By Imogen Sara Smith

Tragedy is surprisingly faithful to Theodore Dreiser’s monumental 1925 novel, while Sun presents an enduring depiction of a dream of perfect love.

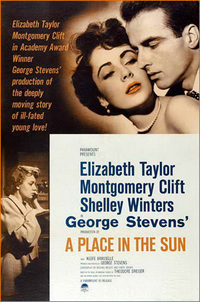

When you think of A Place in the Sun (1951), you probably think first of the kiss—that series of melting, shadowy, rapturous close-ups enveloping the screen when Montgomery Clift locks lips with Elizabeth Taylor. At once breathtakingly intimate and nearly abstract, the scene is an icon of cinematic romance, but the story behind it is a tortuous trail of adaptations leading back to an origin that’s anything but pretty.

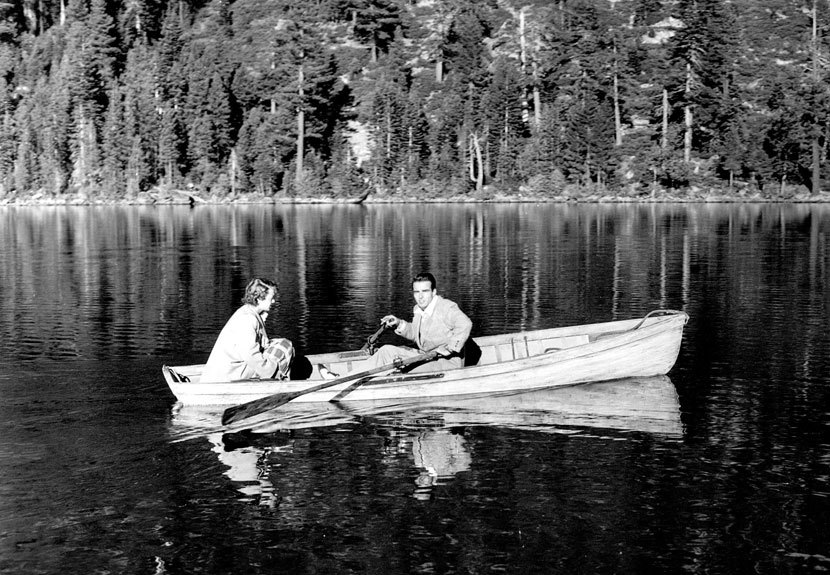

It all started in 1906 at Big Moose Lake in upstate New York, where a young man named Chester Gillette took his pregnant girlfriend, Grace Brown, out in a rowboat and drowned her. The two worked at a local garment factory, but Gillette had begun to move in higher social circles and hoped to marry a wealthy girl. Instead he went to the electric chair in 1908, following a trial that was a tabloid sensation. Theodore Dreiser transformed this sad, notorious murder case into An American Tragedy. He used it to illustrate how the overpowering lure of success and upward mobility could warp an average man and dazzle him into mistaking money and social acceptance for beauty and happiness. In Dreiser’s 1925 novel, Chester Gillette becomes Clyde Griffiths, a weak-willed young man raised in drab poverty made even more humiliating by his parents’ religious evangelism. A long introductory section (largely skipped by both film adaptations) follows Clyde through his first job as a bellhop in a large hotel and establishes his naïve, unformed, waffling character and his intense susceptibility to high life and, above all, to feminine beauty. Good-looking, eager, with a charming and malleable manner but no real talents or goals, Clyde is a tragic version of a 1920s stock character, the ambitious striver who rises from humble beginnings.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Theodore Dreiser: An American Tragedy |

Dreiser’s greatest accomplishment, in a very long book that at its worst can feel plodding and ponderous, is his commitment to ambiguity. He makes Clyde’s emotions so vivid that the reader cannot help but become involved in them, yet at the same time ruthlessly delineates a “temperament that was as fluid and unstable as water.” While Clyde’s behavior is increasingly despicable—he seduces the innocent factory girl Roberta Alden, then drops her when he’s taken up by the rich and lovely Sondra Finchley—he is so hapless and overmastered by his desires that he’s hardly responsible for his actions. When he first sees Sondra, “the effect on him was electric—thrilling—arousing in him a curiously stinging sense of what it was to want and not to have.” One’s ambivalence toward this protagonist is heightened by a profoundly ambiguous crime. Clyde plots to drown the pregnant Roberta to get out of marrying her, but at the crucial moment he can’t get up the nerve to do it; when the boat overturns accidentally, he consciously decides to abandon her, knowing she can’t swim. Readers, like Clyde himself, struggle to decide how guilty he really is.

