting on the same horse—him; fortunately for both of us, he kept on winning. I forget which prize or honor had just been awarded him, and which must have prompted the remark. I also once compared the hold of his poetry on those writing in his wake to that of Milton in the decades after the publication of Paradise Lost. Both comments elicited a wry, self-deprecating shrug. Deep sorrow at his passing can’t help but be mixed with grateful wonder at all he accomplished, at all he was.

Back to top

David Lehman

John was a genius. I believe you could come to this conclusion from his poems—or from spending half an hour with him. He was also the most amusing person, especially when he had a martini in him and could relax.

One evening in 1980 I visited him and he read me some of the poems in the new ms. that became Shadow Train. (Its original title was “Paradoxes and Oxymorons” but JA changed it because it was too similar to the title of a collection of Kafka pieces.) After John read a poem I said it was terrific. I said the same thing after the second poem. The third time the same. And again. “I like them all,” I said, worrying that I was not being sufficiently discriminating. “Maybe I’m not the right audience for you.” “No, you’re exactly the right audience for me.”

My friend Ricky Ray recalls that at Brooklyn College, Allen Ginsberg (“first thought, best thought”) asked John about how he wrote. Ashbery said, “Well, I start the line, and when it starts to make sense, I change the subject.”

Back to top

Adam Fitzgerald

For six or seven years, thanks to Deborah Landau, poet and director of NYU’s Creative Writing program, I was able to help chair talks every spring with John Ashbery and others regarding the inroads his poetry drew from and built with regard to the other arts as well as popular culture. Some of these conversations centered around impossibly large topics—collage, French cinema, the prose poem, contemporary classical music, translation, the baroque, “minor” art, etc. But we also were able to irrigate relationships John had had with specific artists over the span of his rich imaginative life: Raymond Roussel, Joseph Cornell, John Cage, Henry James, Proust, Max Ernst, Joe Brainard, among others. Scholars, young and old, also joined the talks to reflect on their collaborations and research over the years: from longtime friends and devoted readers (John Yau, Eugene Richie, Rosanne Wasserman, Eileen Myles, Robert Polito) to a younger generation of poets (Farnoosh Fathi, Emily Skillings, Marcella Durand, Ava Lehrer), most of whom had worked with him quite closely in recent years. In all of these crossings, it became apparent that John was our uncanny instigator, not just of what to engage, but how to engage it. (He dreaded the prospect of lecturing, but relished the chance to “anecdote” at us, often quite hilariously.) Once, I remember asking him flat out in the middle of a seminar just what allowed him to feel so comfortable in violating the received ideas of poetry, so assured for example that a sestina could be written with Popeye scratching his balls, that one could and should incorporate any aspect of lived life into the contour of a poem’s wonder (given the climate of Harvard in the 1940s and, well, all of America in the 1950s). He said, quite movingly, “I guess that was thanks to Frank O’Hara.” Webs of friends and art, books and lovers—experiences that he made as large as poetry itself—were what John gave us, the grand permission as it were, to fully embrace and play with the life of language, life through language. His thousands of poems are the veritable proof. Talk about an instruction manual. Thank you, JA.

Back to top

More on John Ashbery

Best American Poetry: Remembering John Ashbery

Guardian: Obituary by Mark Ford, editor of LOA’s Ashbery edition

Hyperallergic: Late Indulgences: John Ashbery’s Breezeway

LitHub: 90 Lines for John Ashbery’s 90th Birthday (originally published July 28, 2017)

Slate: John Ashbery’s Convex Mirror

Vulture: When John Ashbery Was New York’s Art Critic