By Terrence Rafferty

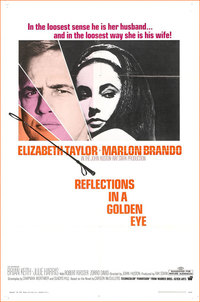

Nothing human was alien to Carson McCullers, and in 1967 her work found ideal interpreters in the “superb reader” John Huston, a fearless Elizabeth Taylor, and Marlon Brando, whose philosophy of acting matched her philosophy of writing.

Sometimes when Carson McCullers talked about writing she sounded like an actor.

“When I write about a thief,” she once said, “I become one; when I write about Captain Penderton, I become a homosexual man; when I write about a deaf mute, I become dumb during the time of the story. I become the characters I write about and I bless the Latin poet Terence who said, ‘Nothing human is alien to me.’” Twenty years earlier, in 1939, she had dreamed up the sad story of repressed Captain Weldon Penderton and written it in a rush; according to her biographer, Virginia Spencer Carr, she polished it off in a couple of months. She first called her short novel Army Post, and then, a little less drably, Reflections in a Golden Eye. “An army post in peacetime is a dull place,” it begins, but only a few sentences later, in the same calm tone, it tells us: “There is a fort in the South where a few years ago a murder was committed.” And then, “The participants of this tragedy were: two officers, a soldier, two women, a Filipino, and a horse.” These are the dramatis personae, the characters she’ll become. Even the horse.

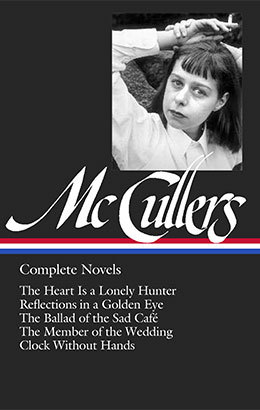

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Carson McCullers: Complete Novels |

Her audacity is wondrous. When she began Army Post, McCullers was all of twenty-two years old, a sickly young woman from Georgia who had already been married for two years and had already written a novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, that had been accepted by a major publisher. She was living and writing at fantastic speed, as if she knew her time would be short. Why not, she must have thought, write down this strange, upsetting story that had come to her, this hothouse tale of twisted desire and simmering violence? Why not become, for a while, these lost, unpleasant, desperately unhappy people? Captain Penderton is perhaps the most tormented and the most pathetic of them, despised by his wife, Leonora, and mooning over a quiet and unworldly enlisted man named Elgee Williams. But Private Williams is himself a pretty forlorn specimen of humanity, a country boy, unsocialized as a new-born puppy, whose first glimpse of a naked woman—Leonora—drives him to some mighty creepy, obsessive behavior; he takes to slipping into her bedroom at night to watch her sleep. (The captain, who has no interest in the voluptuous flesh that transfixes Private Williams, is never there.) And rivaling the two men in misery is the Pendertons’ neighbor Allison, who is married to Leonora’s lover, Major Morris Langdon. She’s frail, neurasthenic, and too sensitive; once, in a bout of depression, she cut off her nipples with garden shears. The only person she feels comfortable with is the Langdons’ gay Filipino houseboy, Anacleto, who dotes on her and entertains her with arty fantasies.

Fey Anacleto is certainly the most cheerful of the characters McCullers chooses to become in Reflections in a Golden Eye. (He’s also the least convincing.) Leonora and Morris don’t exactly glow with satisfaction, but they’re protected from despair by a shared dimness of imagination; they’re not introspective enough to recognize how lousy their lives are. It’s no wonder the interactions of these damaged people end in murder. The miracle is that McCullers, inhabiting them all like a Method actor, survived the writing of them.