Dreiser’s magnum opus won immediate acclaim. Hollywood was quick to snap up the story; Paramount bought the rights for $150,000 and even threw in a clause in the contract that gave Dreiser the right to view the script and made a vague promise to accept his suggestions—if the studio saw fit. In 1929 they assigned the project to Sergei Eisenstein, whose screenplay, unsurprisingly, emphasized the book’s social criticism, and used arty techniques like a stream-of-consciousness voice-over. The author was pleased, but the deal fell through, and producer Adolph Zukor turned to Josef von Sternberg—fresh from Morocco (1930) and at loose ends as Marlene Dietrich made a visit to Germany—and asked him to salvage the investment. In his memoir, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, Sternberg blithely says he “eliminated the sociological elements, which, in my opinion, were far from being responsible for the dramatic incident.” Dreiser was so disgusted by the new screenplay (written by Samuel Hoffenstein) that he unsuccessfully sued Paramount, claiming his novel had been “traduced” into a cheap, melodramatic potboiler.

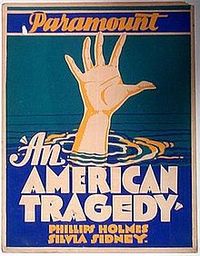

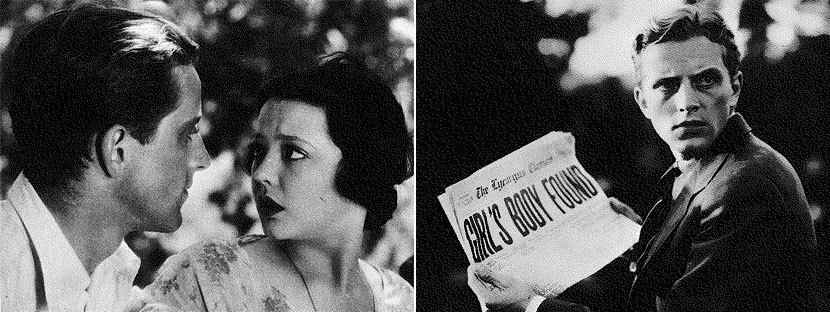

As Sternberg maliciously pointed out, Dreiser’s sputtering rage is hard to fathom, since the script, though inevitably truncated, follows the book almost slavishly, with many scenes, lines, and details drawn straight from the text. Sternberg’s An American Tragedy (1931) is more faithful to both the letter and the spirit of the novel than George Stevens’s better known A Place in the Sun (1951), and its take on the story is radically different. Beneath the shimmering luminosity that Sternberg and cinematographer Lee Garmes give to the film, there is a pre-Code toughness and astringency. Sternberg may have said that he jettisoned the sociological elements, but the film casts a jaundiced eye on rich and poor alike, casually exposing snobbery, corruption, and mob mentality. Dreiser’s frank treatment of sex was controversial for its time, and Sternberg plays up the hothouse atmosphere. As he moves from hotel to factory to debutante parties, Clyde (Phillips Holmes) is constantly surrounded by girls who make eyes and throw themselves in his path.

The emotional heart of this film lies with Roberta, thanks to the vulnerability and guileless charm of Sylvia Sidney. Typecast as poor, downtrodden girls, Sidney instilled these baby-faced waifs with her grit and sharp-edged smarts, and with the eye-scrunching sweetness of her smile. All this makes it hard to understand, much less forgive, Clyde’s murderous resentment of Roberta. Beautiful Frances Dee, as Sondra, is fittingly seductive and spoiled, but the character is hardly developed. And in the central role, Phillips Holmes fully embodies Clyde’s weakness, but is too much of a chilly blank to invite audience sympathy. With his blond, patrician handsomeness, Holmes had a brief run as a leading man in the early 1930s despite a pallid, neurasthenic look. (No sissy in real life, he died in a mid-air-collision during World War II after volunteering for the Royal Canadian Air Force.) Hollywood studios might be willing to build a movie around a charismatic anti-hero—like James Cagney’s Tom Powers in Public Enemy—but rarely did their films revolve around such an ineffectual weakling. The over-long trial scenes that dominate the last third of the film contain a jaw-dropping gambit in which Clyde’s lawyers mount a defense based on his being a “mental and moral coward,” arguing that he should not be punished for lacking the courage to save Roberta.

Though Sternberg largely dismissed An American Tragedy as an uninspired assignment, it has memorable elements. Liquid imagery flows through the film, from the elegant titles superimposed on clear water that shatters in ripples; through the breezy, dappled brightness of the riverside where Clyde first woos Roberta; to the quiet, pristine lake where we see her flounder and go under. Most striking is the scene just before Clyde is arrested. He and his wealthy, stylish friends glide aimlessly in canoes, singing the bluesy, minor-key “Some of These Days,” which sounds oddly menacing as it drifts over the water. If there was a mismatch between Sternberg’s sensibility and Dreiser’s (as David O. Selznick wrote in a memo that advised against giving the project to him), it is mostly to the good of the film. The strongest moments are the ones that feel uncomfortable and cryptic, like the creepy smile Clyde gives to his mother as he is sentenced to death.

