In honor of Library of America’s new Carson McCullers collection Stories, Plays & Other Writings and the McCullers centennial on February 19, 2017, poet Nick Norwood contributes an Influences column expressing his personal connection to McCullers and her work. Norwood is Director of the Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians in Columbus, Georgia, and Nyack, New York.

It’s the most overlooked thematic thread in McCullers’s work—the misery of the working class. She has been important to us for her explorations of loneliness: “An American Malady” she calls it in a short piece collected in the new Library of America volume Stories, Plays & Other Writings. And her treatments of race, sexual orientation, the need to connect, “to feel a part of life,” are, among other things, ways she explored that loneliness, different angles she took on it.

But being poor is another, and having grown up in a cotton mill town like Columbus, Georgia, McCullers knew firsthand what poverty looked like. It affected her deeply. Millworkers serve as her example of folk beaten down by economic forces larger than themselves. “These cotton mills were big and flourishing,” the narrator of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter says in describing the largest employers of the novel’s fictional town, “and most of the workers in the town were very poor. Often in the faces along the streets there was the desperate look of hunger and of loneliness.”

In the “Author’s Outline of ‘The Mute’ [her working title for The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter],” which McCullers submitted to a fiction contest sponsored by Houghton Mifflin and is also reprinted in the new LOA volume, she both displays her firsthand knowledge of the millworkers’ plight and demonstrates that she had done her homework on mill culture elsewhere in the South:

The town is located in the very western part of Georgia, bordering the Chattahoochee River and just across the boundary line from Alabama. The population of the town is around 40,000—and about one third of the people in the town are Negroes. This is a typical factory community and nearly all of the business set-up centers around the textile mills and small retail stores.Industrial organization has made no headway at all among the workers in the town. Conditions of great poverty prevail. The average cotton mill worker is unlike the miner or a worker in the automobile industry—south of Gastonia, S.C., the average cotton mill worker has been conditioned to a very apathetic, listless state. For the most part he makes no effort to determine the causes of poverty and unemployment. His immediate resentment is directed toward the only social group beneath him—the Negro. When the mills are slack this town is veritably a place of lost and hungry people.

Another important revelation of McCullers’s description of the mill culture is, of course, its effect on race relations. Surely it would be unfair to lay all the blame for the South’s racial tension on the mill economy. On the other hand, as McCullers points out, the way the mills tended to enforce a rigid class structure only made the situation worse.

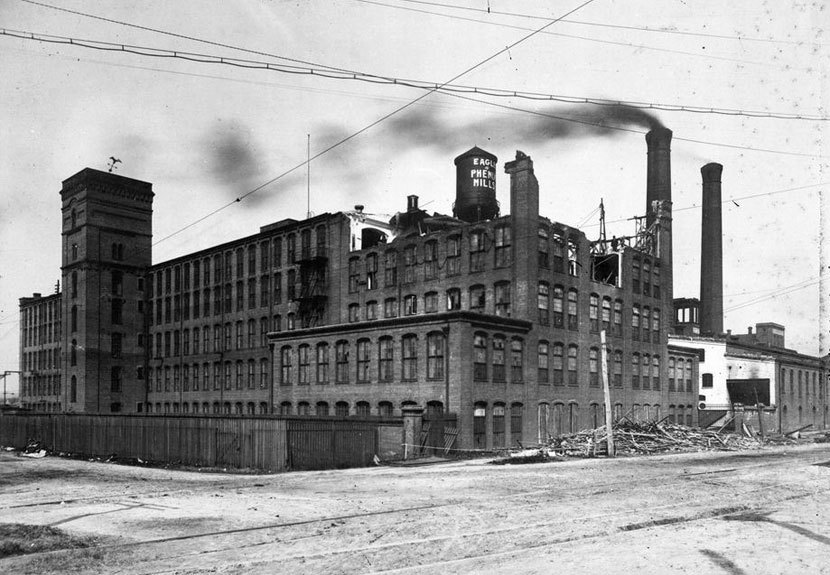

I now live in the largest of those Columbus cotton mills, The Eagle & Phenix, converted into condos by the same company that ran it as a mill for over a century. And living here has inspired me to extend the work I began in my last volume of poems, Gravel and Hawk (2012), in which I focused on the lives of my family in East Texas who were tenant cotton farmers and thus belonged to the same cultural-socio-economic group that went to work in the mills. Poor crackers like my grandparents, who were married in 1930, left the uncertain misery and poverty of the cotton farm for the certain misery and poverty of the cotton mill. The difference with my grandparents was that they stayed on the farm—a wise choice, I think. But I can easily see them working in the mills. The workers in the images of Lewis Hine, for instance, look exactly like my people in East Texas. They could be my cousins, and in some cases, I’m sure they were.

In working on my new book of poems I have read as much about the mill culture as possible, have visited history and cotton mill museums here in Columbus, in Lowell, Massachusetts, and in Manchester, England. One of the most striking images of that milieu has come from McCullers, in a piece called “The Great Eaters of Georgia,” also collected in the new LOA volume. In early 1954, reflecting on a recent visit to her hometown, she says, “There are still slums in Columbus, but I was not struck by the brutal poverty that had oppressed me when I saw it years ago. I remember being with my grandmother once, when I was a child, in a Christmas visit to the mill section, and I saw a baby sitting on a chamber pot by an open front door in a cold two-room house with only a puny blaze in the fireplace. The degradation and desolation of that single scene has never left me although it is more than twenty years ago.”

I’m like a lot of McCullers admirers in that there was something in her work that made a connection with me, to my own past and experience. I think her sympathy for working people—from Jake Blount in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter to Berenice Sadie Brown in The Member of the Wedding—is the aspect of her work that has perhaps most influenced my own.

Nick Norwood is a professor of creative writing at Columbus State University and Director of the Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians in Columbus, Georgia, and Nyack, New York. He is the author of three volumes of poems, the most recent of which, Gravel and Hawk (2012), won the Hollis Summers Prize in Poetry from Ohio University Press. His writing has been published in The Paris Review, Southwest Review, Western Humanities Review, Shenandoah, The Oxford American, Tar River Poetry, The Texas Review, and Copper Nickel, among numerous other magazines and anthologies.