Reflections in a Golden Eye didn’t find much favor with the critics and the readers of the time, either when it was serialized in Harper’s Bazaar in 1940 or when it was published as a book the following year, and it was, to say the least, not the sort of story that would have attracted the attention of Hollywood. (Good thing, too; the Production Code would have ripped out its soul.) In the ’50s, though, Burt Lancaster’s production company flirted with the idea of adapting it to the screen, with Tennessee Williams as screenwriter and Carol Reed as director. Nothing happened. A few years later, John Huston became interested, and roped in Elizabeth Taylor, then arguably the biggest star in the movie world, to play Leonora. Montgomery Clift, Richard Burton, and Lee Marvin (!) are said to have been considered, at various points, for Penderton but fortunately the part went to Marlon Brando, whose philosophy of acting was an ideal fit for McCullers’s philosophy of writing. For Brando, Huston wrote, “you simply have to be the character you’re supposed to be.”

The libidinous ’60s seemed the right time, finally, for Reflections in a Golden Eye. Huston was the right director, a superb reader who was, besides, entirely undaunted by works of literature others thought “difficult” or “unfilmable.” (He’d already tackled Moby–Dick and the Bible, and would later take a crack at Wise Blood, Under the Volcano, and “The Dead.”) He picked the right Leonora in Elizabeth Taylor, who was fearless in her own way. Unlike many actors who had come up through the old Hollywood studio system, Taylor was never intimidated either by the moody, intellectual-seeming Method guys—she had held her own, and then some, with Clift, James Dean, and Paul Newman—or classically trained Brits like her husband, Burton. She always gave as good as she got, and appeared to be enjoying the contest. Taylor puts both her combativeness and her unabashed sensuality to splendid use in Reflections in a Golden Eye. The Pendertons’ marital battles are unusually vivid and harrowing, in part because Taylor grounds Leonora’s anger at her husband’s indifference in the character’s Southern-belle sense of sexual entitlement: How dare he not desire her? And her ripe womanliness is, in a way, the pivot of the whole grim story: Looking at Taylor—riding her horse, undressing for bed, or just sashaying through a large crowd at a party—you understand perfectly why Leonora would fascinate a man like Elgee Williams and scare the hell out of a man like Weldon Penderton.

The movie has (mostly) the right supporting cast, too. Robert Forster, in his first movie role, plays the lovestruck private with the precise mixture of innocence and ominousness the part requires, and Julie Harris’s customary delicate-but-firm readings as Allison give the character—who might have been played for pure pathos—an unexpected reserve of strength. Alone among the self-absorbed folks on the base, she takes the trouble to pronounce Anacleto’s name properly, and you admire her for it. (Zorro David, as Anacleto, is bad, but the role is close to unplayable, and David wasn’t a professional: this was his first, and last, appearance on screen.) Brian Keith, as Major Langdon, has the burden of portraying the only character with whom a “normal” audience might conceivably identify, a dull, kind man who simply doesn’t want there to be so much trouble in his world, and Keith gets remarkable mileage out of the major’s varied—but constant—look of faint puzzlement. And when, near the end, some of the seldom-used rooms in Langdon’s brain begin to light up with a disturbing truth or two, Keith is extraordinarily moving.

To say that Brando is the right Weldon Penderton would be a grievous understatement. Huston had to talk him into taking the role, and the actor, whose commitment to his art had a tendency to waver, was coming off a couple of the least satisfying experiences of his movie career: a dud western called The Appaloosa and Charles Chaplin’s stillborn romantic comedy A Countess from Hong Kong. After Chaplin—whose filmmaking technique was, to put it mildly, not amenable to the kind of spontaneity that brings out the best in actors like Brando—Huston, who liked and trusted actors and let them discover their characters with minimal interference, must have been a huge relief. Julie Harris, Method-trained as Brando was, remembered: “He was taking the role seriously, almost as if he was exploring his own sexuality, or his own inner torment.” It’s not as if he hadn’t done that before, or wouldn’t do it again. Reflections in a Golden Eye is the middle panel of Brando’s great triptych of male sexuality, between A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Last Tango in Paris (1972). This performance is much less well-known than the other two, but I think it’s their equal.