Sternberg’s film got mixed reviews and flopped resoundingly at the box office, though it was enough of a cultural event that Groucho Marx could quip in Horse Feathers (1932), another Paramount film: “You know, this is the first time I’ve been out in a canoe since I saw An American Tragedy.” But in the late 1940s, when George Stevens began badgering Paramount to let him adapt the property, the studio executives stonewalled. Eventually the director followed Dreiser’s lead and sued the studio, which relented partly because he convinced them that casting Montgomery Clift in the lead would make the film appeal to young audiences. Stevens, who made his name in the thirties directing light comedies and women’s pictures, fastened on this story after he returned from leading a U.S. Army film unit throughout World War II. Deeply affected by the atrocities he had witnessed, including the liberation of Dachau, Stevens sought a substantial project that would capture his postwar mood. An American Tragedy offered a vehicle for the kind of scathing anatomy of American materialism and moral flimsiness that film noir was then dishing out. Curiously, however, Stevens began turning the dark material into something else: a love story.

While Stevens may have wanted to assure Paramount a hit, it also seems that he was tugged by some strong, if inchoate, emotional need to reshape the story. His take was starkly Manichean, and he stubbornly resisted objections from cast members and others that he was unbalancing the plot by creating the strongest possible contrast between the story’s two women. Where Sternberg cast a cold eye on Clyde Griffiths, Stevens loaded the dice in favor of the antihero he renamed George Eastman, making him a victim rather than a fumbling, would-be villain. Ultimately, the director’s emotional connection to the romance and the impassioned filmmaking it inspired give A Place in the Sun its power, outweighing the sometimes heavy-handed and over-determined storytelling.

The movie’s casting is its destiny. Montgomery Clift, the first choice to play George Eastman, had no illusions about the character, who, he told Robert Ryan, “has some charm, but basically he conceals and dissembles about everything. He’s tacky and not that bright, but he’s overwhelmingly ambitious.” Yet Clift’s radiant openness and painful sensitivity, the vulnerability telegraphed by his concave posture and nervous mannerisms—hitching up his shoulders, ducking his head—make it hard for the audience to take such a dim view of George. From the start, he is a romantic figure. Under the movie’s credits, we see a slender figure in a leather jacket hitchhiking on a dusty, wide-open western highway. He backs slowly toward the camera, then finally turns for a screen-filling star close-up, revealing Clift’s dark, angular, luminous-eyed beauty. The camera creeps even closer, as though it wants to kiss him, as he gazes upward with a rapt, dazzled, sexy hunger. Finally a reverse shot shows what he’s looking at: a huge billboard with a pinup girl in a swimsuit and the tag line, “It’s an Eastman!”

Stevens turns Dreiser’s collar factory, which symbolizes bourgeois respectability (any office-clerk can put on a starched collar and elevate his class standing), into a manufacturer of bathing suits. Cheesecake pictures hanging everywhere in the workplace underline the sex appeal of money—a clever visual device that nails the way, in the novel, Clyde always conflates youth, beauty, wealth, and class. But Dreiser complicates this equation by making Roberta, the poor factory girl, very pretty and physically attractive to Clyde, at least at first; the greater appeal of Sondra resides in her chic, tantalizing air of unattainable status. (Significantly, Clyde sleeps with Roberta but never contemplates pre-marital sex with Sondra.) Stevens, however, felt that the girl for whom George Eastman would kill had to be someone anyone in the audience would feel was worth killing for. The seventeen-year-old Elizabeth Taylor fit the bill. Costumed by Edith Head in strapless gowns that accentuate her flowering bosom and vanishingly small waist, and all but caressed by an infatuated camera, Taylor is ravishing beyond belief. More importantly, her character, renamed Angela Vickers, is not the vain, frivolous, baby-talking tease of the book. She is, for all her dewiness, forthright and kind, instantly drawn to an outsider. And Clift’s George, with his dangling cigarette and pool-table prowess, is much cooler than Clyde Griffiths was ever meant to be, signaling a rebel mystique beneath the character’s dog-like eagerness to belong. As they sway in a trance on a deserted dance floor, or cavort beside a sparkling mountain lake, or as she cradles him in a convertible at night, they easily embody Hollywood’s ideal of young love.

Paramount, sniffing a sure-fire way to sell the film, promoted a romance between Clift and Taylor, assigning him to escort her to the premiere of The Heiress (1949). “Their beauty together was staggering,” recalled actress Diana Lynn, who was at the party after the screening: “One could see her as goddess, mother, seductress, wife. One could see him as prince, saint, and madman.” From this phony beginning a true friendship would grow; even as a teenager, the besotted Taylor was mature enough to accept Clift’s homosexuality and understand his struggles with it. Their chemistry onscreen cannot but skew the story: the love of George and Angela is unquestionably the real thing. Who can argue with that?

