John Quincy Adams began keeping a diary in 1779, when he was twelve years old, and faithfully maintained it until his death at the age of eighty, when he was serving as a member of Congress. From the American Revolution to the brink of the Civil War, Adams’s diaries vividly capture historical events in which he was both participant and observer, while simultaneously revealing the play of an unusually lively and inquiring mind.

|

Library of America is now making this extraordinary work available to a general audience in the first new edition in almost a century. Edited by historian David Waldstreicher and published just prior to Adams’s 250th birthday, on July 11, The Diaries of John Quincy Adams 1779–1848 is a two–volume reader’s edition based for the first time on Adams’s original manuscript diaries, including numerous personal passages that were suppressed from previous versions. An early review in the Christian Science Monitor called the set “spellbinding” and “an astonishing sustained performance.”

David Waldstreicher is Distinguished Professor of History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and the author of several works on early American history, including Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (2009); Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (2004); and In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820 (1997).

Below, Waldstreicher describes what was involved in preparing two volumes of Adams’s diaries for Library of America.

LOA: The diaries of John Quincy Adams total some 15,000 handwritten pages and span a period of nearly seventy years. What were the challenges in winnowing such a massive work into a manageable two-volume readers’ edition? What were your principles of selection?

Waldstreicher: LOA rightly encouraged me to focus on entries of the greatest literary, biographical, and historical interest. Fortunately, these criteria often overlapped: Adams often wrote to record major events and to reflect upon them.

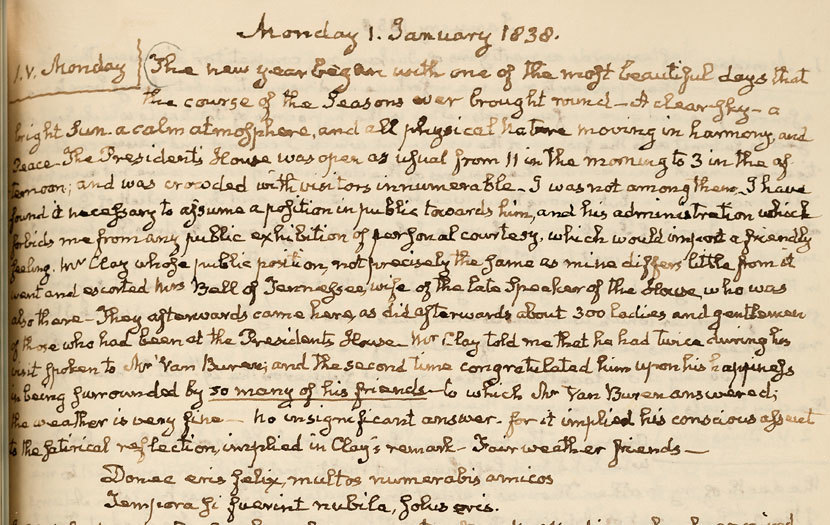

We had to be especially selective in the later years, when JQA began to write more than a large manuscript page (in the small handwriting that can be seen on the endpapers), and during those weeks and months when he was negotiating a treaty, or when Congress was in session. We had to edit in such a way as to avoid unnecessary repetition while making sure to represent JQA’s many varied concerns, like his commentaries on sermons he heard at church and his observations on mores at court in St. Petersburg.

LOA: Adams held enough positions for several lifetimes: minister to several European capitals, U.S. senator, professor at Harvard College, secretary of state, president, and finally congressman for the last seventeen years of his life. Did you consciously strive for a balance in representing all these phases of his career, or do the diaries favor some at the expense of others?

Waldstreicher: Adams was especially fulsome in the diary as a foreign minister in Russia, as secretary of state, and as a member of Congress, taking down the words of others and his reactions to them, for future use. There is not as much, perhaps surprisingly and perhaps not, during his frustrating presidential years, though it’s clear from the diary that he received many more visitors than he is given credit for as a supposedly “pre-democratic” president. We did strive for balance—and had to make painful cuts—but the high quality of the entries in which he gears himself up for battle with the leading lights of the age, or when he reflects on what he has seen and heard, are certainly well-represented.