Our first look at Brando here is startling. He’s pudgy and pasty-looking, sweating copiously as he works out with a barbell. This isn’t exactly Stanley Kowalski—earthy, swaggering, proud of his virility—though you sense that that’s what Penderton would like to be. (In his distraction and self-delusion, he’s actually closer to Blanche Du Bois; Leonora, who likes to taunt him, is Stanley here.) After the workout, panting, he checks himself out in the mirror, hoping in vain to see a transformation. It’s the first of several scenes in Reflections in a Golden Eye in which Penderton seems to be rehearsing another self: a part in a play for which he is the only audience. In almost all of Brando’s best moments in the picture, he’s alone on the screen. In a second mirror scene, the captain, in full uniform this time, practices the witty remarks and coy smiles he thinks he’ll need for a social occasion. In another, we see him applying cold cream to his aging face, pensively, rather sorrowfully. He spends many of his idle hours in his home office, dreaming on little treasures or beefcake photos. These queasy, heartbreaking vignettes don’t advance the story a bit, but they’re beautiful in themselves and they actually deepen McCullers’s conception of the character. In the novel, Penderton sometimes seems primarily a figure of fun, an object of ridicule. (She thought of it as a comedy.) As Brando plays the character, though, he is always at least a little more than that, and at times even approaches the grandeur of a (very unlikely) tragic hero. Watching Brando, you begin to appreciate what hard work repression is: how unremitting the pressure to maintain the ill-fitting facade, how much sheer vigilance it takes, day in and day out, to keep the fictional self from cracking in a thousand pieces. The movies have rarely shown a character so uneasy in his own skin, so thoroughly alienated from his physical being. If Brando’s Stanley Kowalski was a terrifying portrayal of a natural man, his Weldon Penderton is a fine-grained rendering of the most unnatural man in the world, and it’s no less frightening.

As it happens, the ’60s were no more the right time for Reflections in a Golden Eye than the early ’40s were. The story may be too peculiar for any time. The swingers of 1967, less prudish than the previous generation, still found McCullers’s people too weird, freaky in all the wrong ways. And the movie, besides, had an unusual visual style. Huston and his cinematographer, Aldo Tonti, worked with the Technicolor lab to produce prints in what the director called “a diffuse amber color,” which has the effect of distancing us further from the characters’ odd behavior: The awful goings-on have the incongruous glow of nostalgia. (After the film’s sparsely attended first run, the studio replaced the “golden” prints with ones in standard Technicolor.) The reviews were dismissive. Huston believed, to the end of his life, that it was one of his best movies. McCullers liked the script, by Chapman Mortimer and Gladys Hill, which was faithful to her idiosyncratic vision, but she died before Huston could show her the film he’d made. She was fifty years old.

In her final year, though, she traveled to the director’s home in Ireland, a visit she described—in an autobiography she wouldn’t live to finish—as “one of the happiest times of my life.” She came and went in an ambulance and spent all her time there in a hospital bed, looking “half doll, half mouse” to Huston’s teenaged daughter Anjelica, who later wrote (in her fine 2013 memoir A Story Lately Told), that “she absorbed us with enormous eyes, like blotting paper.” That was what Carson McCullers did, in her brief life and her fiction, absorbed the people she met as an actor does. Her mind’s eye was filled with them, and none of them were alien. It’s a shame she never got to see what Huston and Brando and Taylor and the rest had done with her story. They wrote it on screen for her, with their faces and their voices and their bodies. For once, she didn’t have to play all the parts herself.

Watch: 1967 trailer for Reflections in a Golden Eye (2:40)

Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). Directed by John Huston. Screenplay by Chapman Mortimer and Gladys Hill, from the novel by Carson McCullers. With Marlon Brando, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Harris, Brian Keith, and Robert Forster.

Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu • Watch on YouTube

Terrence Rafferty is the author of The Thing Happens: Ten Years of Writing about the Movies. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Times and The Atlantic.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.