For the role of the factory girl, here called Alice Tripp, Stevens first thought of Cathy O’Donnell, whose soft, sweet innocence would have been perfect. Barbara Bel Geddes wanted the part, but he felt she would have too much appeal. Clift pushed for Betsy Blair, who would prove to be so touching as the “plain” girl in Marty (1955). Shelley Winters, tired of being typecast as a blonde bombshell, landed the part by deglamorizing herself to the point that Stevens did not recognize her at an audition. She later rued the extent to which the director insisted on making Alice dowdy, coarse, and unsympathetic. Clift vehemently argued against this “downbeat, blubbery, irritating” performance, which seemed intended to make everyone in the audience root for George to dump Alice in the lake. But Stevens later said that what interested him most in the film was “an imbalance of images which created drama,” meaning the unkind cuts and dissolves that contrast the frumpy, whining Alice with the luscious, bewitching Angela. There is something positively punitive in the director’s treatment of Alice, whom he described as “the kind of girl a man could be all mixed up with in the dark, and wonder how the hell he got into it in the daylight.” That’s a pretty horrible thing to say, and he illustrates it by frequently shooting George and Alice in near-total blackness or in oddly obscured, distant setups that block our sympathy.

Not content with giving George every reason to drown Alice, Stevens goes even further and largely absolves him of guilt. Out on the lake, in an eerie twilight shivered by the cry of loons, Alice makes a dreary, soul-crushing speech about how George will eventually settle down and be content with “the little things” instead of yearning for what he can’t have. Upset by his angry reaction, she stands up and overturns the boat—and the camera then cuts to a distant view of the tiny splash disappearing in the tranquil, inky water. Stevens even shot footage, later cut, of George desperately trying to save Alice, as he insists he did in the courtroom—a stark contrast to the damning scene in which Sternberg showed us Clyde deliberately swimming away from Roberta. Further stacking the deck, Raymond Burr plays the D.A. who prosecutes George as a snarling, sinister adversary whose courtroom hysterics seem guaranteed to alienate a jury—and an audience. The film is full of such alterations, from a scene in which George impresses Angela’s father with his sincerity (thwarting the book’s implication that Clyde’s dream of marrying Sondra is a self-deluded fantasy) to Angela’s invented visit to the condemned George’s cell.

What then is A Place in the Sun about, if it is not about a morally bankrupt youth corrupted by the false glamour of the American dream? It’s about a greater, older, and more universal dream, the dream of a perfect love. Stevens seems intent, in the love scenes between Clift and Taylor, on outdoing anything yet achieved in romantic cinema. At 2:00 a.m. on the night before shooting, the director rewrote the key scene of their first kiss, transforming dialogue from the book (when Clyde says, “If I could only tell you all,” he is wishing he could confess to Sondra about Roberta) into a legendary exchange. “Forgive me, but what the hell is this?” Taylor asked when she was handed the new script pages; she felt the line “Tell mama, tell mama all,” was absurd, though she spoke it with tender, mesmerizing conviction. As the dark, blurred masses of Clift’s back, his hair, and her hair blot out parts of the frame, we don’t see their kiss but experience it, lost in their ecstasy. Stevens edited the shots so that their faces would seem to be dissolving into one another in a rhapsody of black and white. When this kiss appears again superimposed over George as he walks numbly to the electric chair, the film affirms that such love is worth killing or dying for.

If A Place in the Sun neglects An American Tragedy’s message of how people are shaped by social and economic forces, it stays true to Dreiser’s even darker pronouncement of the book’s meaning in his diary. “Life is made for the strong. There is no mercy in it for the weak—none,” he wrote. “Such is the tragedy of desire.” Clift’s George Eastman remains fatally passive and soft, full of yearning but unable to face the consequences of his actions, his “fluid and unstable” nature flowing like water that finds its own level.

Video: Original 1951 trailer for A Place in the Sun (2:43)

An American Tragedy (1931). Directed by Josef von Sternberg. Screenplay by Samuel Hoffenstein, based on the novel by Theodore Dreiser. With Phillips Holmes, Sylvia Sidney, Frances Dee, Irving Pichel, Lucille La Verne.

Buy the DVD

A Place in the Sun (1951). Directed by George Stevens. Screenplay by Michael Wilson and Harry Brown, based on the novel An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser, and the play by Patrick Kearney. With Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, Shelley Winters, Raymond Burr, Anne Revere.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy. She writes regularly for The Criterion Collection, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, and other publications.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.