LOA: The twelve–volume edition of the diaries prepared by Adams’s son, Charles Francis Adams, from 1874 to 1877 suppressed many entries dealing with John Quincy’s private and family life. To achieve a more rounded portrait, you’ve restored some of that material in this edition. What are some of the revelations in these passages?

Waldstreicher: Adams emerges in our edition as more engaged with members of his family, and with people generally, than in past editions that focused solely on political significance. Another revelation that might be less surprising to readers of the Charles Francis Adams edition is just how many of the celebrities of the age Adams interacted with substantially, and how passionate and informed he was about numerous literary genres, from sermons to plays to philosophy to poetry.

And there are nuggets that Charles Francis Adams, with his nineteenth–century eyes, just missed—such as Adams conferring with Prince Saunders, acting as an informant about Haiti, while Secretary of State. He has never been credited as the first president we know of to receive an African American (Reverend Richard Allen) in his office—that credit is usually given to Lincoln or Theodore Roosevelt.

LOA: One of the extraordinary features of Adams’s diaries is that in addition to participating in historic events he’s also a great noticer of them—he’s one of those, in Henry James’s phrase, “on whom nothing is lost.” Where did this ability come from? Did he consciously train himself to develop a recording faculty?

Waldstreicher: Part of it was his informal diplomatic training abroad, as his father’s secretary during his teenage years. Diplomats had to report on conversations and keep good records. JQA rapidly advanced in the diplomatic corps under Washington in part on the strength of his dispatches from Europe as well as his anonymously published opinion pieces in newspapers based on what he had seen and heard. John Adams also insisted on the great value of diary keeping, and John Quincy turned out to be even better at it than his father.

LOA: Adams’s views on slavery evolved over the years, to the point where as a congressman from Massachusetts he was the most vocal opponent of the “Slave Power” in the House. How much of that evolution is recorded in the diaries—are there turning points readers should look out for?

Waldstreicher: The diaries are an excellent place to see JQA’s evolution from someone who wanted to keep the slavery issue at bay, and in fact helped the National Republicans (the Madison and Monroe administrations) do just that, to becoming someone who wanted to highlight slavery’s importance in politics and its connection to so many other key issues facing the nation. The Missouri Crisis debates in 1819–21 are a key moment of realization, but we also see in the diary his commitment to avoid taking a public stand. The other key moment of transition comes after he leaves the presidency, when he explored in various writing projects his intensifying realization that the “Slave Power” had stymied not just antislavery but his policy agenda for the nation.

Subsequently, for the next decade and a half, he tried out different strategies and relationships to the changing antislavery movement in his diary, consistently reminding himself to keep a careful distance from immediate abolitionism even while developing a dialogue with key proponents like Benjamin Lundy and Theodore Dwight Weld. He did a great deal of effective work for the movement by discrediting slavery and its influence in national politics—the famous Amistad case is just a chapter in the middle of that story.

LOA: Joseph Ellis, an authority on the founding generation, recently wrote, “John Quincy Adams is easy to admire, but difficult to like, much less love.” Are people reading these diaries likely to come away with that impression as well?

Waldstreicher: Like many pronouncements about the Founders, this is an elegant and amusing half-truth that is more revealing about the genre of founder commentary than it is about John Quincy Adams. Adams was reserved yet a great conversationalist. He had his enemies, great admirers, and many friends. Like most politicians who were also writers, he was liked and loved—and despised—from afar and up close. The same might be said for Franklin, Madison, John Adams, and especially Jefferson—with whom Adams had a revealing love-hate relationship, which the volumes trace over many decades.

Watch a trailer for The Diaries of John Quincy Adams (1:48)